When Margins Shrink: The One-Person Company and the New Economics of Scale

Input

Modified

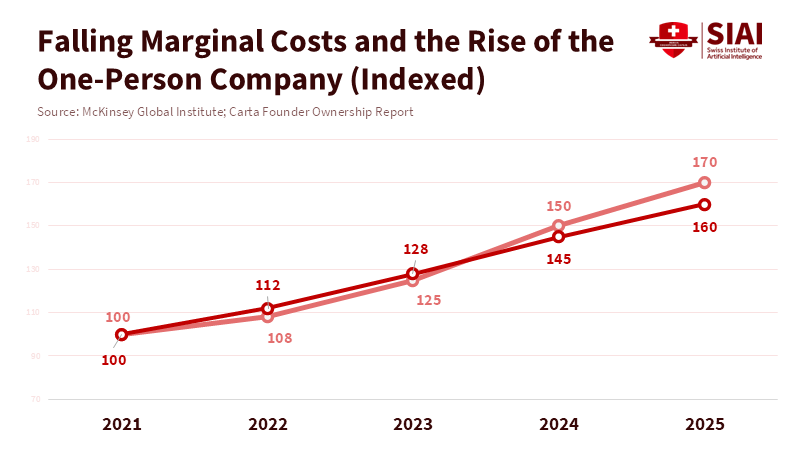

The collapse of marginal costs is enabling one-person companies to compete at scale AI and platforms are reshaping firm boundaries, productivity, and market structure Policy must adapt to support solo firms while limiting new platform bottlenecks

The rise of the one-person company is not just a minor trend; it signals a bigger shift. In 2024, about 35% of new startups on major private-capital platforms had a single founder, up from the teens just a few years ago. However, these solo firms still receive a much smaller share of venture funding. This pattern—more solo startups but less capital per founder—makes sense when the costs of producing and distributing goods and services drop. Lower costs remove the barriers that once required teams and upfront capital. As a result, more solo entrepreneurs are emerging, and the business landscape is changing: small, flexible providers can challenge established companies, niche products can reach global markets, and individuals can use AI, platforms, and outsourcing to increase their impact. This article asks a key policy question: as costs fall, how should regulators, educators, and funders help spread these benefits while preventing new concentrations of power?

How falling marginal costs birthed the one-person company

The main economic change is straightforward: when it becomes cheap to produce, monitor, and distribute products or services, it is easier for people to enter the market. In the past, high fixed costs like team coordination, physical infrastructure, gathering information, and customer support made it hard for individuals to compete, so teams and firms that could pool resources had an advantage. Now, digital tools and generative AI have reduced many of these costs to almost nothing. Tasks that once needed full-time specialists—such as content creation, coding, customer service, market research, or basic legal work—can now be done with ready-made tools or by hiring temporary contractors through online platforms. The cost of providing one more digital service or running a small marketing campaign is now very low, and supervision costs are dropping because automated systems and standardized workflows reduce the need for large management teams. For educators and policymakers, this matters because it changes who can compete and how value is shared in the economy.

This shift is more than just a new technology trend. Productivity increases in two main ways: first, new tools help individuals work faster and more efficiently; second, platforms and gig markets let individuals use services like payments, cloud computing, freelance design, and global marketing without having to pay for everything themselves. Together, these changes mean that many digital businesses no longer need large teams to get started. We can see this in the data on new startups and in the growing number of solo-run products and services that reach wide audiences without traditional payrolls. These lower barriers to entry should change how we teach entrepreneurship, how public funds support small businesses, and how regulators view market structure.

What the data tell us — productivity, funding, and market structure for the one-person company

The headline trends are clear and measurable. Surveys and market datasets show rapid adoption of generative AI inside organizations, and private-market datasets document a clear rise in solo founders among newly formed companies. Independent industry analyses estimate that generative AI alone can add trillions in productivity value across industries, which explains why an individual operator using those tools can be unusually productive. At the same time, investment flows show that solo founders still receive a smaller share of venture dollars per team, indicating that capital markets treat solo ventures as higher-risk or lower-scale bets. In sum, the statistics describe an economy in which capability is decoupling from capital: capability rises, but the incumbent financing architecture lags behind.

A short method note on figures: when I use published percentages and macro productivity estimates, I rely on recent industry surveys and private-market reports from 2023–2025; where data require aggregation across heterogeneous sources (for example, estimating the share of new firms that are solo-led), I use primary datasets from private markets research and corroborate them with independent sample surveys of adoption. Where precise totals are not reported, the narrative uses conservative interpolations and reports ranges rather than single-point estimates. The point of these checks is not to fetishize a single number but to ensure that the qualitative pattern—rapid capability gains for individuals, rising solo founding, and persistent capital gaps—holds across multiple data sources and assumptions.

Those patterns produce specific economic effects worth naming. First, competition intensifies at the low end of cost curves: a solo operator can supply a niche product at a fraction of the price of a legacy vendor because their incremental cost is lower. Second, market concentration can paradoxically rise even as entry increases: platforms that supply critical complements—hosting, payments, distribution, APIs—can garner outsized rents, since many one-person companies depend on the same few providers. Third, firm boundaries blur: a single operator can coordinate dozens of external contractors and automated agents, creating a virtual firm without a conventional payroll. For policymakers, this creates a dual challenge: how to preserve competition among suppliers while preventing new bottlenecks where a handful of platform providers extract monopoly rents or control essential data.

Policy for a world of one-person companies

Policy should stop trying to force a vanished past into the present. Rules built on the assumption that firms must be multi-person entities—tax rules, labor rules, or small-business supports geared to payroll—will miss most of the action. Instead, three practical policy reorientations are urgent. First, update small-business support to recognize capability rather than payroll. Grants, procurement set-asides, and training programs should be accessible to verified solo operators; eligibility metrics might shift from payroll thresholds to revenue, client diversity, or digital capability proofs. Second, rewire competition policy to focus on platform choke points. If many one-person companies rely on the same cloud, data marketplace, or AI-training pipeline, regulators should examine whether those platforms lock in suppliers or extract rents through non-transparent pricing and data appropriation. Third, redesign workforce and education programs to equip individuals with the hybrid skills that matter: product literacy, data hygiene, contract management, and the ability to supervise and audit automated agents.

There are clear implementation steps. Procurement systems can open micro-contracts that require less administrative overhead and pay quickly. Public digital infrastructure can offer authenticated identity and reputation signals so buyers can trust solo suppliers. Small, staged financing—like revenue-based loans or matched procurement credits—can replace blunt VC expectations for scaling. Meanwhile, competition agencies should look beyond market share numbers. They should map how many suppliers depend on a single API, marketplace, or payment rail, and how fragile that dependency is. These are not theoretical fixes, but practical, pro-competitive moves that reflect the new reality: firms can be lean but globally effective.

Anticipated critiques are predictable. Some will say solo scale is a bubble, and that the productivity gains are fragile. They may argue teams are needed for quality, resilience, and long-term innovation. Others will worry that more solo work leads to precarious jobs and weaker labor protections. Both critiques deserve policy responses. The first critique calls for careful measurement: not every solo product will last, so funding and procurement should reward traction, not hype. The second critique means we need modernized protections: access to health benefits, portable retirement accounts, and stronger collective bargaining for platform-based workers. These changes can separate protections from payroll but keep flexibility. In short, we should not block the one-person company. Instead, build institutions that make solo work productive and fair.

When marginal cost falls, markets rearrange themselves. The rise of the one-person company is an expected outcome of lower production costs, better monitoring, and richer platform complements. That reality offers an opportunity: a more diverse supplier base, lower prices for consumers, and new routes to self-employment. It also poses risks: new bottlenecks, fragile business models, and social protections that lag technology. The right policy response is not nostalgia for mid-20th-century firm structures but a pragmatic redesign: broaden access to public procurement and micro-finance, protect solo operators with portable benefits, and guard against platform concentration with dependency-focused antitrust tools. If regulators, educators, and funders act with calibrated speed, we can channel the productivity unlocked by lower marginal costs into broader, more resilient prosperity rather than let it concentrate in a few gatekeepers. The opening pattern holds: fewer dollars for more founders, higher individual output, and a fundamentally new shape to firms. Our job is to shape institutions that serve that new economy, rather than pretend it never arrived.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Ashley, M. (2025, February 17). The Future Is Solo: AI Is Creating Billion-Dollar One-Person Companies. Forbes.

Chui, M., et al. (2023). The economic potential of generative AI: The next productivity frontier. McKinsey & Company.

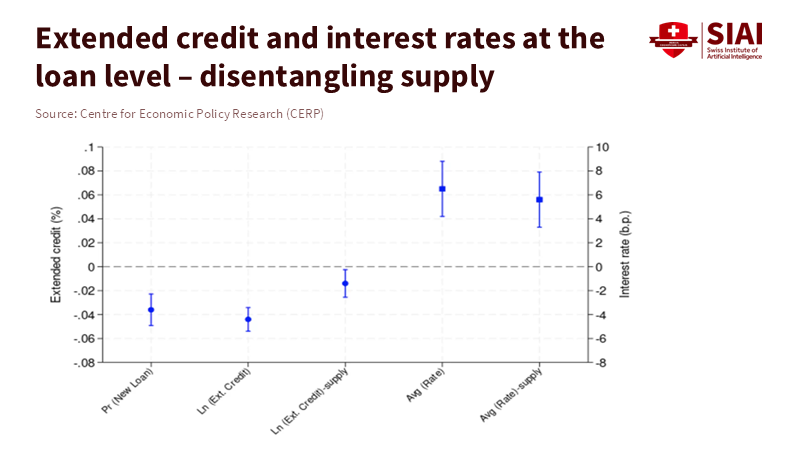

D’Andrea, A., Pelosi, M., & Sette, E. (2025). When broadband comes to banks: Credit supply, market structure, and information acquisition. Journal of the European Economic Association. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeea/jvaf041

Founder Ownership Report. (2025). Founder Ownership: Data on founding teams and equity (2015–2024). Carta.

Investopedia. Bell, E. (2025, March 8). How small businesses can use AI tools. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/how-small-businesses-can-use-ai-tools-8609366

Medium. Cher, T. (2025, Aug 13). The Rise of the One-Person Unicorn: How AI is Redefining Entrepreneurship. Medium.

Comment