The Limits of Financial Coercion: Why a US Treasury Sell-Off by One Power Would Backfire

Input

Modified

Selling US Treasuries hurts the seller first by lowering the value of what remains Only coordinated action by major holders could move markets, and that coordination is unlikely US Treasuries function as a shared stability asset, not a usable financial weapon

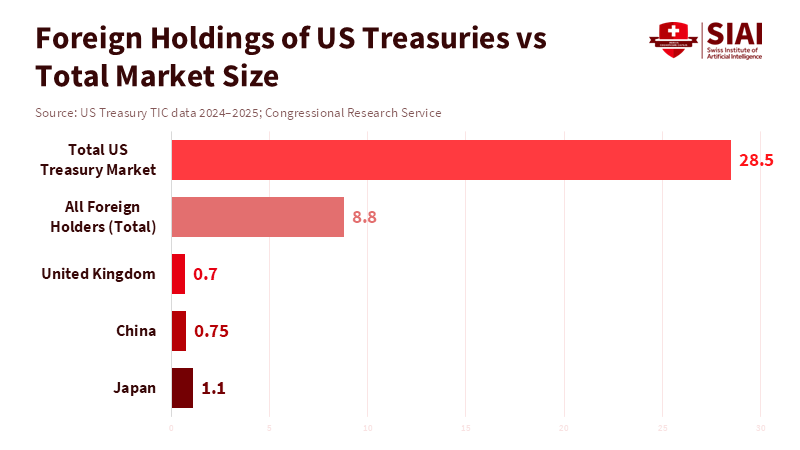

It's often said that foreign countries could hurt the U.S. by dumping their holdings of U.S. Treasury securities. These holdings are estimated to be around $8–9 trillion. It's important to understand that this money isn't sitting in one big pile. Instead, it's spread out among different governments, financial institutions, and investment funds worldwide. The idea of a country hurting the U.S. by selling off its Treasury bonds might seem tempting at first glance. However, the way financial markets operate makes this very difficult. If a large holder of Treasury bonds suddenly tries to sell them all at once, the price of those bonds will drop. This means that the bonds the seller still owns are now worth less. Plus, it hurts anyone else who holds those bonds. Instead of gaining an advantage, the seller ends up harming themselves and everyone else involved. The decision to use Treasury bonds as a weapon is constrained by several factors: the market's math, the market's structure, and the political motivations of the countries involved. The real danger arises only if several major holders of Treasury bonds coordinate to sell them over an extended period and are willing to accept the financial losses that accompany it. This would be like creating an OPEC for causing financial trouble – a group of countries with very different interests and political systems, which makes it very unlikely to happen.

How a Treasury Sell-Off Affects the Market

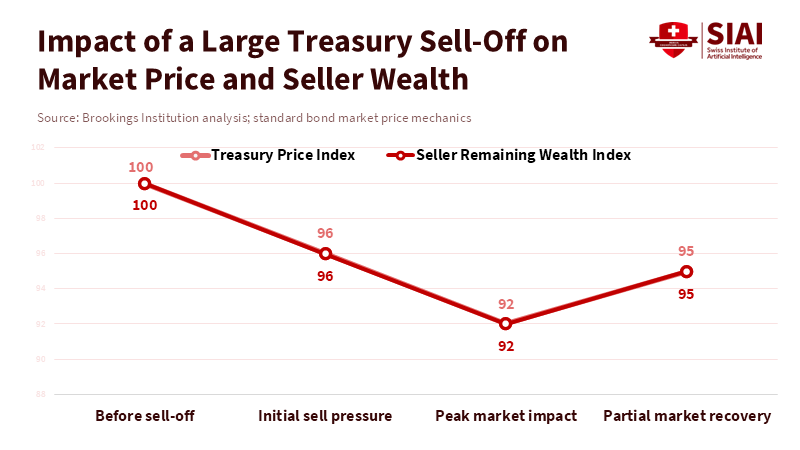

The way prices change in the market is simple: when a large holder sells a large number of Treasury bonds, the supply increases sharply. This causes prices to decrease and interest rates to go up. Anyone who still holds Treasury bonds will see their value decline. This is a problem because central banks and government funds hold Treasury bonds as part of their national wealth and reserves. A quick sell-off would cause the seller to lose money directly. It would also make it more expensive for the United States to borrow money. However, the higher interest rates don't necessarily mean the seller wins. In fact, the seller loses the most because it has the most bonds revalued at a lower price. Selling off Treasury bonds to hurt the U.S. is like hurting yourself. The market will punish the seller the most.

This isn't just a theory. The way trading desks operate makes it difficult to sell large amounts of bonds simultaneously. When a central bank sells a large quantity of bonds, it doesn't all hit the market at once. Instead, dealers, brokers, and the Federal Reserve create buffers that help absorb sales activity. The Federal Reserve can intervene by buying bonds as a last resort, or it can provide other measures that reduce price volatility. Even if the Fed doesn't take action, the selling pressure spreads through different levels of the financial system, where other buyers, both foreign and domestic, step in when interest rates become attractive. These buyers include private institutions that often make purchases through financial institutions in other countries. The result is that a large sale triggers a rapid price adjustment, which discourages the seller from continuing.

Why Threats from a Single Country Don't Work

Let's look at who actually holds these Treasury bonds. Japan, China, the United Kingdom, and a few other countries hold the most significant amounts. However, even their holdings are small relative to the total Treasury market, which is valued at $28–30 trillion. This is important because even if a country's holdings seem large, they remain small relative to the overall market. If a country like Korea or Taiwan tried to sell its bonds aggressively, prices would fall. This would reduce the value of their remaining holdings and might cause other countries to retaliate. Other holders might react by buying bonds at lower prices, thereby stabilizing the market, or by selling their own bonds to protect themselves. Either way, the country trying to cause trouble would not achieve its goal.

The political situation also makes a unilateral threat less likely. Treasury bonds aren't like personal investments. They are part of a country's national balance sheet and affect its overall financial stability. In democracies, leaders must answer to voters for any losses resulting from their decisions. A significant drop in value would show up in public records, official reserves, and pension funds. This makes the political cost higher than a simple strategic calculation alone.

Moreover, it's difficult for countries to coordinate their actions. Unlike oil, where producing countries share a common way of supplying the product and a reason to make money, Treasury bonds are held for safety, liquidity, and financial stability. There's no genuine shared interest in reducing the value of these bonds, as that would destroy a crucial international asset on which everyone relies.

Possible Scenarios and What They Mean for Policy

If a coordinated sell-off were to occur, the consequences would be felt worldwide. Interest rates would rise sharply, global borrowing costs would increase, and the value of the dollar could fluctuate unpredictably. But coordinated action is unlikely for several reasons. First, the costs to each country would be immediate and significant. Political leaders would have to justify losses that reduce national reserves, harm financial institutions, and potentially weaken their own currency. Second, coordinating such an action would require shared institutions and transparency, which don't exist among reserve managers. There's no system in place like the one used by cartels in the oil market. Third, there are few alternative investments that offer comparable scale and liquidity. To succeed in hurting the market by selling off Treasury bonds, a country would need to find buyers with matching financial resources, which are not readily available.

For educators and policymakers, the key is to have a balanced view. It's easy to think of Treasury bonds as a simple tool for political influence. But that ignores the way markets work and overestimates a country's ability to use its financial reserves as a weapon. It's essential to teach students that financial leverage is a two-way street and that the stability of safe assets depends on mutual trust. Governments should ensure their financial systems are strong. Central banks and finance ministries should continue to diversify their reserves for long-term stability. Still, it's essential to understand that changing investments shifts risks from one area to another. It doesn't guarantee a win in a financial conflict.

Policymakers should also focus on defensive measures. Transparent and open reporting reduces the risk of miscalculation. Swap lines, emergency funds, and collaboration through international organizations can act as buffers that weaken the impact of sudden sales. Regulators should ensure the financial system is strong enough to handle large cross-border transactions. Finally, public communication should be reasonable and avoid exaggeration. Calling Treasury bonds a weapon can create panic and distort prices. Instead, explain the trade-offs and the shared costs of destabilizing actions.

Addressing Common Objections

A large holder of Treasury bonds could still break the market by selling enough of them. While this is theoretically possible, it's not practical for the reasons mentioned earlier. To cause lasting damage, the seller would have to accept a significant decline in the value of their remaining assets. This is not a small price to pay.

Another argument is that secondary transactions and third-party custodians obscure the true extent of a country's holdings, leading public figures to underestimate the leverage a country can exert. There's some truth to this: custodial channels can make it difficult to see who really benefits from these holdings. But hidden exposure works both ways. It increases uncertainty for everyone involved and makes aggressive moves more politically risky. Policymakers avoid uncertainty. Uncertainty magnifies risk and creates market instability, neither of which is in anyone's interest.

Some believe that changes in technology or regulations could alter the situation. For example, if a group of large holders used derivatives or synthetic short positions, they might create unbalanced exposure. However, derivatives require collateral and counterparty credit risk. A large synthetic bet would quickly trigger margin calls and collateral requirements in a crisis, increasing losses for the initiator—the more complicated the method of coercion, the greater the operational risk for the attacker. Modern finance's complexity is a clumsy tool for political coercion.

Lastly, consider the importance of the dollar. The global payment system and many trade agreements still rely on the U.S. dollar. Undermining that asset through coordinated sales would not only raise U.S. interest rates but also disrupt global trade. This is a bad trade for countries that depend on dollar liquidity for exports and import financing.

The idea of using Treasury bonds as an easy weapon doesn't hold up under examination. Market forces punish those who sell abruptly. Political leaders don't want to undermine their own economies. The complexity of the financial system and the dollar's global role make coordinated action expensive and unlikely. That doesn't mean Treasury bonds are unimportant in global politics; it just means that this weapon is limited. Policymakers and educators should focus on building resilience, strengthening market infrastructure, clarifying reserve reporting, and investing in diplomatic channels. The safest approach is to strengthen shared institutions that would make collective harm too expensive to consider. Mutual dependence encourages caution.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Brookings Institution. “If China Stops Buying our Debt, Will Calamity Follow?” Brookings, 2009.

Central Bank Policy Research (CEPR). Europe’s US holdings: leverage lies in marginal demand. VoxEU / CEPR Policy Portal, 2024.

Financial Times. “China’s holdings of US Treasuries fall to lowest level since 2009.” Financial Times, 2024.

MarketWatch. “Foreign investors bought more Treasury bonds in February, official data shows.” MarketWatch, Feb 2025.

Reuters. “Why China won't 'weaponize' its US Treasuries stash.” Reuters, 29 Apr 2025.

U.S. Department of the Treasury. “Treasury International Capital (TIC) Data: Major Foreign Holders of Treasury Securities,” TIC data tables, Dec 2024–Feb 2025.

U.S. Department of the Treasury. “Treasury International Capital Data for December,” press release, 18 Feb 2025.

U.S. Congress, Congressional Research Service. “Selected Statistics on Foreign Holdings of Federal Debt,” CRS report, Dec 2024.

Comment