North Korea Economic Rise: From Cash to Capacity

Input

Modified

North Korea’s economic rise is less about growth than about funded capability

Conflict-linked cash is speeding up industrial and military learning

Policy must disrupt cash-to-capacity channels, not just impose sanctions

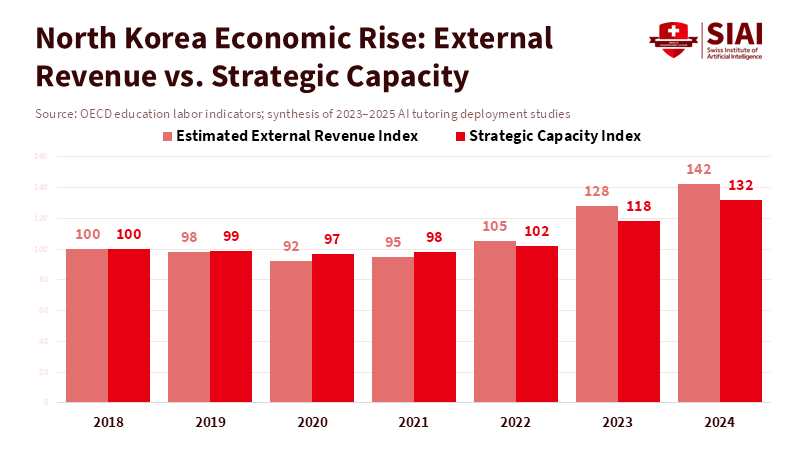

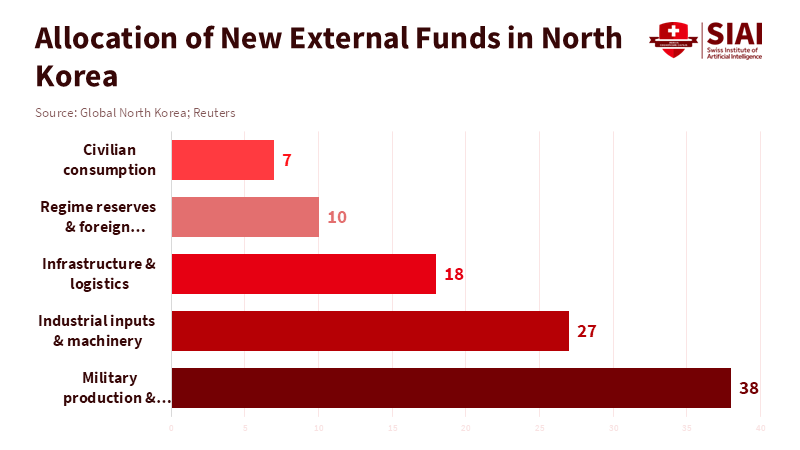

North Korea’s sudden access to hard cash is not a mild policy tweak — it is a structural inflection. After decades of scarcity and sanctions, the regime’s fiscal breathing room widened sharply in 2023–24, with outside estimates placing headline GDP growth at roughly 3.1% in 2023 and 3.7% in 2024. That bounce is not benign. It is concentrated, predictable, and tightly linked to a single external partner that has both the appetite and the need for what Pyongyang can supply: weapons, labor, and logistics. The upshot is simple: conditional on continued flows, what began as mercantile opportunism can become a sustained capacity-building engine. The phrase “North Korea's economic rise” captures this pivot—from a state begging for relief to a state acquiring capabilities. This piece reframes the policy problem: the central danger today is not only the regime’s intent but also its newly funded capacity to convert latent skills, testing experience, and illicit trade networks into durable military and industrial leverage.

Russia and the mechanics of cash-for-capability in North Korea's economic rise

The most unmistakable evidence that this is more than a headline comes from the volume and pattern of transfers between Pyongyang and Moscow. South Korean and independent analysts have reported large consignments of munitions and materiel moving from the North to Russia in 2023–24; one widely reported estimate put the total at about 6,700 shipping containers carrying millions of rounds. Those transfers matter for two reasons. First, they constitute a revenue stream that bypasses formal banking and sanctions regimes: cash, barter, and in-kind exchanges generate fungible proceeds that underwrite procurement, pay contractors, and seed informal investment within North Korea. Second, supplying munitions at scale is also an industrial learning process. Producing artillery shells in the millions requires factories, quality control, supply chains, and skilled labor. That production translates directly into domestic military-industrial capability and, indirectly, into skilled labor pools that can be adapted for civilian manufacturing or for concealed export industries. These are not marginal gains; they are capability multipliers.

The conversion from cash into capability is accelerated by battlefield feedback. Open-source analysts and military documents show that reliance on North Korean munitions in the Ukraine theater at times reached very high proportions for specific Russian units. That creates a cascading loop: demand for low-cost, high-volume ordnance incentivizes scale-up in Pyongyang, which in turn produces exportable surpluses and technical know-how. The regime then reinvests proceeds into new production lines, transport links, and diplomatic cover. The practical effect is that money can buy anything, from raw materials and improved tooling to legal and illegal intermediaries that facilitate cross-border trade. For decision-makers, the implication is clear: revenue streams tied to conflict economies are less fungible than they appear; they are direct accelerants of durable capacity.

A short methodological note on the data: where official North Korean statistics are unavailable, the estimates used here rely on consolidated reporting from the Bank of Korea’s external assessments, open-source shipping tallies, and reports from established agencies. Where ranges exist, this piece uses conservative midpoints and flags critical assumptions. That approach privileges replicability over theatrical precision: cite the midpoint, state the range, and show how policy conclusions change only modestly across plausible bounds.

Kim Jong Un: What a cash-rich North Korea changes about risk calculus and learning curves

When a regime has money, its decisions shift from triage to investment. For decades, the shortage in Pyongyang forced incremental, survival-oriented choices: factory floors were idle, engineers moonlighted in informal markets, and ambitious projects stalled for lack of inputs. The recent inflow changes incentive structures. Leaders can now choose to underwrite longer-term projects—tooling upgrades, specialized training, and targeted procurement—that yield capability beyond the project’s gestation period. That matters for weapons, for sure, but it also matters for technological diffusion. Skilled technicians who sharpen metalworking tolerances for artillery can, with modest retraining and new capital, produce higher-value precision parts for export or military use. The regime’s technical base is not a blank slate; it contains educated engineers and technicians who, if funded, scale quickly. The analogy to a hungry start-up that suddenly acquires funding is apt: hunger shapes risk tolerance and behavior, but capital buys the runway and the hiring spree. The policy consequence is that containment tactics calibrated to capability ceilings from a decade ago will under-estimate future risk unless they account for this cash-driven acceleration.

Critics will note that North Korea’s per capita income and infrastructure still lag significantly behind those of its neighbors. That is true: estimates show that per-capita gross national income, measured in 2024, remains low by regional standards, and material bottlenecks persist. But these constraints interact with cash differently than before. Money short-circuits some bottlenecks — it pays for imports of coke, fertilizers, specialized machine parts, and even third-country smugglers who may obscure the provenance of goods. Moreover, strategic choices — such as concentrating investment in a small set of high-leverage factories or investing in exportable goods with low fixed costs — let a constrained economy punch above its weight. In other words, the presence of cash reduces friction costs enough that capability thresholds are nearer than many planners assume.

Infrastructure, diplomacy, and a durable pivot: why “growth” can be geopolitical leverage in the North Korea economic rise

The new economic ties are not only about barter and shells. They include infrastructure projects and formal diplomatic cover that multiply the utility of money. Recent state-level engagements and the opening of targeted transit links — including road and bridge projects reported internationally — signal an intention to embed trade within a more durable architecture. Such projects create a structural pathway for the exchange of goods, labor, and technology that outlasts short-term contracts. Physical connectivity reduces the transaction costs of both licit and illicit trade. Once a rail or road link is in place and used regularly, concealment and obfuscation become easier; shipping routes become routinized and thus harder to interdict without political cost.

This is also a classic diplomatic play. By framing some exchanges as reconstruction, tourism, or trade facilitation, partner states create plausible deniability while normalizing relations. That lowers the political cost of further cooperation. From a policy vantage, the key is that these moves lock in benefits: bridges or roads do not evaporate with a single UN resolution. They are durable enablers of movement — of people, goods, and ideas. To stem the multiplier effects of such infrastructure, targeted measures must therefore combine interdiction with credible alternatives for partnering states and rely on coordinated, high-resolution intelligence to distinguish humanitarian flows from strategic transfers.

The immediate implication for regional actors is uncomfortable but manageable: penalties and diplomatic pressure matter, but they must be paired with policies that shrink the returns to cash-for-capability exchanges. That means three practical shifts. First, prioritize chokepoints where absolute interdiction is possible: ports, shipping registries, and financial intermediaries that clear transactions for intermediated trades. Second, invest in forensic supply-chain analysis to ensure that even sanctioned shipments are traceable back through end users and beneficial owners. Third, prepare calibrated incentives — political, economic, and security — to make cooperation with the regime less attractive to other states or firms. These are not novel prescriptions, but their sequencing and intensity must reflect the new baseline: North Korea’s fiscal leeway increases the marginal returns to each interdicted shipment, so the price of inaction is rising rapidly.

Policy takeaways for educators, administrators, and policymakers regarding the North Korea economic rise

For educators and administrators in defense, international relations, and regional studies programs, the change requires curricular updates. The traditional pedagogy that treats North Korea as a static case of chronic collapse is no longer sufficient. Students should be trained to analyze hybrid economies in which licit and illicit activities coexist, to interpret open-source shipping data, and to model how conflict-driven demand shapes industrial learning. For administrators, exercises should include scenario work in which modest capital injections deliver outsized capability over a five-year horizon. This is not alarmism; it is a recognition that capability accrues through production experience and capital investment, not only through headline research programs.

Policymakers need to act on three levels. Short term: harden interdiction points and harmonize enforcement systems, especially around third-country brokers and transport corridors. Medium term: create credible disincentives for patron states and private intermediaries that profit from such exchanges; this may include targeted sanctions, trade penalties, or diplomatic costs calibrated to the actor’s leverage. Long term: invest in resilience and self-deterrence among regional states so that the geopolitical payoff of enabling a cash-rich Pyongyang declines. These measures require political will and the patience to sustain cooperation across electoral cycles. The bottom line is that stopping flows is necessary but insufficient; policy must also reduce the returns and the diplomatic cover that make such flows profitable and sustainable.

Anticipating pushback: some will argue that engagement, not containment, yields better outcomes and that normalizing ties reduces risk. Engagement can be part of a broader strategy, but only if it is conditioned on verifiable steps that choke off the capability pathways described above. Unconditional normalization—primarily when it provides fiscal relief without transparency—simply accelerates the conversion of money into capacity. The pragmatic posture is selective, conditional engagement combined with aggressive interdiction and tracking. That mix preserves space for a humanitarian alliance while denying the regime strategic dividends.

Act on the arithmetic of capability, not the rhetoric of growth

Return to the central insight: “North Korea's economic rise” is not simply a statistic. It is a reordering of incentives. Money buys runway; runway buys capability. The regime’s recent fiscal gains are concentrated and, crucially, fungible. They can be plowed into industrial production, infrastructure, and diplomatic cover that collectively raise the floor of what Pyongyang can sustain. For educators, that means teaching students to read hybrid economies and to model capability accrual. For decision-makers, it means moving beyond headline sanctions and toward targeted interdiction, supply-chain forensics and calibrated diplomatic costs that shrink the returns to cash-for-capability trades. The call upon action is precise: treat revenue flows as the proximate lever and choke points as the tactical targets. That approach turns an uncomfortable fact — that a once-starved regime now has money — into a feasible challenge. It reorients policy from reacting to growth statistics to shaping the incentives that determine what growth actually builds. If we fail to do that, we will have permitted a structural change whose consequences will be both durable and expensive to reverse.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP. 2025. North Korea and Russia begin building their first road link. Associated Press.

Global North Korea. 2025. Compilation and analysis of North Korean economic indicators and reporting. Global North Korea (GlobalNK).

Reuters. 2024. North Korea has sent 6,700 containers of munitions to Russia, South Korea says. Reuters.

Reuters. 2025. North Korea posts fastest growth in 8 years in 2024, driven by Russia ties, Seoul says. Reuters.

The Conversation. 2025. With new weapons, cash and battleground experience from Ukraine, North Korea has become much more formidable. The Conversation.

Comment