Maximizing Agentic AI Productivity: Why German Firms Must Move Beyond Adoption and Teach Machines to Act

Published

Modified

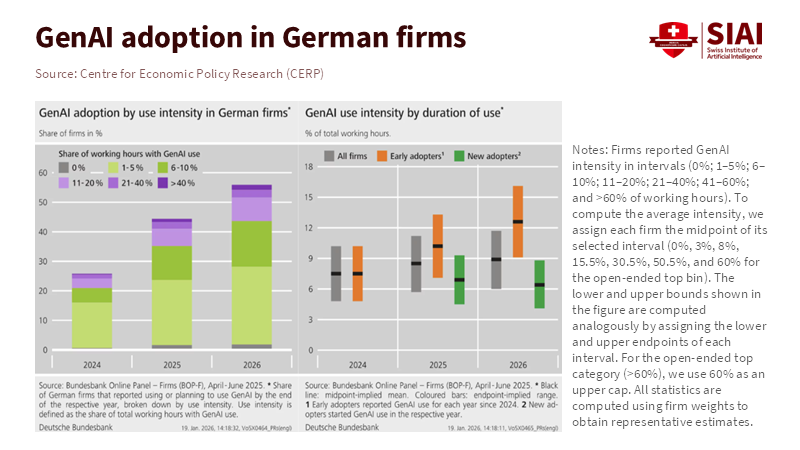

German firms adopted generative AI fast, but productivity gains are flattening The next phase is converting adoption into durable agentic AI productivity Education and policy must shift from tools to systems, governance, and measurement

It didn't take long for generative models to get into businesses. However, the speed at which they were accepted conceals something: the initial positive results aren't as strong as they were. When a company says it uses AI, it could mean anything. It could be a simple chatbot test or a complete system that plans, executes, and learns across various tasks. The important point is that the number of companies that moved past the test stage into routine AI use has increased significantly since 2023. However, the additional output per euro spent is lower than it used to be for those who started using it early on. This means we're not talking about whether we should use AI anymore; we're talking about turning it into something useful. We need to translate general use into something specific and ensure that experiments lead to lasting improvements. If schools, colleges, and politicians see all companies as the same, they won't recognize that companies that have already widely used AI need different kinds of support. They don't need more introductions, but they do need assistance with changing their systems, measuring results, and managing things. In this way, AI can deliver consistent benefits. We call this agentic AI productivity. It's about AI systems that not only create things but also act reliably in complex businesses, increasing output over time.

Agentic AI Productivity and How We Need to Think About It

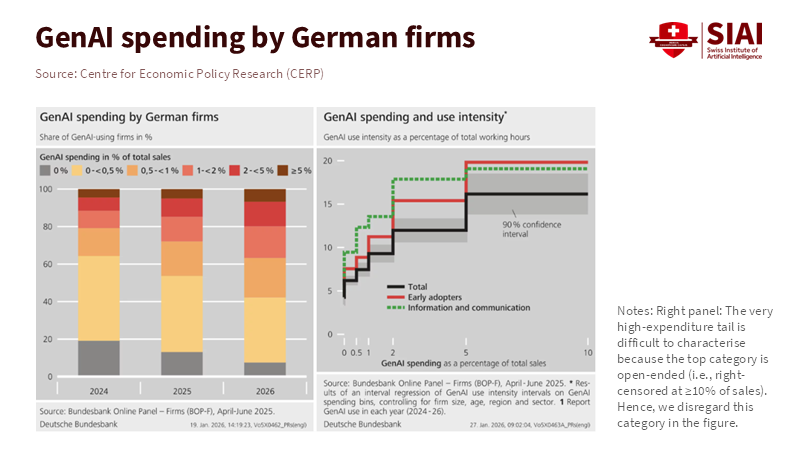

We need to stop focusing on how many people are using AI and start focusing on the benefits and what businesses are learning. The number of people using generative tools is important because it indicates how many companies have adopted them. However, it doesn't say much about whether companies are getting real value. Evidence shows that many German companies are using it widely, but the performance gains for each additional euro spent are decreasing for companies that already use the tech. This is a sign of saturation: early users get the easy benefits, but getting more requires bigger changes.

This is important for education policy because the skills and support that helped develop rapid tests differ from those needed to scale AI systems. Workers need to know how to write prompts and keep data clean. Also, they need to know how to work with machines, measure AI performance, and ensure explicit guidelines and feedback. Teaching people to use the tools at a basic level won't change their productivity. The big challenge is teaching people to change how they work so that AI becomes a helpful partner that reduces waste, prevents mistakes, and increases what can be done across jobs.

Early tests focused on drafts, summaries, and prototypes. But using AI regularly needs measurements of process value, for example, shorter times across teams, fewer mistakes, and better decisions when things are uncertain. These things are harder to measure, but they're the only way to know if it's still worth spending more money. Companies that focus solely on basic metrics might report early gains that later fade. In short, using AI is now a basic requirement. What will make companies successful is measuring and managing AI productivity.

Proof of Saturation: Germany, Companies, and Returns

From 2023 to 2025, German companies moved quickly from experimenting to using AI regularly. National surveys show a big jump from low adoption in 2023 to much higher numbers the next year. But it's happening at two speeds: many companies report some use, but only a few are using it deeply and regularly.

Growth in the number of companies using AI is important. But independent reviews and company surveys show that the benefits aren't as high for those who started using AI early: spending more money doesn't yield as many gains as it did at first. This suggests that as companies use AI in many areas, the simple gains, like automating text, getting data, or making reports, are used up. Improving later requires changing jobs, combining models with work systems, and changing management.

The impact on policy is clear. If German companies reach a point where simply getting more people to adopt AI isn't enough, then the incentives that drive adoption are outdated. What's important is support for redesigning processes, public resources for measuring AI outcomes, and teaching people to think strategically and manage. These are big changes. They require time, cross-departmental leadership, and new courses in schools and colleges that teach how to set goals, define AI actions, and evaluate results. Without these things, greater use of AI will spread resources too thinly and increase costs without increasing real output.

Italy's Households and Slow Adoption: A Comparison

Compare the saturation in German companies with what's happening with households in Italy. Surveys in Italy show people know about AI systems but are slower to use them regularly, and even slower to use them in daily tasks. Surveys show that about 30% of adults have tried generative tools in the past year, but only a few use them monthly or in ways that change how they work or study.

Households face various challenges, including limited digital skills, restricted access to technology, and concerns about risks and privacy. This makes them careful about using AI. The result is a double contrast: companies adopt AI quickly and then reach a limit, while households adopt it slowly and may never use it properly without support.

For politicians and teachers, the Italian example shows that more access doesn't mean more productive use. For households, learning should start with basic skills and progress to understanding how to work with AI. Schools and adult learning programs need to teach people how to manage AI tools, check results, and make ethical decisions about what to allow AI to do. If not, the social gap will widen: companies that use AI will gain a competitive advantage, while households and small companies that rely on them will fall behind, and inequality will worsen.

From Tests to Systems: What Companies and Schools Must Teach

Turning AI into real gains needs five changes inside companies. Each change affects how teachers train workers. First, move from knowing how to use tools to knowing how to design together. Create workflows where AI and people share goals and feedback. Second, include measurement in how things are done. Focus on process results, not just output numbers. Third, allocate time to management and testing to ensure AI behaves reliably in new situations. Fourth, focus on data and protected links so models can act with accurate information. Fifth, create roles for people who turn strategy into AI instructions. These changes are as much about teaching as about tech. They require courses that combine tech with business design, people skills, and ethics.

Schools and universities need to change quickly. They need to offer courses that teach how to write goals, measure the effects of AI actions, and set limits for AI. Teaching needs to be hands-on: learners should design and run tests that measure gains from small changes. Short programs should teach managers to recognize when increased spending isn't worth it. Also, government policy can help by funding partnerships that enable small businesses to measure results and by supporting benchmarks that let firms compare AI outcomes without disclosing private data.

Addressing Criticisms and Providing Rebuttals

Two common criticisms will come up. First, critics will argue it's too early to discuss saturation because many firms still don't use AI. This is true overall; many small companies are behind. But the policy needs to differ across firms. A general push to increase use misses the firms that need change. Second, some will say that AI is unsafe and we should limit it. That's a valid worry, and it supports our main point. If AI is to operate autonomously, management, testing, and measurement are essential. Stopping AI is not the answer. A better policy supports safe use by funding research, requiring reporting of problems, and promoting test environments in which AI behaviors can be tested before widespread use. Evidence shows that regulators and companies can work together to create standards that allow safe use while protecting people.

Another argument is about how we're measuring things. Critics will say that surveys can't capture long-term results, so claims about benefits are just guesses. That's a fair point. Our view is that the available evidence suggests that benefits decrease after a quick start. We support that claim with different data, along with caution. In cases where direct measurements are missing, policy should concentrate on improving measurement rather than giving large, untargeted support. Companies and governments need to agree on measurements for AI outcomes so we can judge investments.

We are at a turning point. The first push of generative tools changed what companies tried. The next must change how they work. The key is not whether a firm uses AI but whether it can get benefits as investments increase. That's what we mean by AI productivity: systems that act, learn, and improve in ways that raise output for each euro spent. German firms are showing signs of saturation. Italian households show slow adoption. Both facts point to the same conclusion: stop treating use as the goal. Support measurement, management, business design, and teaching about how humans and machines work together. Those are the things that will turn experiments into permanent value. Time is short, and the choice is clear. Support organizations and teach the skills that enable AI to improve work rather than break it up. Doing nothing will give us more tools, more noise, and smaller gains for the same cost.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements (2025) Exploring household adoption and usage of generative AI: New evidence from Italy. BIS Working Papers, No. 1298.

Centre for Economic Policy Research (2025) Generative AI in German firms: diffusion, costs and expected economic effects. VoxEU Column.

Eurostat (2025) Digital economy and society statistics: use of artificial intelligence by households and enterprises. European Commission Statistical Database.

Gambacorta, L., Jappelli, T. and Oliviero, T. (2025) Generative AI, firm behaviour, diffusion costs and expected economic effects. SSRN Working Paper.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2024) Artificial Intelligence Review of Germany. OECD Publishing.

Comment