[HAIP] When Soft Law Meets Strategic Competition: Can HAIP Survive Geopolitical Divergence?

Published

Modified

HAIP faces pressure as national AI governance models increasingly diverge China’s state-led approach changes the incentives for voluntary global standards Without economic rewards, HAIP risks losing durability in strategic competition

By late 2025, more than fifty countries had joined the Hiroshima AI Process Friends Group, but the OECD platform listed fewer than thirty public HAIP reports. Meanwhile, China accelerated its AI governance plan, connecting AI oversight to industrial policy, security reviews, and platform registration. This highlights a key tension: HAIP tries to build agreement through openness, while China’s approach centers on growth through state control. When openness and speed compete, openness often loses. This leads to a political-economy problem: countries that cooperate pay a price, while those with looser rules gain market and technological advantages. The main question is whether HAIP can stay relevant as strategic competition changes the incentives.

Divergence is no longer just an idea

At first, global AI governance focused on shared language and principles. By 2025, the differences between models became clear and practical. The EU chose binding, risk-based regulations. The US used a mix of voluntary standards, security measures, and sector-specific guidance. Japan promoted HAIP as a flexible bridge between systems. In contrast, China expanded algorithm registration, security checks, content controls, and platform rules, linking governance directly to its industrial and national goals instead of focusing on voluntary openness. These approaches are not just different in style; they are fundamentally different in how countries expect to benefit—whether through legitimacy and openness, or through operational advantages from state involvement.

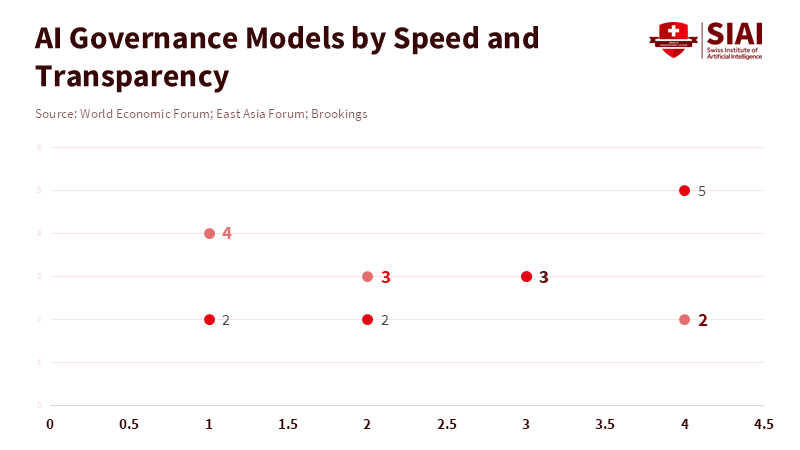

A World Economic Forum analysis in late 2025 showed that national AI governance models now balance innovation, trust, and authority in different ways. According to the OECD, the Hiroshima AI Process (HAIP) is meant to help stakeholders work together to promote safe, secure, and trustworthy AI, but it does not require enforceable rules. This cooperative approach helps with diplomacy, but it can be less effective in the face of international competition. Collaboration helps with alignment, but it does not prevent countries from taking advantage or using regulatory gaps. As differences affect market access, procurement, and government support, voluntary openness is at a disadvantage because it relies on reputation in a world where speed, scale, and state support matter more.

This is why educators and leaders should pay attention to these differences. Governance is not just about safety; it also shapes how countries compete. Since governance affects innovation, it influences where companies invest, where talent goes, and how fast new models are used. Flexible frameworks need to compete on both legitimacy and economic value. If not, countries may only join in occasionally or just for appearances.

China’s model changes the game

China’s updated AI governance plan shifts from fragmented rules to a more complete, state-led system. A late 2025 East Asia Forum analysis called this a phased approach that values flexibility and alignment over early rules. AI governance in China is closely tied to platform management, security reviews, and pilot programs that accelerate adoption while maintaining central control. The system isn't necessarily easier; it's just structured differently. It prioritizes speed, as long as it stays within state limits.

From a game-theory perspective, this difference is key. HAIP asks companies to report openly, share their processes, and go through peer review, using reputation and transparency as incentives. In contrast, China’s system requires companies to meet state goals and pass security checks to get faster market access, resource support, and coordinated rollout. These are different choices: one rewards openness and reputation, the other rewards following state rules and fast growth. As a result, companies might choose openness in HAIP markets but focus on speed and state support in others.

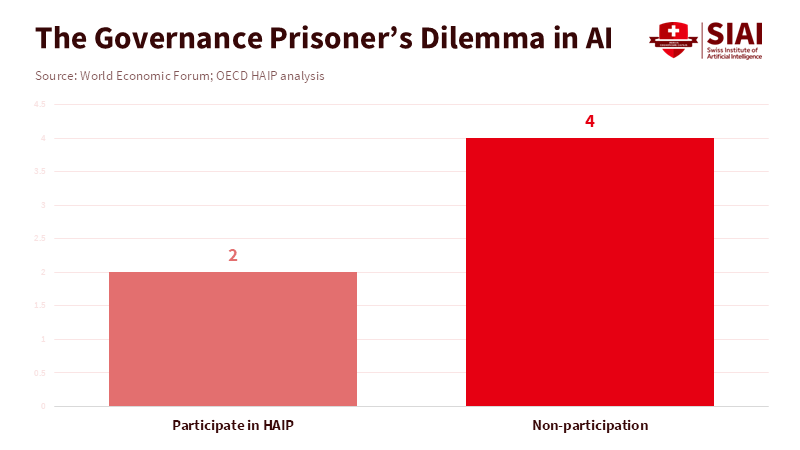

The real risk is not only that China could outpace others in governance, but that global standards could break down. If companies find that HAIP reporting does not help them commercially, while other systems offer more growth and speed, they may see HAIP as a waste of effort. This could undermine the cooperation that flexible rules depend on. It’s similar to a prisoner's dilemma: if others stop cooperating, the best choice is to do the same, even though everyone would benefit more from working together for safety and trust.

The prisoner’s dilemma for G7 governance

The G7’s challenge is not to copy China’s model, but to ensure HAIP sets a clear limit rather than just a starting point. The cooperative approach must bring real benefits. If not, countries will move to systems that offer better rewards, like easier market access, procurement advantages, insurance benefits, or fewer overlapping rules. Without these incentives, HAIP may exist only for show while real governance occurs elsewhere. Early HAIP participation highlights a real concern: there is strong support in principle, but less action. The small number of public reports is not because HAIP is rejected, but because companies are weighing the costs and benefits. Companies share only when it helps them, which is normal in a competitive world.

For leaders, this means HAIP cannot rely only on reputation. It needs to offer real economic benefits. Procurement rules, funding, and international agreements should be tied to verified reporting. Without these incentives, HAIP becomes optional, while competitors use governance as a tool for the industry. The G7 cannot succeed by appealing to norms alone; it must adjust the incentives.

What it would take to last

For HAIP to last, openness must be a core part of the system. This takes three steps. First, G7 procurement groups should accept each other’s HAIP reports to make things smoother. If a company has a strong HAIP report, buyers should act more quickly. Second, public funding and research should depend on the quality of governance. This makes reporting necessary for key partnerships. Third, there should be different levels of review: high-risk systems get expert checks, while low-risk systems have simpler reporting.

These steps aren't about punishing those who don't participate, but about making cooperation appealing. They increase the benefits of cooperating and reduce the temptation to go it alone. They also balance models that trade openness for speed. Importantly, they keep HAIP flexible while giving it strength through markets, not mandates.

For educators and leaders, this is important. It’s not enough to teach governance as just ethics; it must be taught as a strategy. Students should learn to assess incentive structures, not just principles. HAIP is a real example of how flexible law interacts with hard competition. Using it in this way will prepare future leaders to create systems that can survive in challenging environments.

HAIP was designed for a world where agreement through openness seemed possible. By 2025, governance will have also become a tool for competition. China’s different model and the slow adoption of voluntary reporting pose a risk: cooperative frameworks weaken when cooperation is costly and acting alone is rewarded. This does not mean HAIP will fail, but it does need to change. Openness must bring real economic and institutional benefits. Reviews must be fair and reliable. Procurement and funding should reward those who take part. Without these changes, HAIP could become little more than a symbol in a divided system. With them, it can still serve as a useful bridge. The real choice is not between flexible and strict law, but between flexible law with incentives and flexible law without them. Only the first can survive strategic competition.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Brookings Institution. 2026. “The HAIP Reporting Framework: Its value in global AI governance and recommendations for the future.” Brookings.

East Asia Forum. 2025. “China resets the path to comprehensive AI governance.” East Asia Forum, December 25, 2025.

OECD. 2025. “Launch of the Hiroshima AI Process Reporting Framework.” OECD.

World Economic Forum. 2025. “Diverging paths to AI governance: how the Hiroshima AI Process offers common ground.” World Economic Forum, December 10, 2025.

Ema, A.; Kudo, F.; Iida, Y.; Jitsuzumi, T. 2025. “Japan’s Hiroshima AI Process: A Third Way in Global AI Governance.” Handbook on the Global Governance of AI (forthcoming).

Comment