Freedom, Skills, and Growth: Why Human Capital and Democracy Must Be Recast as a Joint Project

Input

Modified

Democracy raises growth most where human capital is already strong Freedom and skills act as multipliers, not substitutes, in economic development Sustained prosperity requires joint investment in institutions and people

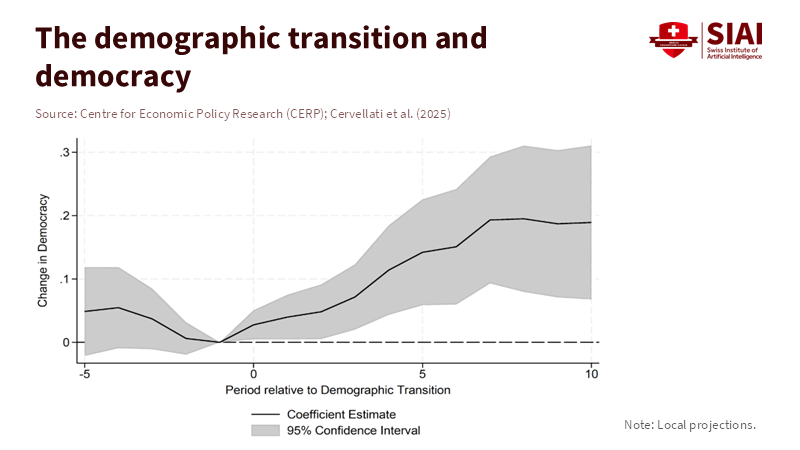

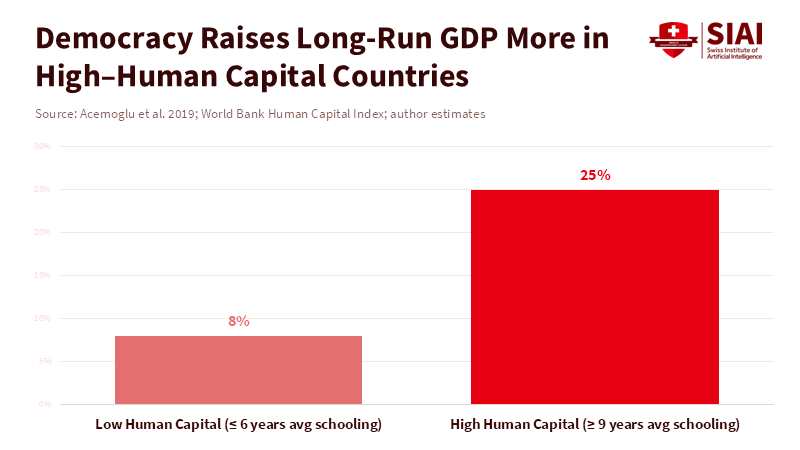

When a country becomes a democracy, its average income per person tends to go up over time—often by about 20%, according to many global estimates. But this general idea masks something important: the skill and health of the country’s people. Good studies show that when a country becomes a democracy, its income can rise by around 20% in the long run. Still, these gains are bigger and happen faster if most people already have a high school education and access to basic health care. At the same time, global data shows that many developing countries still struggle with education and health. According to research by Siddique and colleagues, better health outcomes in middle-income countries, such as higher life expectancy and lower infant mortality rates, are linked to stronger economic growth. This suggests that while freedom and free markets matter, a country's population's skills and health play a major role in shaping its economic success.

Rethinking the old debate on human capital and democracy

This isn't a disagreement between scholars looking at society and those focused on economic growth. Instead, it's a suggestion to rethink how we make policies. If a country becomes a democracy but doesn't plan to improve its people's skills and health, it won't see as much economic benefit. According to a report from the Atlantic Council, countries that invest in their people's education and health but lack political freedom may not achieve their full potential, as democratization has been shown to lead to significantly higher long-term economic growth than countries that remain autocratic. According to a report from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, democratic governments can play a significant role in fostering economic growth. The study found that countries transitioning to democracy saw their GDP rise by about 20 percent over 25 years, compared to what it would have been if they had stayed authoritarian. Both perspectives about the impact of government type on economic outcomes hold elements of truth. However, we need to go beyond simple cause-and-effect explanations and recognize that the relationship depends on the population's skills and health. Democracies encourage things like good schools and accessible health care. However, for real improvements in productivity, good-quality health and education services need to be accessible to everyone. If these are lacking, political freedom may offer civil rights but does not necessarily lead to widespread economic growth. According to research by Siddique, Mohey-ud-din, and Kiani, there is a strong link between better health, as reflected in higher life expectancy, and economic growth.

To be specific, current research shows that there are differences between countries. Large studies that have looked at many countries as they became democracies have found that their incomes often increase over time. Still, these increases are usually bigger in countries where people have more education and better health care. According to a study published in the Global Social Sciences Review, economic growth is closely linked to higher life expectancy and lower infant mortality, highlighting the importance of education and health as key contributors to a country's economic success. If a country lacks strong education and health systems, simply becoming a democracy might not immediately boost economic growth, since these factors act as important multipliers. They help markets and institutions turn political freedoms into economic gains. This means we shouldn't think of it as an either-or situation—either democracy first or economic growth first. Instead, both political freedom and the skills and health of the population need to improve together for a country to develop well.

According to Larry Diamond, most countries that transitioned to democracy around 1990 were middle-income nations, while almost all high-income countries were already democracies and few low-income countries made the shift, suggesting that wealthier societies have historically been more likely to sustain democratic systems. Yet, this isn't always the case. According to a study by Acemoglu and colleagues, countries that transition to democracy tend to see significant long-term increases in their GDP per capita, showing how political and economic progress are closely linked. While some nations can raise living standards without liberal politics and some democracies may struggle if they neglect investments in their people, the evidence suggests it is most helpful to view political and economic development as interconnected. When people are educated and healthy, democracy works better. According to a 2023 article, countries with higher levels of democracy tend to see improvements in child health outcomes, suggesting that responsible democratic governments are more likely to invest in health care and support well-being.

How Education and Health Affect the Economic Benefits of Freedom

Here's a simple explanation: When the rules are clearer and the political situation is more stable, businesses and entrepreneurs are more likely to invest in new things, use better technology, and expand their markets. However, these investments only lead to real results if workers have the skills and health to use them effectively. A factory with modern equipment won't be productive without trained technicians and managers.

So, when a country becomes a democracy, it creates more demand for skilled workers and more opportunities for them. But whether this leads to economic growth depends on how skilled and healthy the population already is and how quickly they can improve. Studies show that the long-term income gains from democracy are much larger in countries with higher levels of education.

We can see how important education and health are by examining various measures. The World Bank's Human Capital Index combines health and education to predict how productive workers will be in the future. According to Steven V. Miller, low-income democracies have experienced economic growth rates similar to those of low-income autocracies over the past 40 years, suggesting that even if two countries transition to democracy, their economic outcomes may not differ significantly. The country with a higher score on the Human Capital Index will usually see more investment, faster productivity growth, and fewer problems during the transition. That's why becoming a democracy without also improving education and health care often leads to political gains without the expected economic boost for everyone.

This also explains why some countries with autocratic governments have experienced rapid economic growth in the past. When a government uses its resources to improve education and health—through programs like mass literacy campaigns, industrial training, or public health initiatives—the economy can grow quickly even without much political freedom.

However, this kind of growth is fragile. Without political accountability, the benefits can be concentrated in the hands of a few, leading to inequality. Also, the progress can collapse if the government's policies fail. Democracies, on the other hand, have the systems in place to support long-term investments in education and health, as long as political leaders are motivated to spend money and make reforms that benefit the people. So, the goal shouldn't be to choose between democracy and investing in people, but to create a political system that makes these investments sustainable and inclusive.

What Policies Should We Prioritize? Combining Education, Health, and Freedom

If education and health make democracy more valuable from an economic standpoint, then our policies need to focus on two things at once. First, governments and aid organizations should consider education and basic health care as essential infrastructure, not just social programs. This means budgeting for actual learning results, not just how many kids are enrolled in school. It also means investing in health programs that support child development and keep adults productive.

Second, democratic institutions need to be set up to protect these investments from being affected by short-term political interests. This can be achieved through stronger local accountability, transparent budgeting, independent statistical agencies, and public oversight of education and health care services. That way, corruption becomes more difficult, and leaders are encouraged to support long-term programs.

What should government officials and leaders do right away? They should improve how we measure learning and fund programs proven to improve reading, math, and child nutrition. They should also strengthen support for teachers, vocational training, and continuous adult learning to help workers adapt to new technologies. Protect health programs that reduce child stunting and adult diseases, as these are strong indicators of how productive people will be throughout their lives in many low-income countries. These aren't just abstract goals; they involve specific budget choices that affect how private investments and public programs pay off. When governments combine these actions with transparent institutions and regular public input, the economy is more likely to grow sustainably.

There may be concerns that public spending on education will be wasted, inefficient, or used for political purposes. Others may point out that in some places, democracy has led to unstable policies that discourage investors. These are valid concerns. The solution isn't to abandon the strategy of investing in both democracy and education/health, but to design it with safeguards. These safeguards can include independent audits, community involvement, gradual pilot programs, and funding that is tied to measurable results. Evidence shows that when countries that are becoming democracies combine education improvements with clear measurement and accountability, learning outcomes improve and attract private investment. We need to be realistic about the challenges, but we shouldn't assume that we have to choose between democracy and effective public investment.

Democracy and economic growth don't have to be in conflict; they can work together. Their joint success depends on a third element: the skills and health of the population. The long-term income increase of around 20% that is often associated with democracy is real, but how large and how fast it occurs depends on education, health, and people's ability to take advantage of new opportunities. Policymakers need to stop thinking of political reform and investments in people as separate stages. The better approach is to improve both at the same time. Protect freedoms that enable accountability while expanding education and health programs that equip businesses and entrepreneurs with skilled labor. For educators, this means focusing on the quality of learning and lifelong skill development. For leaders and aid organizations, it means funding programs with clear measures and political safeguards. For policymakers, it means designing institutions that make investments in people sustainable over time. That's how freedom leads to productivity, and that's how rights lead to better lives.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Brookings Institution. (2024). Democracy is good for the economy. Can business defend it? Brookings.

LSE International Development Blog. (2024, July 25). The economic growth and democracy debate. London School of Economics.

Acemoglu, D., Naidu, S., Restrepo, P., & Robinson, J. A. (2019). Democracy Does Cause Growth. Journal of Political Economy.

Politico. (2024). Democracy declined for 8th straight year around the globe, institute finds.

World Bank. (Human Capital Project). Human Capital Index. World Bank Publications.

Comment