The data center boom is not the new factory — unless we rewrite the deal

Published

Modified

Data centers are not modern factories and rarely create broad local prosperity. They often raise local power costs while delivering few permanent jobs. Only strict public-benefit energy rules can rebalance the deal.

The data center boom is changing small towns and electrical networks faster than most local governments can track. Global electricity use by data centers reached the hundreds of terawatt-hour range recently, and industry forecasts see consumption roughly doubling within a decade — a scale shock that would make a single new campus as consequential for a rural grid as a mid-sized steel plant once was. That stark fact reframes our question: are data centers destined to play the same civic and economic role that factories did in the 20th century, building broad local prosperity through plentiful jobs and supplier networks, or will they instead function as capital-intensive, low-employment facilities that extract affordable power and offer limited community payoff? This column argues the latter is the default outcome today. The differences among those futures depend on policy: electricity contracts, tax incentives, and whether each data center must be paired with on-site generation or with community power programs that intentionally return value to local residents. Without those bargains, the “21st-century factory” claim collapses into a short construction boom and long-term local costs.

Why the data center boom looks factory-like — and why that resemblance misleads

The raw numbers explain the analogy’s appeal. Modern hyperscale data centers require land, roads, cooling and, above all, immense, reliable power. That visible footprint resembles a factory campus: new buildings, heavy trucks, an inflow of contractors, and municipal revenues tied to construction and property. In many places, officials and economic development teams sell the project this way: quick construction jobs, higher tax bases, corporate donations and the hope of a nascent tech cluster. Those short-lived gains are real. Construction phases can employ hundreds or thousands of workers for months or years. Local suppliers benefit for the duration. Municipal budgets experience an immediate spike in receipts attributable to permit fees and developer payments. Those outcomes are the origin of the factory metaphor — a large, visible employer that forms local life.

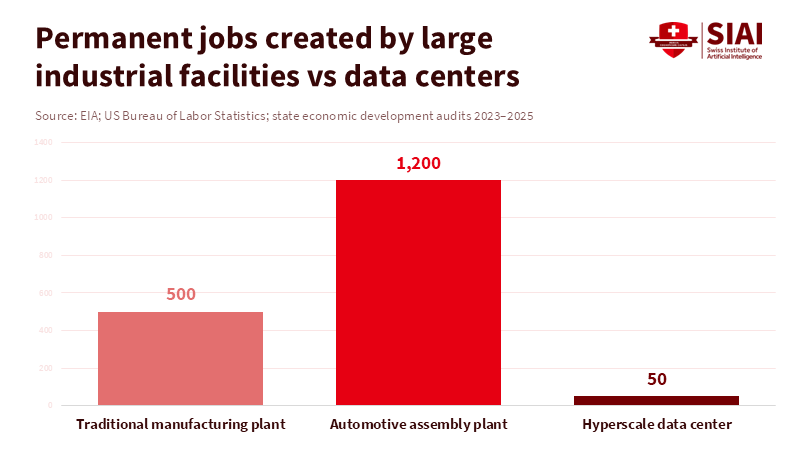

But the similarity stops when facilities begin steady operations. Unlike a 20th-century factory that required large, skilled, and semi-skilled local labor forces for day-to-day production, many modern data centers run on automation and remote management. Once built, the permanent on-site workforce is often small relative to a site’s capital value and energy draw. The pattern emerging from recent studies shows a recurring mismatch: big infrastructure and power demands, modest operational payrolls. That means the civic bargain that once justified factory siting—dozens or hundreds of durable local jobs plus supplier ecosystems—is not automatic for data centers. The policy lesson is plain: if a community treats a data center solely as a factory replacement, it will likely end up with an expensive power bill and a handful of long-term jobs, not the broad prosperity promised.

Energy, bills and the hidden transfer of value in the data center boom

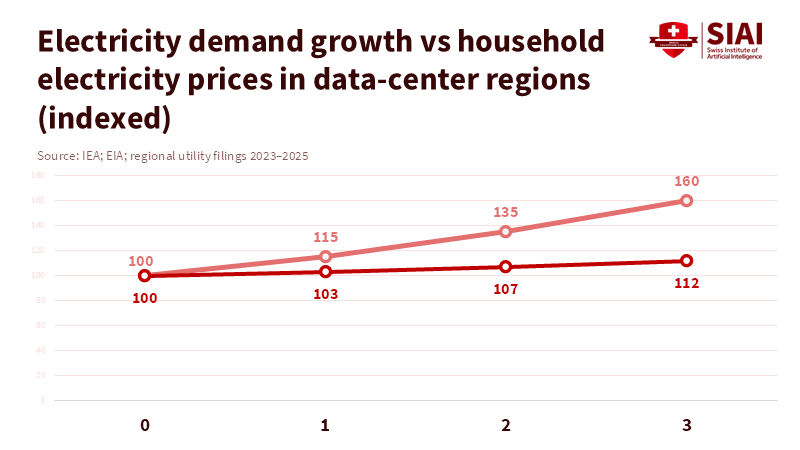

Power is the fulcrum. Data centers’ electricity demand is already substantial; reputable sector projections indicate that global data-center electricity use will increase substantially in the near term. That increase matters at the local level because grid upgrades, emergency generation and firm capacity all carry costs. Utilities and developers negotiate who pays. If those costs are socialized—through rate changes or long-term cost-recovery mechanisms—local ratepayers may face higher bills, while the data center benefits from access to cheap, reliable power. In effect, the private benefit of hosting a data center can become a public cost unless contracts are reformed.

That transfer is not hypothetical. Where clusters concentrate, utilities have warned that new, sudden loads require new substations, reconductoring, or even fossil-fuel backup to meet reliability standards during peak demand or outages. Those investments are often recovered through rate mechanisms that touch every household and small business. The visible result is an alarming local complaint: residents see new, gleaming campuses and then receive higher bills. For many small or rural communities, that outcome is politically explosive because it reverses the expected social contract. The structural fix is to rewrite the bargain: require onsite firm capacity that benefits the community; demand lower wholesale rates for residents; or tie grid upgrades directly to shared community pricing programs. Otherwise, the data center boom behaves like an energy parasite — great, concentrated demand that saps local affordability while producing limited local employment.

Jobs, taxes and the gap between promise and reality of the data center boom

Employment claims have driven many municipal approvals. Industry and allied consultants frequently produce projections that include indirect supply-chain jobs, and some national studies report figures that appear striking when read without context. Those broader estimates frequently include induced employment—the jobs supported across an entire national supply chain—and one-time construction roles. In contrast, direct, permanent on-site employment at a single hyperscale campus is often modest: dozens to low hundreds, not thousands. This distinction matters because communities vote, plan schools, and approve zoning in accordance with expectations regarding durable jobs and tax flows.

Recent audits and state studies show the dissonance. Detailed, state-level reviews show that while capital investment and construction increase short-term employment and local revenues, recurring operations generate far fewer local jobs than advertised—and tax deals often blunt the fiscal gains. When generous exemptions or equipment tax breaks are granted to attract projects, net long-term revenue may decline, leaving local budgets to shoulder infrastructure and service costs. Critics maintain this represents a poor return on public incentives. Supporters counter that national supply chain impacts and corporate tax remittances justify incentives. The sensible policy path recognizes both truths: count direct permanent roles separately from temporary construction work and design incentive packages that scale with demonstrable, long-term local benefits. Without that discipline, the data center boom will deliver a construction windfall and then a thin, steady stream of local benefits—far from the mass-employment factories once offered.

A practical bargain: SMRs, community power, and rewriting the deal for the data center boom

If data centers will not reliably create large-scale local employment, then communities must demand a different kind of return: shared, affordable, and resilient energy. Small, small reactors (SMRs) and other firm, local generation options have moved from abstract ideas to concrete corporate experiments. Major cloud providers have announced agreements and investments to pair data centers with advanced nuclear or long-term firm capacity procurement. When implemented, such arrangements can insulate grids, reduce marginal power costs for local customers, and provide a revenue or capacity stream that can be repurposed for public goods. The crucial policy requirement is simple: require every major new campus to demonstrate community power benefits that lower household or municipal rates or to dedicate a concrete portion of firm output to local public use.

There are multiple practical forms this bargain can take. An SMR or co-located firm generator, jointly owned with the utility, can deliver lower-cost, uninterrupted power to a local tariff band for residents and municipal facilities. Alternatively, a community benefit agreement can lock a data center into long-term payments to a local energy trust that subsidizes electricity for low-income households and public schools. Another option is a capacity-sharing rule: a percentage of off-peak power is sold back at cost to local businesses. Each design needs clear, enforceable metrics and independent auditing to prevent creative accounting. The point is not to stop data centers, but to align their massive energy footprint with durable, local public value, rather than abandoning communities to bear the external costs while tech firms capture private gains.

Reclaiming the civic bargain in the data center boom

The data center boom will not, on its own, become the 21st-century factory that spreads prosperity widely. The default pattern is one of enormous capital investment, intense short-term employment, and small operational payrolls — coupled with long-term pressures on energy systems and local affordability. Communities can accept that reality or they can legislate a different bargain: require firm generation commitments, community-priced electricity, and incentive structures that scale with demonstrable local benefits. These are not theoretical fixes. There are emerging corporate and utility experiments pairing data infrastructure with SMRs and long-term power contracts — moves that, if replicated under public oversight and with binding community returns, would produce something closer to a factory’s civic role. The policy test for the next wave of siting decisions is this: can a locality negotiate a binding, transparent package that turns raw kilowatts into local wealth, not local cost? If the answer is no, then the towns that host these campuses will have traded a short boom for a long bill. It is time to make the data center boom pay for the people it affects.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Energy Information Administration (IEA). 2025. Energy and AI: Energy demand from AI. International Energy Agency.

JLARC (Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission). 2024. Data Centers in Virginia. Commonwealth of Virginia.

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Shehabi et al.). 2024. United States Data Center Energy Usage Report. LBNL-2001637.

Northern Virginia Technology Council (NVTC). 2024. The Impact of Data Centers on Virginia's State and Local Economies.

PwC / Data Center Coalition. 2025. Economic Contributions of Data Centers in the United States 2017–2023. PricewaterhouseCoopers.

Financial Times. 2024. Google orders small modular nuclear reactors for its data centres.

Food & Water Watch. 2026. The Illusion of Big Tech's Data Center Employment Claims.

Congressional Research Service. 2026. Data Centers and Their Energy Consumption (CRS product R48646).

Comment