When FDI Buys Into a Chain, Not a Country: Rethinking Success in the Age of Cross-Border Production

Input

Modified

FDI now succeeds by linking into global value chains, not by expanding domestic production German investment in China uses local labor and efficiency while value stays global Policy should shape how FDI integrates into chains, not just how much arrives

Global foreign direct investment fell to approximately $1.3 trillion in 2023, even as large manufacturing projects continued to reshape where firms locate factories and engineers. That paradox—less headline FDI but stubborn, targeted project flows—is the frame we need: the success logic of FDI no longer lives primarily in a host economy’s domestic spillovers but in how healthy investment plugs into FDI in global value chains. Firms now site plants to access foreign labor practices, machine-level process efficiencies, and cross-jurisdictional supplier networks rather than to seed a broad local ecosystem. The economics are simple in form but sharp in effect. A firm brings capital and product design; it taps another country’s labor (L) and operational technology or factory control (A); and the output competes on global markets, not only locally. This shift—from “within-country” linkages to “across-country” chain participation—means that traditional policy metrics for FDI success are often mistargeted. The data supporting this shift are recent and measurable; they require us to change how educators, administrators, and policymakers teach, measure, and negotiate investment.

The analytic reframing: from domestic spillovers to cross-border chain access

The standard story of FDI as a channel for local capital accumulation and technology transfer—think factories that buy local inputs, train local managers, and generate supplier networks—still exists in fragments. But it is no longer the dominant template in many strategic sectors. Reframing means recognizing that the primary margin of value creation in modern FDI lies in positioning within an international sequence of specialized tasks. In that configuration, a foreign plant’s “success” is judged by its access to transnational suppliers, its ability to embed into multi-tier sourcing networks, and its contribution to a firm’s global output rather than by the extent to which it sources domestically or creates broad-based local linkages. This reframing matters because policies and pedagogy that assume the old model will misread incentives, misallocate incentives, and misprepare managers. The CEPR literature and recent empirical reviews foreground this conceptual shift: the link between FDI and aggregate growth has weakened as production has fragmented across borders, not because investment has lost value, but because its value is redistributed across countries in ways that traditional national statistics do not readily capture.

To make this concrete, take the automotive sector, where German firms have massively reoriented investment decisions in the last three years. German greenfield and expansion projects in China rose sharply in 2024–25, concentrated in assembly, R&D nodes, and digital factory platforms rather than in broad supplier ecosystems that buy locally across many upstream tiers. Firms explicitly cite access to China’s dense auto-parts supplier network, flexible contract manufacturing, and advanced factory automation as reasons for siting capacity there. These investments therefore harness Chinese labor (L) and factory-level technical efficiency (A) while preserving the parent’s capital (K) and design IP for global output. Reporting compiled for international outlets documents a marked rise in German investment flows to China in 2025—projects concentrated in auto manufacturing and related tech—that bolsters the argument that the modern FDI bargain is about chain position, not domestic embedding.

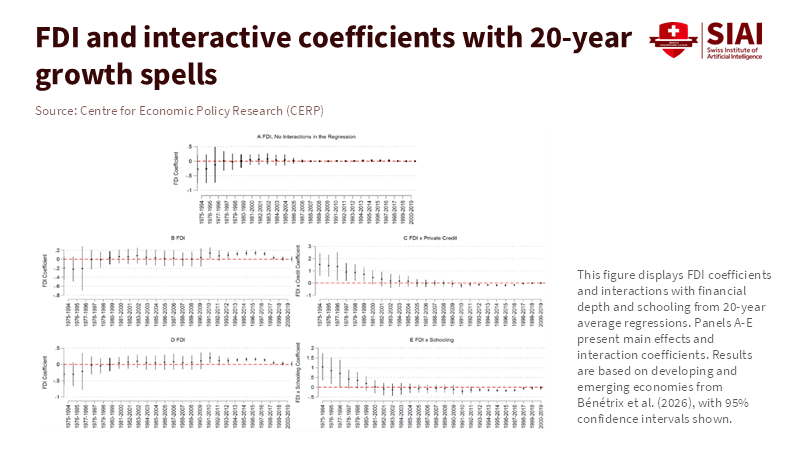

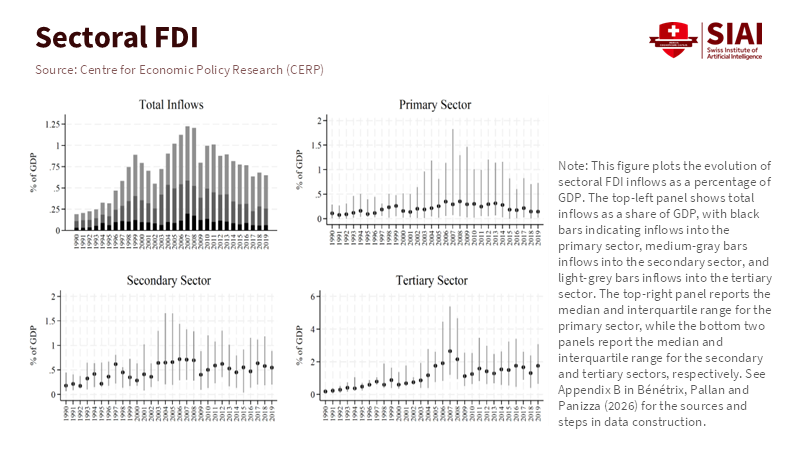

What recent data show and how we estimate effects

The complex data supporting this reinterpretation come from three complementary sources: macro FDI flows (UNCTAD and national compilations), firm-level announcements and project databases (press reporting and investment trackers), and sector studies that map supplier networks. UNCTAD’s World Investment Report reports that global FDI in 2023 stood near $1.3 trillion—down modestly from 2022—while sectoral snapshots show continued concentration of greenfield manufacturing projects in regional hubs. At the same time, trackers and reporting reveal that German firms’ investment commitments to China rose to multibillion-euro levels in 2024–25, with the auto sector accounting for a large share. To translate these into economic implications, we use a simple production-function accounting approach: output at a foreign plant can be modeled as Y = A × K × L, where A reflects technological and organizational efficiency at the plant and in its immediate supplier network, K is capital supplied by the investing firm, and L is local labor and routine skills. What changes in the modern arrangement are that the host country often supplies A and L but not broad upstream K or design spillovers—the foreign firm internalizes capital and intellectual property and routes most upstream purchases through transnational suppliers rather than developing them locally.

These estimates matter because they change how we measure “local content” and “technology transfer.” If a German plant in China sources 60–80% of its automotive parts from regional suppliers and imports high-value components or tooling from Germany, its local content measure appears high on one metric (parts purchased locally) but low on another (high-value capital goods, R&D, and managerial functions). Thus, a naive reliance on a single local-content metric can misclassify investments as deeply embedded when, in value terms, the high-margin activities remain concentrated in the home country. Recent reporting and firm disclosures support a mixed pattern in the automotive sector: local assembly and supplier purchases coexist with retained capital intensity and parent-company control over intellectual property and complex components.

Policy and pedagogical implications: how we must change incentives and curricula

For policymakers, the practical implication is immediate: incentive schemes and performance metrics should reward firms for meaningful linkages to local supplier development, sustained managerial integration, and shared R&D commitments—not merely the headline of megaprojects or local employment counts. Subsidies that ignore whether a new plant will catalyze multi-tier domestic supply chains risk paying for activity that primarily strengthens global, not local, value capture. A more surgical policy toolkit would target joint investments in supplier capabilities, co-funded training programs to upgrade local machine maintenance and digital skills, and conditions that encourage local co-ownership of tooling or licensing to spread higher-margin activities. Educationally, curricula for trade, development economics, and business strategy must reorient to teach students how to map and negotiate chain position: how to value forward and backward linkages, how to design contractual mechanisms that convert chain access into local capability, and how to evaluate cross-border spillovers in value and skills rather than in employment alone. These changes reframe success from “plant opened” to “chain embedded.”

Administrators and program designers in universities and public training bodies must also change their measurement dashboards. Traditional KPIs—number of new foreign firms, jobs created, and headline investment amounts—remain useful but incomplete. New KPIs should include supplier-upgrading metrics (the percentage of local suppliers meeting quality and delivery standards after 2 years), local R&D co-investment ratios, and durable upskilling outcomes. Implementation is pragmatic: tie public grants to verifiable supplier development milestones and require transparent reporting of procurement shares by tier. This is not protectionism; it is leverage. If a government can use modest co-investment to shift a foreign project from a “plug-in” assembly node to a co-design partner over time, the local economy captures more of the global rent and gains lasting absorptive capacity. The recent German experience in China—where investment can increase without creating proportional domestic K or upstream deepening—illustrates both the risk and the opportunity of more targeted policy design.

Anticipating critiques and rebuttals: common objections answered

Critique one: “This view undervalues jobs and short-term growth from assembly plants.” The rebuttal is twofold. First, jobs matter and should be part of any agreement, but counting jobs alone is insufficient; low-margin, easily relocatable employment creates vulnerability rather than durable development. Second, policy can and should secure improvements in job quality (training, contractual wage floors, apprenticeship linkages) that make jobs less footloose. Critique two: “Countries cannot force deep linkages without turning away investment.” That assumes a binary choice between unconditional openness and closure. The evidence suggests otherwise: conditional, transparent co-investment and supplier development programs attract investment while steering its form. Several middle-income economies have successfully negotiated phased content requirements contingent on public support. When firms perceive credible, cooperative industrial policy rather than abrupt protectionism, they often accept staged local sourcing and joint R&D. A third critique notes that geopolitics may push firms to relocate; this, in turn, increases the urgency of smart policy. If investment is motivated by risk diversification rather than local market access, policymakers must ensure that diversification yields durable local capabilities rather than merely a relocated assembly line. Recent policy debates in the EU about how to manage strategic relationships with China underline that these are practical—not theoretical—concerns.

Teach, measure, and bargain for chain-capability, not just capital

The old yardsticks—headline investment totals, job counts, and factory openings—still tell part of the story, but they are blunt instruments for a fine-grained reality. FDI in global value chains now often buys access to a foreign country’s labor practices and factory efficiency while keeping capital, high-margin parts, and strategic control at home. That configuration can benefit both investor and host, but only if policymakers, academics, and business leaders change how they teach, measure, and negotiate investment. We should teach managers to value the chain position, train policymakers to design co-investment and supplier-upgrading targets, and measure success with indicators that capture durable capability rather than momentary employment. The German auto example is a caution: significant investment can coincide with limited domestic capture unless bargaining and policy design are aligned to convert chain access into local capability. The call to action is straightforward: move incentives from paying for plants to paying for capability; retool curricula to include chain mapping and contracting; and demand transparent supplier and R&D commitments from major projects. That is how we turn FDI from a headline into a lever for lasting development.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bénétrix, A., Pallan, M., & Panizza, U. (2026). FDI and growth in the age of global value chains. Centre for Economic Policy Research, VoxEU Column.

EIAS. (2023). German Automotive FDI in China: Policy Brief No. 06/2023. European Institute for Asian Studies.

MERICS. (2024). German carmakers are placing a risky bet on China. Mercator Institute for China Studies, Commentary.

Reuters. (2026). German firms' China investments driven to four-year high by US trade wars.

UNCTAD. (2024). World Investment Report 2024: Investment facilitation and governance.

Comment