Japan’s Growth Problem Is Not Work Hours, but Productivity

Input

Modified

Japan’s growth problem is not a lack of effort, but weak output per hour Extending work hours raises costs without fixing productivity or wages Policy should shift from time worked to skills, management, and productivity gains

Japan's hourly productivity is about $56.8, while the OECD average is closer to $70. This difference isn't just a minor accounting issue that can be fixed by working a few extra hours. It's a fundamental problem that more time spent alone at work won't solve. Leaders who talk about economic growth as simply a matter of putting in more hours are confusing effort with results. Working longer weeks might increase the total GDP, but it doesn't automatically lead to new ideas, better management, or improved skills. These are the things that actually increase output per hour across the entire economy. If the goal is steady growth that increases salaries and strengthens family life, then the focus should be on productivity, not just hours worked. Japan needs to change its approach and use policies that boost productivity. This can be done by focusing on skill development, improving management practices, adopting better ways to measure progress, and creating incentives that reward each hour of output. A slight change in how politics is conducted can lead to significant economic improvements in the long run. These improvements can be seen in companies, households, and government budgets.

Boosting Productivity in Japan: A New Way to Think About Work Hours

The most important thing is to stop focusing so much on hours worked as the main way to improve the economy. Too often, politicians assume that more time equals more value. This idea is easy to promote, and it leads to laws and policies that highlight effort. But when productivity per hour is low, simply adding more hours is not a good solution. The economy might produce more, but it comes at a cost to society. People's health suffers, they have less time with their families, and birth rates go down. These problems manifest as more doctor visits, fewer people starting families, and slower population skill development. To generate lasting growth, the message needs to shift from 'work more' to 'produce more per hour'. This shift opens the door for policies that target skills, management, and technology, which are the things that turn hours into real income.

When the problem is seen as a lack of hours, it also limits the possible solutions. If the main goal is to increase hours, governments might quickly change labor laws and tax rules. These changes are too broad. They might increase the total number of hours worked, but they don't change how people work every day. On the other hand, investments that change how work is organized may lead to lasting gains in productivity. Simple process changes, better scheduling, and small amounts of automation can reduce wasted time. They can also lower the number of mistakes and reduce the need to redo work. These improvements add up to marked gains in hourly productivity. Importantly, these changes are often affordable and can be easily reversed. They can be tested and then expanded. Focusing on hours makes it harder to test new ideas, as it favors simple solutions that don't account for differences across companies. Politicians should offer a broader range of options and fund the ones that are less risky but have the potential for significant returns.

There's also a political side to this. Supporting longer hours taps into cultural beliefs about duty and hard work, which are still strong. That's why some changes that extend legal working hours are popular. But the political conversation can be changed. Messages that connect higher output per hour with higher take-home pay and more free time can gain widespread support. Employers like policies that increase profit per hour. Workers prefer policies that allow them to earn more without sacrificing time with their families. Framing changes as a win-win situation reduces conflict and changes the bargaining process: companies invest in productivity to raise salaries, and workers accept changes because they get time back. Public campaigns that have promoted quality improvement and safety in other areas show that attitudes can shift quickly. A similar effort can shift the focus from working long hours to growth fueled by productivity.

Boosting Productivity in Japan: Skills, Management, and Measurement

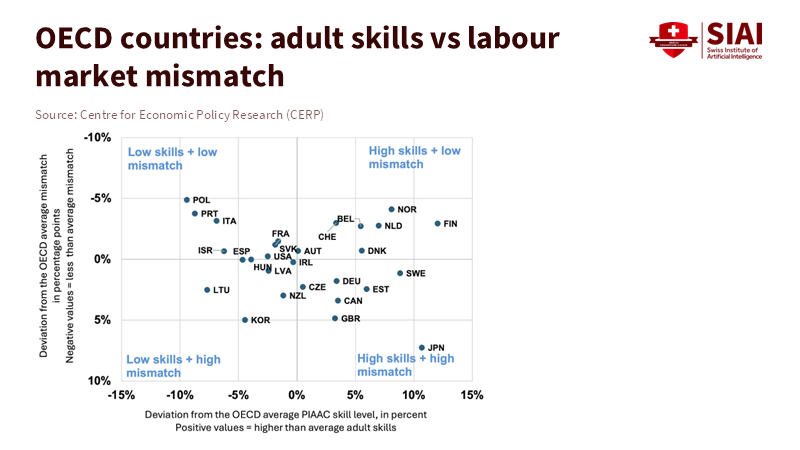

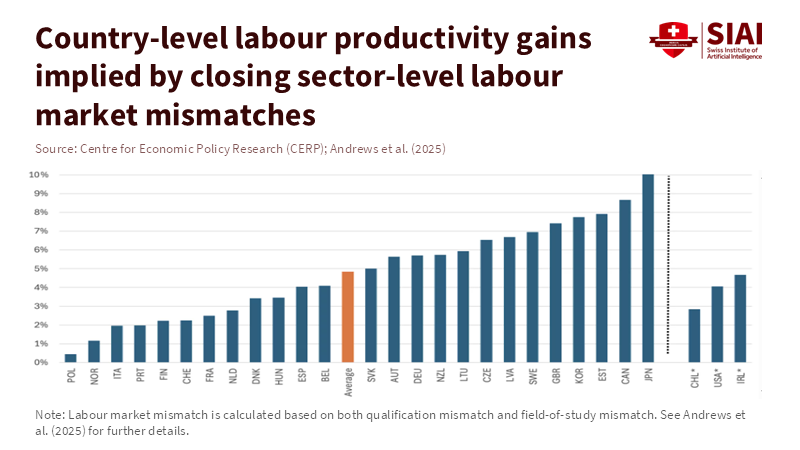

Skills are the first focus to increase output per hour. The Survey of Adult Skills shows that reading, math, and problem-solving are essential to productivity at the company level. Adults who can use data, follow digital processes, or solve everyday problems enable companies to adopt better tools and change roles with confidence. This leads to faster production, fewer mistakes, and higher-value services. The solution shouldn't be vague or apply to everyone. Instead, it should fund short, specific courses for adults linked to clear job outcomes. This means offering certificates in data use, basic automation, and process management. It also means involving employers by offering vouchers or shared funding that makes training driven by companies' needs, not just by what's available. Well-targeted adult learning quickly increases productivity per hour by providing the skills companies need most.

Management practices are the second focus, and they can often amplify the impact of other improvements. In many countries, simple routines such as daily checks, root-cause analysis, and precise measurements can significantly increase output. Many small and medium-sized businesses have a lot of knowledge, but they lack formal systems to share it. This results in irregular problem diagnosis, weak feedback within the company, and disorganized scheduling that wastes time. Public programs that subsidize short, practical management coaching have delivered significant returns elsewhere. They turn unspoken knowledge into repeatable processes without lowering quality. When managers learn to measure task duration, set clear daily goals, and coach employees to improve performance, the same workforce delivers more in the same time. Improving management is politically easier than broad deregulation because it keeps jobs while increasing competitiveness.

Measurement completes the set of three measurements that shape behavior. If official data and contracts reward total output but ignore output per hour, then policies will favor models that require more time. Changing the signal is essential. Better data on company-level productivity, shared in anonymous reports to managers, helps them see where to invest. Contracts that demand efficiency per hour create instant market incentives for productivity tools. Tax breaks that depend on pre-approved productivity tests align public cost with private gain. These steps also improve accountability: when subsidies are tied to measured outcomes, public money supports solutions that can be expanded rather than just symbolic actions. Public reports that present anonymous comparisons between companies encourage healthy competition and learning and make it easier for politicians to move beyond simple slogans.

Boosting Productivity in Japan: Policies That Actually Increase Output

Turning these three ideas into policy starts with small innovation grants for small and medium-sized businesses. Offer small grants for projects that redesign a work step or add a simple digital tool. Provide a brief plan and clear key performance indicators (KPIs) for the 6-month fund evaluation. Quick evidence builds confidence and encourages others to adopt the changes. Second, expand the use of employer-tied vouchers for modular adult learning. Vouchers reduce search costs and allow companies to buy the exact skills they need. Third, change tax incentives: accelerate depreciation for machinery that increases productivity and provide refundable credits for certified management programs to shift decision-making away from overtime and toward investment. Fourth, use contracts strategically: require measurable efficiency gains in major contracts. Finally, fund regional productivity centers that provide coaching, testing areas, and peer learning for small businesses. These centers act as go-betweens, turning best practices into local solutions.

There will be critics. Some will say small businesses can't handle change. Others will argue that older workers can't retrain. Both of these concerns can be addressed. Pilot programs in other developed economies show that small businesses adopt new tools when financial and technical barriers are lowered. Vouchers and small grants reduce early-stage risk. Training designed for adult learners, with flexible schedules, works for older employees. A second criticism is political: why not simply allow people to work more? The answer is that longer hours shift costs onto health and families. It's a social choice with long-term financial consequences. Encouraging investment that increases output per hour instead of reducing these hidden public costs. Seen this way, productivity improvements benefit both workers and businesses.

To be believable, changes must include precise monitoring and method notes. Measurement should use GDP per hour worked at the company or plant level when possible. Where company-level data is sensitive, anonymous comparisons and shared reports can be used. For training and grants, require simple before-and-after measures: baseline cycle times, output per shift, and defect rates. For contract-linked pilots, require suppliers to track time-to-complete per unit and report gains. These are realistic measurements. They are easy to collect and hard to manipulate. Policy design should be iterative: test, evaluate, publish the results, and implement changes that deliver real gains per hour.

To be specific, consider the numbers. Japan's hourly labor productivity was about $56.8 in 2023, while the OECD average was near $70 per hour; South Korea's figure was also low, in the low $50s. These statistics come from GDP per hour worked measured in purchasing-power-parity terms. These prominent figures show that Japan and Korea are well below high-performing OECD countries, and that even a small percentage gain would significantly change incomes. These simple facts make the case for targeted tests and quick evaluation.

For politicians, the math is simple and straightforward. A 20 percent increase in output per hour adds roughly $11–12 to every productive hour in Japan. If wages captured half of that gain, average hourly pay would rise by approximately $5–6, representing an immediate improvement for households. This calculation is just an example. It uses reported GDP per hour figures and assumes the increase is split evenly between labor and capital. It doesn't assume that the effects will be the same across all industries. Gains will vary. However, the main point is that small percentage improvements in output per hour translate into significant benefits for households and firms. That's why the policy options mentioned above, such as training, management coaching, targeted grants, and contracts, are essential for both economic and social outcomes.

The difference between Japan's output per hour and that of leading OECD economies isn't a reason to work longer; it's a reason to work smarter. Focused adult training, practical management coaching, measurement changes, smart contracts, and targeted financial incentives offer a realistic, politically feasible path. These policies allow workers to earn more without spending more time at work. They also reduce the social costs of overwork, including improved health, higher birth rates, and lower public spending on stress-related conditions. The government should test these ideas quickly, publish early results, and expand what works. Most importantly, the political message must change: a nation can grow by increasing what each hour produces rather than by simply asking people to spend more hours at the office. This change would bring both economic strength and better lives for the next generation.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Japan Institute for Labour Policy and Training (JIL). 2025. Current State of Working Hours and “Work Style Reform” in Japan. JIL Research Report. (Document analysing long working hours and trends in 2023 data.)

MK (Maeil Kyung / mk.co.kr). 2025. In terms of labor productivity comparison among member countries. MKニュース, 6 Jan 2025. (Analysis reporting South Korea hourly productivity in 2023.)

Nippon.com. 2025. Japan’s Labor Productivity Remains Low. 7 Jan 2025. (Summary and commentary on OECD GDP-per-hour figures for Japan in 2023.)

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2025. Cross-country comparisons of labour productivity levels. OECD Compendium of Productivity Indicators 2025. (Aggregate and country-level GDP per hour worked, PPP-adjusted.)

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2024. Adult Skills and Productivity: New Evidence from PIAAC 2023. OECD Publishing. (Report linking adult skill measures from the 2023 PIAAC to productivity outcomes.)

Comment