When Cheap Money Stops Working: Why the Zero Lower Bound no longer revives Europe’s economy

Input

Modified

High public debt is weakening the power of the zero lower bound in Europe When fiscal credibility erodes, lower interest rates no longer guarantee stronger growth or stable inflation Europe must rebuild fiscal space and institutional trust if monetary policy is to work again

Global public debt has increased to $98 trillion, representing about 94% of global economic output in 2023 and 2024. This massive debt changes things. Remember when we thought low interest rates could always get the economy moving? That idea doesn't hold as much water anymore. It's not just an abstract number; it messes with how things work. When countries owe a lot, changes in interest rates have a greater effect on their budgets. This raises questions among businesses and markets about whether the government can continue to support the economy. You can see this happening in Europe. Although interest rates have declined, banks are lending less. Investment isn't growing as much as it should, and demand for goods and services is weak. The preferred solution after 2008 – keeping interest rates near zero, buying up government bonds (quantitative easing), and even trying negative rates – worked well for about ten years. Those days when cheap money automatically boosted the economy? That's the end. This is extremely important for schools, universities, and government offices that are planning for the future, assuming low rates will always suffice.

The Zero Lower Bound: What It Did in the 2010s

The zero lower bound refers to the point at which interest rates are already at or near zero. It doesn't leave central banks much wiggle room to lower rates. In the 2010s, those in charge developed some ways to address this. They used those near-zero rates and purchased many assets. They also sought to inform everyone that they would keep rates low for a long time. In some places, they tried negative interest rates.

These actions did a couple of things. First, they lowered the cost of borrowing all across the economy. Second, they shifted expectations. By saying they would keep rates low and buy bonds, central banks pushed long-term interest rates down and encouraged investors to take more chances. The results seemed good for quite a few years. According to the Global Debt Report 2025, governments and companies significantly increased their market borrowing after the financial crisis, with global debt reaching 25 trillion US dollars in 2024, nearly three times the level in 2007. People expected some inflation, but not too much. In Europe, this approach helped stabilize banks and maintain functioning government bond markets. Governments sought to stabilize their finances after the crisis. The idea was simple: cheap money raised asset values, which improved everyone's financial situation, giving them more money to spend. This made people feel that the central bank could address issues even when the government lacked much flexibility.

The playbook of the 2010s was based on the idea that businesses and people would spend more if borrowing was cheaper. There was substantial evidence that this was true. Central banks conducted studies, reviewed corporate financial records, and examined outcomes in countries where investment increased after they stabilized their finances. According to research published in VoxEU by Abildgren and Kuchler, when banks in parts of Europe began charging companies for holding deposits due to negative interest rates, many firms responded by increasing their investments in fixed capital and hiring more workers. The key point was that central banks could credibly commit to keeping rates low for an extended period. This promise made long-term interest rates fall. This meant that the actions worked through the financial system, not just through the central bank's own actions.

Why Lower Rates Aren't Working in Europe Anymore

The last few years have shown a significant problem: when countries have substantial debt, the financial consequences of any interest rate changes become uncertain. If a country has high debt, its interest payments increase substantially when long-term interest rates rise. This changes expectations. If businesses and individuals anticipate higher taxes, spending cuts, or political instability, lower interest rates won't make them feel secure. According to the International Monetary Fund, public debt in Europe rose sharply due to the pandemic and energy shocks and remains elevated compared to pre-pandemic levels. Obtaining a loan became more difficult for many companies. So, the lower rates didn't lead to more borrowing or faster economic growth.

Two things explain this. First, when debt is high, changes in interest rates affect the government's budget. When central banks lower interest rates to boost the economy, this also lowers the returns on government bonds. This can lead to concern about inflation and higher taxes. Markets and large companies respond by retaining cash or delaying investments. Second, things have changed since 2010. The economy isn't growing as fast, there's more risk in the world, and the financial markets aren't as connected as they used to be. All of this has made investment less sensitive to changes in interest rates. In Europe, for instance, investment in buildings and equipment slowed down in 2023 and 2024, even where interest rates were low. Banks lending less money in late 2024 was not a minor matter. It meant there wasn't enough money available for companies to borrow, even though the central bank was trying to make it easier. Basically, the cheap money ran into a wall. The financial system was fragile, and the economy was less responsive to price changes than it used to be.

This situation isn't the same everywhere. The United States and Japan have different financial systems and histories. They also have high public debts. However, the way Europe is structured – with a single central bank but many countries with their own budgets – exacerbates the problem. Because there's a single interest rate policy for everyone, large debts in some countries increase overall risk. This makes it harder for the central bank to have the same effect on everyone. If lower interest rates produce different financial and market effects across countries, the idea of cutting rates to boost the economy is less effective. This has consequences beyond just the economy. It changes how policy is perceived. When markets don't believe that rates will remain low for long, the central bank's promises become less effective, and expectations become more volatile. Instability is harmful to decisions involving the long term, such as hiring personnel and investing in equipment.

What Officials and Teachers Need to Do

First, we must accept that monetary policy can’t be the only solution to economic problems. This isn't giving up; it's just being realistic about how to use our efforts. For countries with large debt burdens, the priority should be financial systems that are credible and don't hinder development. It’s more important to be believable than to be fast. Markets need to see a plan that demonstrates debt is manageable. In Europe, this means better coordination. This includes shared investment in green energy and digital projects, clear rules that enable support during economic downturns, and contingency plans for when countries face financial stress. Such actions improve the financial perspective.

Second, we need to focus on the obstacles that monetary policy can’t fix. Education budgets, training programs, and research funding aren't just handouts; they're investments that make the economy more responsive to change. So, schools and universities need to act fast. It's dangerous to freeze hiring or delay projects, assuming the economy will bounce back soon. Schools and other institutions should focus on programs that boost productivity and increase skills. This could mean teaching skills that local companies need. This means short training sessions. They could also establish partnerships between universities and industries to turn research into things that can be sold. These actions improve over the long run and make it easier to reduce the debt.

Third, rethink central banks' and finance departments' strategies to address interactions. This involves creating rules and communication that produce smaller changes in public costs from short-term bond returns. Examples include longer-term issuance programs, variable-rate debt instruments, and debt management departments. This also requires planning for public investment, with central banks and governments agreeing on a sound investment plan. For schools, designing programs with finance ministries, tying funding to clear employment results, and using joint funding helps markets read as productive. Policy should then shift to forward structural partnerships.

Finally, expect and refute the primary evaluation: overestimating the impact of unconventional monetary moves. Central banks have tools that help during crises. However, it doesn't result in credibility. If sovereign debt has a significant impact on their financial performance, then its deployment incurs costs and becomes financially burdensome. Some investments may reveal stronger returns at lower rates. The argument is growing in scope. It still gives fiscal credibility, targeted funding, and supply-side reformation.

Cheap money helped when debts weren't too high, and the financial system was working well. The $98 trillion in global public debt indicates something different. In this new situation, the zero lower bound creates a coordination issue in financial markets. The solution for educators and decision-makers has a practical structure: reestablish credibility, directly invest, and frame those investments as growth-boosting rather than risky. We can't depend on lower rates to produce development.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Altavilla, C., Burlon, L., Giannetti, M. and Holton, S., 2019. Is there a zero lower bound? The effects of negative policy rates on banks and firms. ECB Working Paper Series No. 2289. Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank.

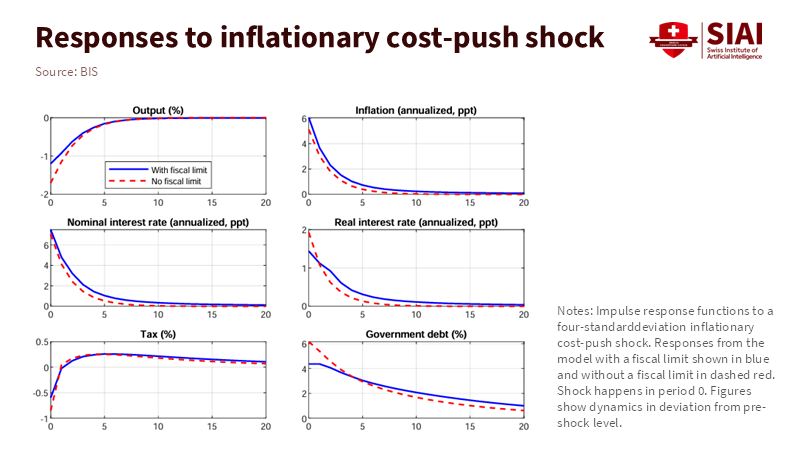

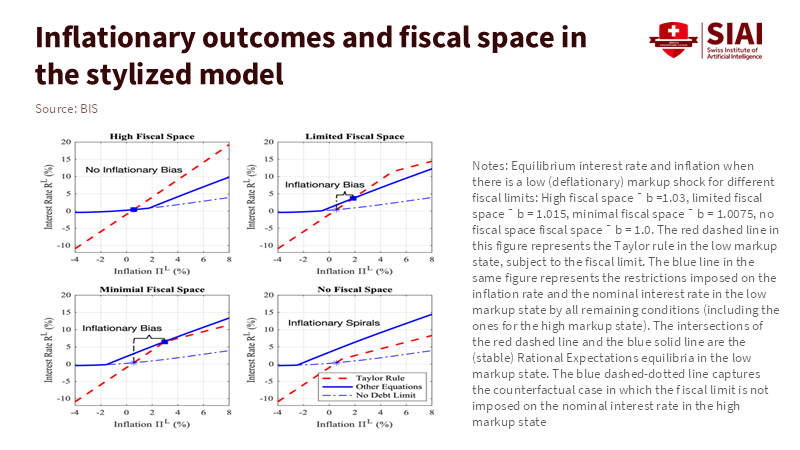

Bank for International Settlements (BIS), 2026. The perils of narrowing fiscal spaces. BIS Working Paper No. 1328. Basel: Bank for International Settlements.

European Central Bank (ECB), 2024. Euro area bank lending survey: Fourth quarter of 2024. Frankfurt am Main: European Central Bank.

European Investment Bank (EIB), 2023. Investment Report 2023/2024: Resilience and renewal in Europe. Luxembourg: European Investment Bank.

Eurostat, 2026. Government debt statistics for the euro area. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

International Monetary Fund (IMF), 2024. Global Debt Monitor 2024. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Sumner, S., 2021. The Princeton School and the Zero Lower Bound. Mercatus Center Working Paper. Arlington, VA: Mercatus Center at George Mason University.