AlphaGenome and the Future of Science Education

Input

Modified

AlphaGenome is pushing education systems to rethink how AI, genomics, and policy are taught Predictive genomics now demands skills beyond traditional biology Without reform, the benefits will stay concentrated in a few institutions

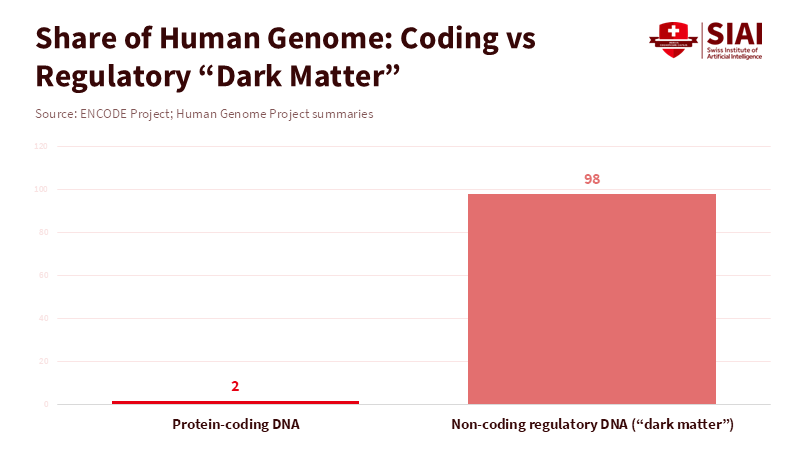

AlphaGenome can analyze a million DNA letters at once. It can also identify around 6,000 distinct signals in our genes related to how they're controlled, structured, and spliced. This isn't just a small step forward. This changes everything about how much computers can understand about the dark matter of our genome. That’s the 98% of our DNA that doesn't code for proteins. But it controls when, where, and how our genes turn on. For teachers and policymakers, this isn't just some small science story. This may shake things up, skills-wise. It affects the courses we teach and the science resources available to the public. It will determine who gains the benefits of a faster understanding of our genes and who is left behind. If schools and training programs continue to focus on outdated genetics and basic lab work, we as a society will lose the opportunity to use this effective tool to make healthcare fair for everyone, to use data ethically, and to help workers transition into new fields. We need to make significant policy changes. It's not simply about technical training; it's about rethinking civic duty, ethics, and how our institutions work. And we need to start right away.

AlphaGenome's dark matter: what it does and why it matters for learning

AlphaGenome is a highly sophisticated deep learning model. You give it a million base pairs of DNA, and it can predict all sorts of things about how genes work, right down to a single base. What that really means is that it can tell you how even tiny changes (just one letter) in a long stretch of DNA can affect how genes are expressed, how our DNA is structured, and how genes are sliced up in different tissues. The developers of AlphaGenome claim it can predict approximately 5,930 distinct signals in human DNA. It can also perform as well as or better than other existing tools in tests. These are some serious technical wins: analyzing a long stretch of DNA (a million bases) and being sensitive to each base pair have always been tricky balancing acts. AlphaGenome makes that compromise smaller. For teachers, here’s the main point: understanding genes isn't just about wet labs and textbook diagrams anymore. Computer models that can predict things are now key to discovery. If teaching doesn't include how to use procedures to understand how genes are controlled, the students who graduate will know the words but not the tools used in current research and therapy.

The second important thing for education is how we judge evidence. AlphaGenome is a tool for generating possible explanations. It helps us narrow down which areas to focus on in experiments. It doesn't replace actual experiments. This means students need both skill sets: they need to understand statistics, the degree of a model's specificity, and how to design experiments, all at the same time. Classes should show how predictions made by computers can be translated into lab tests and how to interpret model results with a bit of skepticism. Policies need to fund cross-subject lab projects that allow students to repeatedly test the models' forecasts. Without these real-world experiences, graduates might either trust the models too much or dismiss them as mysterious black boxes. Neither is suitable for public health or for science.

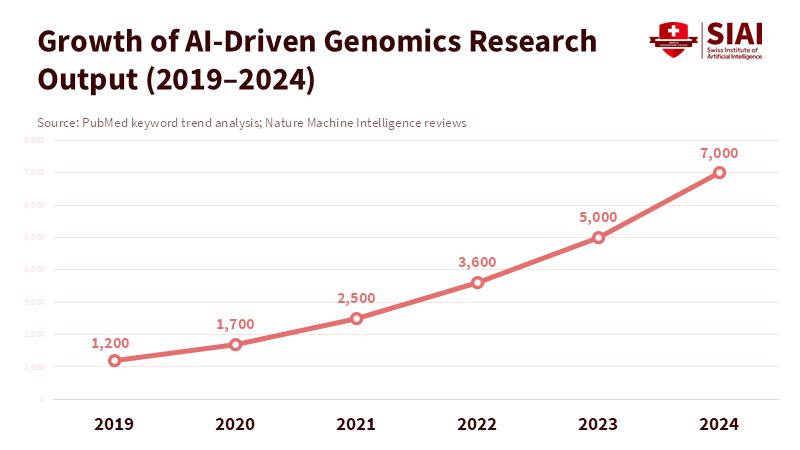

AlphaGenome's dark matter: workforce, credentials, and fair access

If predictive genomics takes off, we’re going to need experts who can work in both fields: people who can understand what the computer models are saying and turn that into action in clinics or in biology labs. Right now, college programs often treat bioinformatics as optional. That won’t be enough in the future. Policy needs to reexamine how we grant credentials so that knowledge of computational genomics becomes a key skill for biology, health, and data science programs. Schools should create short courses that award certificates in reading model results, assessing uncertainty, and designing experiments to verify results. These certificates would allow clinicians, lab technicians, and data analysts to improve their skills without completing a full degree program. That would also shrink the time between discoveries and when the workforce is ready to use them.

Fairness is another significant risk. Strong models trained on public data can accelerate research. But the rewards of that research tend to be concentrated in fancy labs, private companies, and leading schools. Places with limited resources might not be able to adopt AlphaGenome. So, the policy needs to provide subsidized computer access, public APIs, and explicit teaching materials, along with technical training. Government investment in shared computer resources, local bioinformatics centers, and teacher training can broadly build local skills. This isn't just charity. It's about lowering the risk. If only a few places control how genes are interpreted, then policies on health, agriculture, and monitoring will be based on a limited set of priorities rather than on broader public needs.

AlphaGenome's dark matter: curriculum, teaching, and ethics

What should we teach in a revamped curriculum? First, the basics of regulatory genomics: enhancers, silencers, how DNA is structured, and splicing. This should be taught by having students interact with models. Students need to learn how to read effect sizes and uncertainty estimates, run scans, and design simple lab tests to validate results. Second, computational literacy: handling sequences, evaluating models, understanding data sources, and basic systems for making research reproducible. Third, ethics and policy: how data is governed, consent for using genes to make inferences, the risk of bias in training data, and what all this means for insurance, jobs, and privacy. This last bit needs to be serious, not just a quick ethics module. We need to use real-world cases that connect model output to actual social outcomes.

How we teach matters. Hands-on labs where students suggest a regulatory variant, use a model to rank it, and then plan an experiment teach scientific thinking better than lectures alone. Having students assess each other's work and work in cross-subject teams is more like the real world. Policy can promote this by funding basic curricula, instructor fellowships, and open teaching modules that lower the barriers for universities and community colleges. It's essential that these changes be measurable: learning outcomes should track not just knowledge and the ability to turn predictions into testable questions, but also to think about the impact on society.

AlphaGenome's dark matter: governance, validation, and societal trust

A final policy area is outside of classrooms but depends on them: governance. AlphaGenome and similar tools accelerate variant ordering. That may lead to faster therapies, but it also raises the stakes for oversight. Regulators and institutional review boards need to update their assessments of research and diagnostic claims using models. That means we need new reviewers who understand model limitations. Training programs must specifically prepare candidates for oversight roles.

We need to expand our validation resources. Computational forecasts should be linked to standardized experimental data in public places. That means funding systematic efforts to test prioritized variants in cell types and conditions and to record when they don’t work. Public faith relies on tracking which predictions were validated and which failed. Schools and training courses can collaborate with biobanks and open science platforms to create learning environments that both teach and contribute to the validation of datasets. In short, teaching, research, and regulation need to be designed together so that model improvements benefit the public.

Toward an education policy for anticipatory genomics

The immediate steps are affordable. First, include short genomics-AI modules in biology and data science tracks. Second, fund instructor fellowships to help faculty redesign lab courses so students can run simulations and plan validations. Third, create regional compute grants and open API access to models so students and small labs can experiment without incurring high costs. Fourth, create micro-credentials that certify the skill to interpret model variability, design validation experiments, and assess governance hazards. These aren't just dreams. These are implementation choices that scale quickly with smaller investments compared with genome-scale experimental infrastructure.

Some people will argue that the program is already too comprehensive and that adding computational genomics will displace other important work. That's a fair point. However, predictive systems are changing what counts as core knowledge in molecular biology. Some may worry about ethical concerns: training more people in genomic interpretation might accelerate misuse or discriminatory practices. But the answer isn't to withhold training but to deeply integrate governance and ethics training into those curricula. Finally, some may argue that countries with small research budgets may not benefit much from this. That points to international coordination and shared computing resources, as well as funding models that support capacity building in lower-resource areas.

AlphaGenome’s ability to read a million DNA letters at once is a technical headline. But its real impact is on teaching and civic duty. The model compresses decades of lab work into computer flags that require human assessment, lab work, and public governance. Education policy shapes how that judgment is formed and how that follow-through is distributed. Governments and institutions should treat the AlphaGenome news as a reason to revamp curricula. Invest in training, expand validation resources, and combine technical upgrades with ethics and governance education. We’re not chasing every new model. We want to ensure that as predictive systems push the frontier, the workforce, the public, and regulators move together, ready to turn insights into public benefit.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Avsec, Ž., et al. (2026). Advancing regulatory variant effect prediction with AlphaGenome. Nature, Volume 649, Issue 8099.

DeepMind. (2025). AlphaGenome: AI for better understanding the genome. DeepMind blog.

Science Media Centre. (2026). Expert reaction to paper on Google DeepMind’s AlphaGenome.

Scientific American. (2026). Google DeepMind unleashes new AI to investigate DNA’s ‘dark matter’.

Comment