Tariffs, Time, and Tradecraft: Why “America First Tariffs” Are Rewriting Policy, Not Economics

Input

Modified

America First tariffs avoided an immediate recession but shifted trade into geopolitical strategy Short-term stability hides real household costs and long-run productivity risks The real test is whether tariffs build lasting capacity without weakening institutions

When the U.S. started using new tariffs, it was like adding a tax of about 1–2 percent to what U.S. families spent each year. This might not seem like much for the whole country, but it showed a big change: trade is now being used as a tool to achieve a country's goals. The difference between protecting our industries and gaining power has become unclear. What was once a short-term fix is now being used to influence other countries. This is important because the old economic ideas that said tariffs would hurt us assumed markets would remain unchanged and global trade would go smoothly. But that's not the case anymore. This new approach, which began as a promise during the election, is now actively changing our relationships with other countries, how goods are supplied, and our plans for industry. If teachers, school leaders, and politicians just see this as a small economic event, they'll miss the bigger picture: we need to teach students and train leaders how to handle an economy where trade is used to gain an advantage, not just to affect prices.

Brookings Institution — America First tariffs and the short-run reality

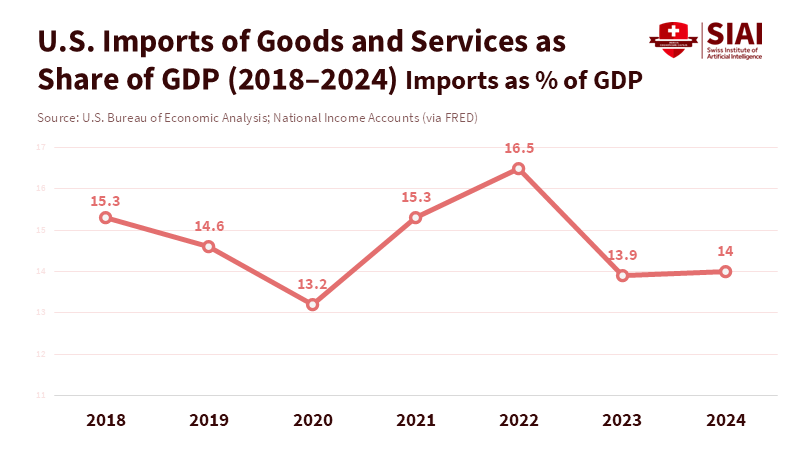

The main idea here is simple: we should see the America First tariffs as a means to achieve goals abroad, and only then as a means to manage the economy. The concerns that people expressed early on – that they would cause downturns, runaway price increases, or trade collapses – didn't happen as quickly as expected. Imports were about 13.9 percent of the U.S.'s total economic output in 2023 and about 14.0 percent in 2024. This means that shocks to imports affect the economy more slowly than previously thought. This helps explain why putting tariffs on many products didn't cause the economy to collapse immediately.

But these numbers, which might make us feel better in the short term, hide two important facts: the burden of higher prices is real for many families, and tariffs alter the incentives to invest and to seek new sources of goods; these effects increase over time. When a policy alters how companies think about the future of trade, it alters where capital is invested and which skills are developed. These changes, not short-term economic fluctuations, determine how productive we will be in the long run.

Just because things are stable in the short term doesn't mean the policy is succeeding. The trade numbers show why there weren't big economic effects right away, but they also hide the stress that is being put on families. Tariffs increase costs for the things that families can least afford – groceries, supplies for small businesses, and school materials – and spread the pain across all the industries that rely on global trade. The result is a stable overall economy, but with a growing hidden tax on everyday spending and business choices. This is clear in many datasets and should lead to a different discussion about how to be strong, not just how to recover.

Tariff math, household pain, and the evidence through 2025

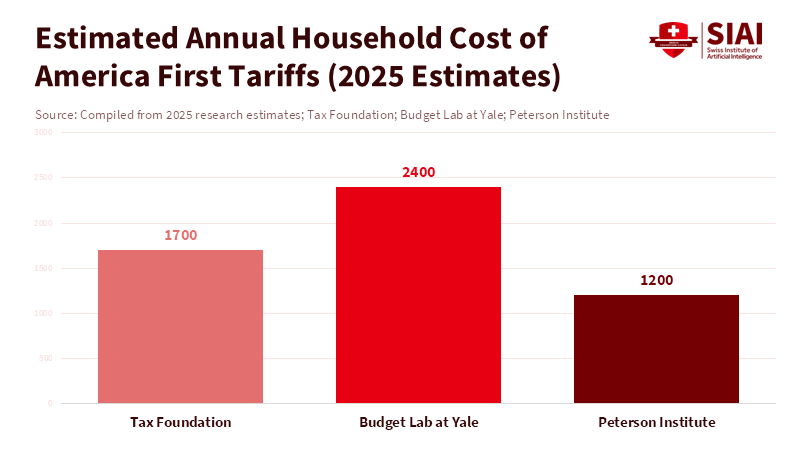

Data from 2023–2025 show a consistent pattern: the tariffs implemented as part of the America First plan raised consumer prices by a noticeable amount overall and shifted wealth from the poor to the rich. Independent groups that measured the cost of the 2025 tariff package to families found that the average family lost between $1,000 and $2,400 per year. This amount depends on which tariffs are included and whether we assume that businesses pass the full cost of the tariffs to consumers. These estimates employ different methods, but they generally indicate that the policy increases prices in a manner that disproportionately harms lower-income families. A separate study found that retail prices of newly taxed goods increased significantly in late 2024–2025, which contributed to the rise in core inflation in certain areas. Together, these numbers indicate that the policy increases consumer charges, even as the overall economy continues to grow.

Why tariffs were put in place: supply chains, alliances, and industrial overcapacity

If we view tariffs solely as a simple economic issue, we'll miss the reasons they were chosen. The rationale behind the recent tariffs is not so much about fixing a simple market problem as about addressing long-term overproduction and changing our reliance on other countries. Global steel production exceeded demand in 2023, and growth was primarily in non-OECD countries. Those imbalances led to disputes over dumping and subsidies, which national industries used as reasons to advocate for tariffs. The tariff program was selected as the instrument to punish and incentivize the relocation of supply chains. It's meant to change behavior both in other countries and here at home, not just to protect a single factory.

This strategy affects our relationships with other countries. Allies don't see the U.S. imposing high tariffs as just a change in domestic policy. They see it as a sign that the established international system can be ignored for short-term gain. That changes how countries work together. Trade policy is now as much about building alliances as it is about helping the domestic industry. For teachers who are creating courses on international economics and politics, this means they should include strategy and trade theory. Students need to learn how tariffs affect different groups, the history of trade law, how countries negotiate, and the limits of international solutions. Otherwise, leaders won't be prepared for situations where they have to weigh economic costs against the benefits of international relations.

The long-term risk to productivity, innovation, and education

The main problem with tariffs is that they affect things over time. Tariffs might protect an industry in the short term, but the long-term costs may include slower productivity if companies stop improving or if domestic suppliers don't face as much competition. Investment choices depend on how open businesses expect trade to be. If businesses expect trade to be restricted for an extended period, they may forgo investments in technologies that rely on imported inputs or alter their production in ways that reduce long-run productivity. The effects on productivity occur slowly and unevenly, making them difficult to detect in the news. However, they are the primary means by which these policies will either support or weaken our standard of living over time.

Education is at risk in several ways. First, higher supply costs reduce school budgets and leave less money for staff, training, and technology. Second, the outcomes of industrial policy affect local job markets. Areas that gain protected factories might see job growth in the short term, but weaker motivation for workers to train and move to new jobs. Third, university research and industry training in goods-trading industries depend on international cooperation and equipment flows. Tariffs that restrict imports can increase costs for research labs and slow down innovation. Politicians, therefore, need to view tariff policy as a factor affecting education, not simply as a tool for trade. This entails carefully planning budgets, making procurement more flexible, and expanding training programs that prepare for structural changes rather than reacting to them.

Addressing criticisms with evidence

There will be some familiar criticisms of this analysis. One common argument is that tariffs brought back investment and jobs, thus improving things in the long run. The evidence is mixed. According to the Council on Foreign Relations, while some companies announce intentions to bring production back to the United States, such announcements don't always lead to actual investments. Often, these promises depend on incentives like tax breaks or subsidies, and manufacturing may still rely on imported parts. When companies made significant investments, the effect on local productivity was positive. When companies just moved low-value assembly work, the gains were small. Another argument is that tariffs are needed to counter unfair practices by other countries. This is partly true – sometimes countermeasures are justified – but the solution is important. Targeted actions against dumping and subsidies, along with joint international action, protect the international system while tackling the problems.

According to the Brookings Institution, broad and long-term tariffs tend to increase costs for new construction, renovations, and affordable housing, and can disrupt cooperation without fully addressing the market issues they target. The evidence suggests that tariffs are more effective when they are carefully targeted, limited in duration, and paired with domestic investment to strengthen capabilities. But broad, indefinite tariffs create uncertainty and real costs for families and schools. The policy we are observing is significant not only because of what it does but also because of its magnitude and duration. That size explains why even small changes in household spending can translate into substantial shifts in wealth and why education systems must respond.

What should educators, administrators, and politicians do now?

First, plan budgets with different scenarios in mind. Administrators should develop plans that assume higher supply costs over two to five years and identify expenses that can be deferred without compromising education. Second, use flexible contracts for school supplies to allow quick changes; diversify contracts by region so that a tariff on one supply chain doesn't affect an entire district. Third, invest in programs that support workers' transitions by linking short-term protection to long-term skill development. Subsidies should require training commitments and improvement plans. Fourth, universities and vocational programs should update their curricula to include knowledge of supply chains, international strategy, and basic industrial policy, so that future leaders can handle situations in which trade policy is used tactically.

For politicians, the task is to be clear about the trade-offs. If tariffs are used as tools to gain an advantage, then the political benefits must outweigh the costs to consumers and education. That calls for clear expiration dates for tariffs, targeted help for low-income families, and international cooperation where possible. Otherwise, tariffs become a tax without a clear plan to turn protection into permanent strength.

The headline that tariffs didn't cause the economy to crash in the first year misses the bigger story: the America First tariffs have turned trade policy into a tool for international competition, and that shift changes the motivation for investment, education, and family life. Short-term economic stability can coexist with growing economic pain for families, and it can also lead to slow, damaging changes in productivity that only become apparent over time. The right response is not to blindly defend either open trade or protectionism, but to find a moderate approach: use targeted measures when there is evidence of problems, combine any protection with clear requirements to modernize, protect low-income families from price increases, and give educators and local administrators the tools to manage uncertainty. If we don't teach these skills, the next generation of leaders will inherit policies they don't understand and budgets they can't manage. That is the real test of whether the tariff experiment will be a strategic success or a costly mistake.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Braumiller Law Group (2024) Tariffs and the temptation to use them as geopolitical leverage. Braumiller Law Group.

Brookings Institution (2024) Did America First tariffs work? Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Budget Lab at Yale (2025) The state of U.S. tariffs: 2025 update. Yale University.

Council on Foreign Relations (2024) Geopolitics of Trump tariffs: How U.S. trade policy has shaken allies. New York: CFR.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (2025) Shares of gross domestic product: Imports of goods and services (B021RE1A156NBEA). Data series via U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2024) Latest developments in steelmaking capacity and outlook. Paris: OECD.

Peterson Institute for International Economics (2025) Estimates of household costs of U.S. tariff policy. Washington, DC: PIIE.

Tax Foundation (2025) Trump tariffs: The economic impact of the Trump trade policy. Washington, DC: Tax Foundation.

World Trade Organization (2024) Tariff profiles: United States of America. Geneva: WTO.

Yeni Şafak (2024) Tariffs as geopolitical weapon: U.S. trade policy reshapes alliances, not deficits. Istanbul: Yeni Şafak.

Comment