The Third AI Stack Is a Hope, Not a Strategy: Why Europe and Korea Can’t Catch an entrenched US–China Duopoly

Published

Modified

The third AI stack is a political ambition, not an industrial reality China’s open-source push wins users, not hardware supremacy Europe and Korea must focus on interoperability and skills, not full-stack rivalry

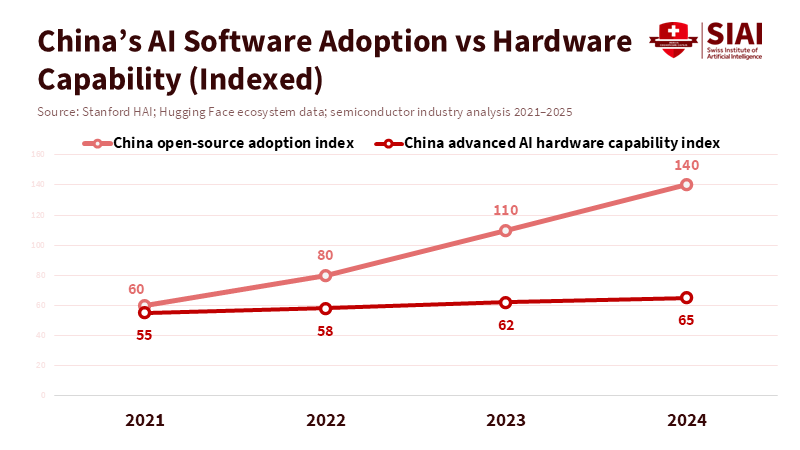

Between August 2024 and August 2025, Chinese open-model developers accounted for roughly 17% of global Hugging Face downloads—surpassing U.S. developers for the first time. That single data point captures a truth and a misreading at once: China has achieved scale in open-source and community adoption, but scale in downloads is not the same as an independent, competitive compute and platform stack. The talk of a third AI stack—a European or Korean alternative that will sit beside the U.S. and China—mixes aspiration with wishful thinking. Open-source diffusion buys influence and the breadth of users. It does not automatically produce the high-performance silicon, the global cloud infrastructure, or the developer lock-in that underpin dominant AI platforms. If decision-makers and instructors in Europe and Korea make strategy from comfort, they will misread the extent of capital, talent, and time required to translate downloads into durable industrial power.

Why the "third AI stack" is a mirage

When we refer to the third AI stack, we mean a self-sustaining, region-led combination of hardware, software standards, and large-scale cloud services that can engage global customers and developers independently of U.S. or Chinese ecosystems. That is a very high bar. Building it requires three mutually reinforcing assets at an industrial scale: advanced silicon, a large installed base of high-end cloud nodes, and widely adopted developer tools and runtimes. Europe and Korea have pockets of strength—excellent researchers, healthy public funding, leading semiconductor firms in Korea—but they lack the simultaneous depth across all three pillars. Export controls and supply-chain frictions have altered incentives. The U.S. controls high-end GPU exports and has layered licensing reviews, slowing the direct flow of the world’s fastest inference hardware; this constrains some Chinese compute access but does not erase the huge lead that proprietary GPU frameworks and optimized software stacks already enjoy. Those controls alter incentives but do not shrink the technical gap overnight.

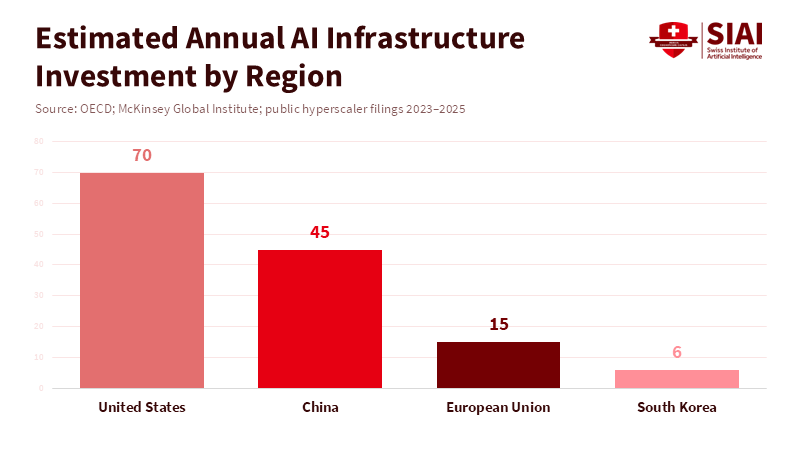

Capital matters more than rhetoric. To catch up after a decade of lag requires orders of magnitude more investment than typical national AI grants provide. Training the largest models needs sustained petaflop-years of compute and the advanced interconnects and memory hierarchies that only a few vendors can supply. Korea’s chipmakers can and do make excellent GPUs for consumer and embedded markets; competing at datacenter-class AI compute needs sustained foundry access, advanced packaging, and validated software toolchains that are expensive and time-consuming. Likewise, European cloud operators can focus on sovereign clouds and regulation-friendly offerings, but winning global developer mindshare requires low friction, competitive pricing, and a thriving community-driven ecosystem—things that privilege incumbents with broad scale. In short, the gap is structural, not simply financial or political.

Finally, we should separate user-facing openness from platform control. China’s success in open-model downloads shows how well governments and firms can seed ecosystems when proprietary hardware is constrained. But hosting, inference, and production deployments still congregate where performance, reliability, and developer convenience converge. Until an alternative stack meets those baseline expectations on cost and latency, enterprises and researchers will keep one foot in the U.S. or Chinese ecosystems, and hedging will win over wholesale migration.

How China’s open-source play reshapes the “third AI stack” narrative

China’s open-weight push is clever and consequential. By freely releasing model weights and encouraging derivative works, Chinese firms have multiplied global usage and created an optics advantage in the Global South and among developers who prize openness. That movement is not trivial: an ecosystem of lighter models, efficient condensation techniques, and developer tools can make AI useful inside constrained settings. This becomes a form of platform-building that competes on accessibility rather than raw exaflops. The result is a two-track competition: one axis is the top-tier compute race; the other is broad-based software adoption. China leads the latter. That matters for standards, formats, and the flows of talent and data that shape long-term software interoperability.

But this competitive win has limits. Open models need inference capacity to power commercial services at scale. When the highest-performance accelerators are absent or restricted, the economics and latency of large-scale services change. China’s response has been to develop indigenous chips and high-volume data center capacity. Early chips are serviceable and serve many workloads well, but independent analyses suggest they lag top-tier Nvidia chips in raw throughput and capability—sometimes by margins that matter for the most demanding training and inference uses. The engineering deficit combines node-level performance gaps with deficits in software maturity: compiler toolchains, distributed training orchestration, and optimized kernels are hard to replicate quickly. Engineers can reduce gaps over time, but these gaps interact with supply chains and standards in ways that compound the incumbent's advantage.

Another realistic implication: China’s open strategy has bought it a different kind of influence. If Chinese models, libraries, and runtimes become the de facto norms in many emerging markets, they shape developer expectations and institutional procurement. Europe and Korea can still set rules about data governance, privacy, and ethical uses. But norm-setting without compatible infrastructure is incomplete. The countries that combine standards with market-simulacra—deployable clouds, certified hardware, and developer incentives—will have more leverage. The open-source approach gives China a broad base from which to project standards through use; it is not yet a claim on high-end performance, but it is a claim on adoption and default formats.

Policy choices for educators, administrators, and policy makers in a US–China duopoly

Educatorshave to adapt curricula to the new terrain. Teaching neural network architecture without hands-on experience on modern accelerators is increasingly theoretical. Universities and vocational programs should prioritize access to a mix of cloud credits that expose students to both leading commercial stacks and popular open-source stacks used in real-world settings. That means negotiating partnerships to rotate cloud access, funding GPU hours for labs, and building coursework that evaluates compromises between performance and cost. Policymakers should treat computer access as infrastructure—like labs or telescopes—rather than an ephemeral grant. Subsidizing access to testbeds, investing in software toolchains, and underwriting open benchmarking projects will have outsized returns compared to one-off research grants. When students learn to optimize for latency and cost on real hardware, they graduate with industrially relevant skills rather than abstract knowledge.

Administrators and procurement officials face a choice matrix. They can double down on national sovereignty—buying local hardware and mandating local deployment—or pragmatically hedge by instrumenting multi-cloud and multi-stack interoperability. The latter is the wiser posture. Insisting on a pure “third AI stack” that isolates education systems and public services risks lock-in to immature platforms that will carry higher long-run operating costs. Instead, public institutions should require interoperability layers, fund open benchmarks, and sponsor translator tooling so models and datasets can port across stacks. That approach safeguards the regulatory agency while keeping operational performance within tolerable bounds. It also creates an exportable product: governments that can demonstrate safe, portable, and efficient AI deployments will have a stronger voice in global standards negotiations.

We must also face hard political-economic questions. China’s decision to prefer domestic stacks is a deliberate infant-industry strategy. If those domestic engineers succeed, the global configuration shifts; if they fail, China will still have bought time for its software standards to entrench in pockets of the world. Either outcome imposes costs and benefits on education systems. For universities and think tanks, the practical implication is clear: invest in cross-sectional analysis and applied deployments now. Trial projects that benchmark similar services on different stacks, publish the methods and results, and teach students to reason about trade-offs. In short, convert geopolitical uncertainty into a pedagogical advantage.

From wishful thinking to workable strategy

The third AI stack continues as a compelling political slogan. It promises national autonomy and dignity. It will not, however, spring into being because leaders declare it. The evidence is simple: open-model downloads are a form of influence but not an immediate substitute for exascale compute, top-shelf hardware, or mature software stacks. Europe and Korea can and should aim for partial sovereignty—investing in secure clouds, supporting open toolchains, and training engineers across multiple stacks—but the clearer path to impact lies in pragmatic interoperability, targeted industrial investment, and educational reform. We should treat compute and developer access as public goods, not prizes to be hoarded. That means real budgets for testbeds, transparent benchmarks, and curriculum revisions that privilege operational competence. If policymakers act with that realism, educators will graduate learners who can move between stacks rather than waiting for a mythical third column to appear. The world will be safer and more plural if alternative stacks grow by winning customers with clear trade-offs, not by political proclamation. The opening statistic matters because it highlights where influence is currently accumulating; our job now is to convert that influence into durable, responsible capacity—practically, cheaply, and with an eye on standards, not slogans.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Chin, C. L. (2026). Standards are the new frontier in the US–China AI competition. East Asia Forum.

CSIS. (2025). The limits of chip export controls in meeting the China challenge. Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Financial Times. (2025). China leapfrogs the US in the global market for 'open' AI models. Financial Times.

Hugging Face / Stanford HAI analysis. (2025). China's diverse open-weight AI ecosystem and its policy implications. Stanford HAI briefing.

International analysis of chip performance. (2025). The H20 problem: inference, supercomputers, and US hardware. Independent analysis.

Reuters. (2026). NVIDIA AI chip sales to China stalled by US security review. Reuters.

Comment