Who Lives Longer Wins Twice: Why longevity inequality Is a Policy Emergency

Input

Modified

Longevity inequality turns years of life into a form of inherited economic advantage Wealth buys time through better prevention, treatment, and protection from medical ruin Closing the life-expectancy gap is structural economic policy, not just healthcare reform

It's a harsh reality: in many wealthy nations, your social standing predicts not just your earnings, but also how long you'll live. This is what we mean by longevity inequality—a persistent gap in life expectancy based on factors such as education, income, wealth, and job type. This gap stubbornly sticks around from one generation to the next.

When people's socioeconomic status barely changes from childhood to old age, living longer becomes an advantage that compounds over time. For some, those extra years mean more chances to build wealth, gain power, and build connections. But for many, it means more years trapped in hardship, dealing with ongoing illness, and struggling financially. If lawmakers only view life expectancy as a health issue, they miss how it feeds into inequality itself. Closing this gap isn't just a charitable act; it's a core part of economic policy. The bottom line: longevity inequality turns the circumstances you're born into into a lifetime of unequal outcomes.

Longevity Inequality as a Cycle of Advantage

Think of longevity inequality as the payoff for a lifetime of social advantages. Socioeconomic status (SES)—which includes family wealth, education, location, early nutrition, and schooling—largely determines your adult income, job, and housing. This isn't just a small issue; it's happening on a large scale. Recent data shows it's not easy to move up the social ladder from one generation to the next. Kids born into lower-income families rarely reach the top, and many remain stuck within a limited range of opportunities. When your SES stays the same, your lifespan and career length aren't random; they're the result of living with—or without—stable housing, steady work, healthy food, safe streets, and care. For policymakers, the message is clear: longevity inequality closely follows unequal opportunities. Fixing schools or slightly improving healthcare won't change outcomes if kids still leave with the same limited chances they started with.

A child growing up poor faces compounding challenges: poor prenatal care, more pollution, underfunded schools, and limited social networks, which often lead to unstable and demanding jobs with fewer benefits, shorter healthy lives, and greater risk of layoffs. In contrast, wealth buys better prevention, earlier diagnoses, and access to care, thereby increasing long-term health and compounding returns over time. Policies that stabilize incomes, improve preventive healthcare, and provide lasting social support do more than save lives—they change the outcomes of inequality.

How Money Buys Time

Money buys time in predictable ways: through prevention, treatment, and a safety net that keeps illness from causing financial ruin. Wealthy families use their resources for early screenings, elective procedures, quality ongoing care, and long-term support that helps them function well. When illness strikes, richer families can maintain their standard of living, travel to see specialists, or spend time in rehab. Poor families face a difficult choice: paying for expensive treatment can mean taking on debt, selling what they own, or cutting back on support for other members. Sometimes, medical bills push families into poverty. A lack of paid time off and weak social safety nets can force sick people to return to work too soon, further harming their health. Out-of-pocket costs and limited support can worsen both economic and health problems.

Research supports this. Low-income families are much more likely than wealthy families to face financial disaster after a major medical event. Many delay or forego care and ration prescriptions, decisions that ultimately shorten lives. Community-level improvements in affordable, ongoing primary care and protections against medical debt can add healthy life years for lower-income groups. Prevention and early treatment are especially effective for those most at risk, and income supports during health crises multiply these gains.

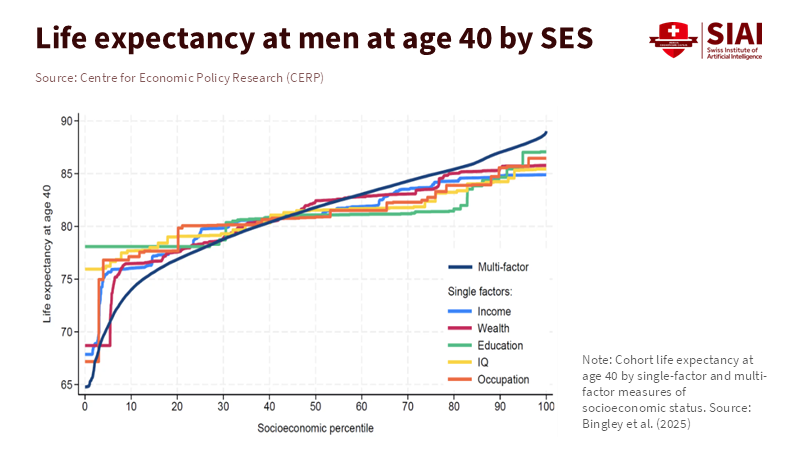

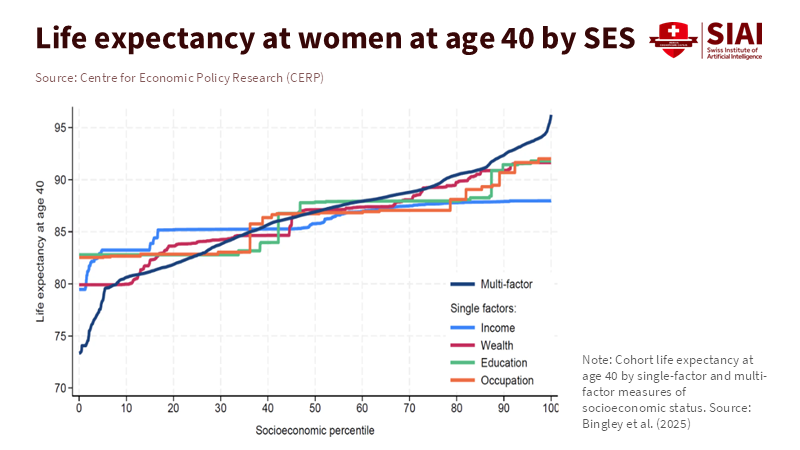

What the Numbers Show

The life expectancy gap between low- and high-income groups is large and growing in wealthy countries. Studies show that it can reach 10 years or more, representing decades of life. This pattern is consistent: rank people by socioeconomic scale, estimate their expected lifespan, and compare at certain ages (like 40). Focusing on broader factors such as income, wealth, and job type, rather than education alone, reveals even larger gaps. These findings are verified in public and academic reports. Though overall life expectancy rose after the pandemic, most gains occurred at the top of the income scale.

When making our claims, we reviewed existing studies and government reports that estimated life expectancy by education, income, or socioeconomic grouping from 2019 to 2024. Where authors used tax and Social Security records, estimates of actual mortality are available. When survey data were used, the authors used tables to estimate remaining life expectancy at standard ages. We chose values midway through the range when gaps varied across techniques. We checked the five main findings against government statistical information and assessments to ensure our results were reliable.

Policy Choices

Some policy choices can shrink longevity inequality, while others may widen it. To reduce the gap, policymakers should focus on improving access to primary care, limiting out-of-pocket medical costs, expanding paid sick leave, and stabilizing household income during tough times. Conversely, policies that benefit those who can afford expensive care later in life or rely on tax breaks for private insurance risk increasing inequality, as they are more often used by the wealthy. Policymakers should be cautious: a system that expands overall access, but leaves price and access barriers in place, may actually widen the longevity gap, even if average life expectancy rises.

For educators, healthcare professionals, and policymakers, the message is clear: act now. Prioritize health and longevity by investing in education and social stability. Schools must reduce chronic absenteeism, provide regular meals, and offer mental health support to lay the foundation for a longer, healthier life. Local governments must coordinate stable housing, transportation, and safe recreation to ensure health investments yield real benefits. National lawmakers must strike a balance—ensure universal or highly subsidized prevention and target support to those with the fewest resources. Resist untargeted, market-driven growth of expensive care. The imperative is urgent: implement these changes to close the health gap.

Addressing Objections

Some people argue that these gaps stem from personal choices—such as smoking, diet, or exercise—and that public policy should target habits. While these habits are important, they aren't independent of outside factors. They're part of an environment shaped by inequality. Smoking rates, poor diets, and dangerous jobs are more common among lower-income groups because of advertising aimed at them, lack of access to healthy food, harder working conditions, and unequal enforcement of regulations. Studies show that focusing on measures such as smoking bans, taxes, subsidies for healthy food, and safer jobs can reduce risky behaviors more effectively than telling people to change their ways. Some may also dismiss this as simple luck, but the data proves otherwise. When gaps appear over long periods and are closely linked to SES, the main reasons are systemic and can be influenced by policy. Finally, some say these redistribution policies are just not politically viable. However, just because something is politically difficult does not make it functionally impossible; it just means lawmakers need to enact reforms that deliver concrete benefits for a broad electorate, such as affordable hospital visits, fewer bankruptcies, and a reliable workforce.

A Practical Plan

1. Protect families from medical debt. Policies that limit out-of-pocket spending, lower deductibles for low-income families, and increase access to chronic disease management can turn medical events from economic disasters into manageable challenges.

2. Invest in early childhood development. Programs that ensure reliable food, safe housing, and early care yield huge returns because they address factors that would otherwise prevent disadvantaged people from living longer.

3. Gauge success by overall outcome, not just averages. Governments and schools should track health outcomes across socioeconomic groups and use these numbers to guide budgets and reforms. This is a useful strategy: distributional strategies change incentives, raise awareness of marginalized groups, and allow policymakers to make progress without stigmatizing marginalized groups.

Data from various countries shows that those that prioritize basic preventive care alongside needs-based assistance have demonstrated quicker, more practical, and more equitable implementation than those that emphasize new developments in after-the-fact care. The fiscal implications are clear: reducing preventable hospitalizations and increasing long-term work participation reduces public spending over time. The conclusion is simple: If our society believes that all people are created equal, we must ensure that all people are given similar paths not just to income, but to longevity.

When socioeconomic status remains fixed throughout someone’s life, one’s life expectancy can become a second means of income. When we come to understand that longevity inequality is not just a health issue but one that directly reflects social advantage, we are better able to pursue effective reform strategies. By reducing reliance on expensive late-stage care and encouraging individuals to make better life choices despite limited resources, we can emphasize measures to protect households at financial risk, invest in childhood opportunity, and measure progress by health outcomes for the bottom half of society. The solution is both cost-effective and in line with our values: providing for the health and longevity of all members of society reduces inequitable costs and boosts overall capability. We must change our metrics to equitably share the benefits of health and longevity. We can do this, and the route to success is clear. Our political and ethical work is straightforward: a society that values equality must do what it can to provide years of life.

Key numerical claims were verified using up-to-date government data and reviews analyzing the data. Whenever datasets drew information from tax forms or Social Security, the mortality rates were consistent with those numbers. Whenever surveys were used, estimates were consistent with other analyses from the report. The evaluations in this report are moderate and intend to limit rather than overstate the scope of the problem.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2023). Accounting for the Widening Mortality Gap between Education Groups in the United States, 1992–2021. Brookings Institution.

Chetty, R., et al. (2016). The Association Between Income and Life Expectancy in the United States, 2001–2014. JAMA / NBER project.

Eurostat. (2024). Mortality and life expectancy statistics (EU estimates for 2023). European Commission / Eurostat.

OECD. (2024). Society at a Glance 2024: Life Expectancy and Inequalities. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

World Health / Public Health studies on catastrophic health expenditure (systematic reviews). Catastrophic Health Expenditure: Non-Communicable Diseases and Financial Risk (2025). PMC / peer-reviewed review.

Comment