Technological Adaptability: Why Averages Can Hide the Real Crisis

Published

Modified

Technological adaptability differs sharply across individuals, making averages misleading Social and economic factors determine who can realistically reskill Policy must target adaptability gaps, not average exposure

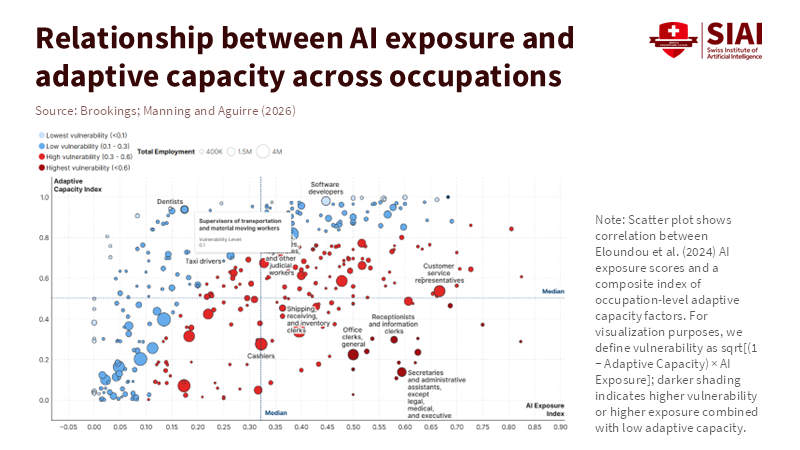

When analyzing the U.S. workforce's preparedness for artificial intelligence, research sometimes presents a misleadingly optimistic view. For example, one study measured AI exposure alongside the capacity to adapt. The results suggested that many workers at risk from AI can adjust to new roles. This may create a false sense that most workers are well-equipped for this transition. Averages smooth out the extreme differences. The ability to learn, change careers, and use new technologies isn't consistent across the population. It is greatly influenced by factors such as intelligence, age, education, language, financial stability, family responsibilities, and prior experience with technology. When we consider individuals, the averages should serve as a warning. The claim that most can adapt masks the fact that millions of people may find adapting difficult or unrealistic.

Technological Adaptability: The Danger of Averages

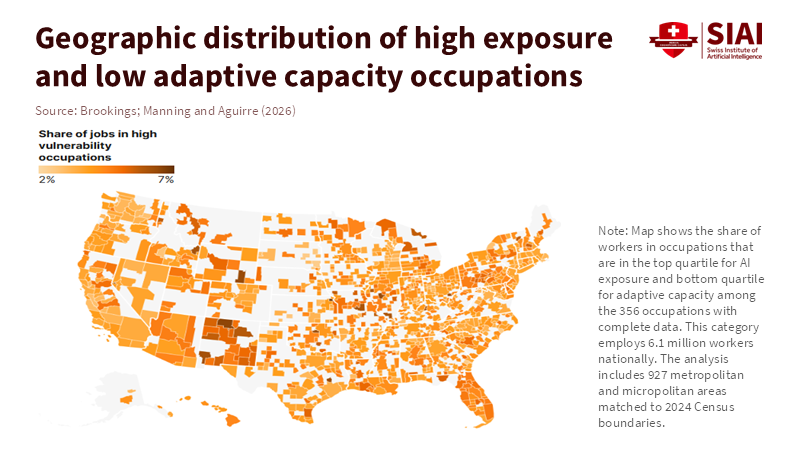

The problem is urgent: relying on averages conceals the wide range of abilities. Policymakers who trust average adaptation capacity may dangerously misestimate how prepared most people are. Averages can be skewed upward by those quickly adopting AI, while millions fall dangerously behind. These include older workers, those with less education, and those in rural or low-wage jobs. When analyses look at job-level ability, the situation appears far more critical. Policymakers must confront these differences now, with urgency, not complacency.

Consider the data on digital skills, a key element of adaptability. In the EU in 2023, only about 56% of adults (ages 16–74) had basic digital skills. This was 80% for those with higher education, but only 34% for those with little or no education. This 46-point gap is major. Similar patterns appear in OECD data. Digital divides correlate with age, income, and education. These same factors also predict who will struggle to change careers or learn to use AI tools in the workplace. Any average that doesn't account for these divides will overestimate how many people can adapt without help.

Labor market data support this point. Studies from the OECD and McKinsey show that automation and AI are impacting many industries and skill levels. However, the ability to retrain tends to be concentrated among those with higher education and those at larger companies with training programs. The OECD says that some jobs are changing in terms of required skills, not being eliminated completely. These new demands favor management, digital skills, and problem-solving. All of these skills are more common among those who already have access to education and training. Where few adults participate in lifelong learning, those most impacted by these technologies are the least likely to get retrained. In short, being affected by technology and adapting to it are not the same. The gap between the two is closely tied to existing inequalities.

Technological Adaptability and the Unequal Opportunity to Retrain

The pace of change demands immediate attention. Companies may adopt AI swiftly, but public training programs lag dangerously behind. Numerous reports warn of the massive, urgent need for workers to switch careers or gain new skills. Yet ability is consistently confused with access. When job losses happen quickly, only those with resources—savings, flexible schedules, childcare, and local training—can adapt in time. Others will be left behind, facing longer unemployment, plummeting earnings, and worsening job losses concentrated among the vulnerable. Policymakers must treat technological adaptability as a national emergency—delay will cost lives and livelihoods.

The numbers show this mismatch through looking at adult learning. In Europe, the rate of adults participating in learning was below 40% in recent years. These rates differ greatly across countries and social groups. We cannot assume that people can adapt to technology without targeted programs. Reports show that increasing general training will only worsen inequality if we don't address who is participating. Adults with more education benefit more from the same training opportunities. This explains why averages can be misleading: training and its benefits tend to be concentrated among those who are already better off, thereby misrepresenting the ability of the wider population.

Age and mental load can also change the capability to adapt. Older workers may find it harder to learn new digital skills. They may have less time to retrain because of family or health responsibilities. Language is also important. People who do not speak the dominant language may understand and learn more slowly if training and tools are primarily offered in that language. Those from wealthier origins often have advantages that help. They include savings that serve as a financial safety net, local networks, and sometimes awareness of different cultures. All of these factors impact how easily a person can adapt. The average can't accurately show that distribution. Evidence shows that the same issues appear across multiple studies.

Changing Education for Technological Adaptability

If adaptability varies from person to person, policies must be personalized as well. We need to shift from focusing on general numbers to diagnosing individual needs and creating specific plans.

Here are three things we should do:

First, assess each worker’s adaptability with practical tools that measure skills in technology, language, caregiving, and local job needs. Second, ensure free training and credentials, especially for those who score lowest in these assessments, and provide paid leave so they can participate. Third, combine training with direct financial aid and job placement support, helping workers complete training without losing income. Evidence supports that this approach leads to better outcomes.

To make this work, we also need to rethink how we prepare students for the workforce. Schools should teach how to learn, evaluate information, and adapt to new tasks. Attitudes are important. Those who are worse off may have less motivation to learn on their own. This can be addressed with early support and mentoring. Education should encourage lifelong learning so that adapting to new technology becomes a normal part of life. Otherwise, retraining will be a struggle for those who have the least means to do so.

Some argue that employers should provide most of the training needed. This idea is true when employers value their workers for the long term and when companies are large and have resources. But many workers are in small firms, temporary jobs, and positions with high turnover. In these positions, employer-provided training is limited. Studies show that employer training is inconsistent. Smaller businesses and their workers are left behind. Public policy must provide a backup plan through subsidies, training vouchers, results-based tax incentives, and training hubs in underserved areas. The goal is not to replace employer training, but to ensure everyone has the basics to adapt.

AI hasn't yet caused mass unemployment. Studies suggest AI hasn’t resulted in net job loss. AI's effects have been uneven, often changing tasks rather than eliminating positions. However, this does not mean we should delay action. The absence of job losses now doesn't change the fact that we don't all have an equal possibility to benefit from task changes. Some workers who learn how to work with AI will see higher wages, while those who can't will see their wages stop growing. Waiting until displacement happens will be more costly and less helpful. A careful equity focus is both prudent and wise economically and socially.

Finally, local factors are important. The ability to adapt to technology depends on the local job market. If training programs are for jobs that don't exist locally, people who complete the training will not get hired. Successful regional efforts connect training to employer needs, create apprenticeships, and invest in technology infrastructure in areas where it is lacking. This means moving funds from national campaigns to local training systems. These systems should involve employer groups, community colleges, and social services that collaborate jointly to achieve a common goal. These ecosystems can customize language, schedules, and content to local needs. Evidence suggests they lead to better job placement and retention than national programs that are not designed for regional factors.

Make Adaptability the Goal of Policy

Remember: averages cannot mask the real and immediate stakes as technological adaptability diverges dramatically. There is no time to let averages overshadow the urgent needs of those at the bottom. Policymakers and educators can no longer view adaptation as a side issue—it is a public emergency. Act now: measure individual needs, provide financial support for the vulnerable, and tie training to income and job placement. Hand retraining power to local entities. Only by moving swiftly can we prevent mass displacement and extend the gains from automation and AI. Translating numbers into urgent policy requires recognizing and measuring real needs and acting now to correct today's dangerous inequalities. The time to act is now: adaptability can no longer wait.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

McKinsey Global Institute. (2024). A new future of work: The race to deploy AI and raise skills. McKinsey & Company.

OECD. (2023). Skills Outlook 2023. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2024). Artificial intelligence and the changing demand for skills in the labour market. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2024). Who will be the workers most affected by AI? OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2024). Digital Economy Outlook 2024. OECD Publishing.

Eurostat. (2024). Skills for the digital age. European Commission.

Brookings Institution. (2026). Measuring U.S. workers’ capacity to adapt to AI-driven job displacement.

World Bank. (2024). Digital Skills Development.

Yale University & Brookings Institution. (2025). Study on AI and labor market outcomes. Financial Times coverage.

Comment