Market Value of a Degree: Why Learning — Not Logo, Now Pays

Input

Modified

The market value of a degree now depends more on skills than prestige Employers pay for verified, job-ready learning Education policy must validate outcomes, not labels

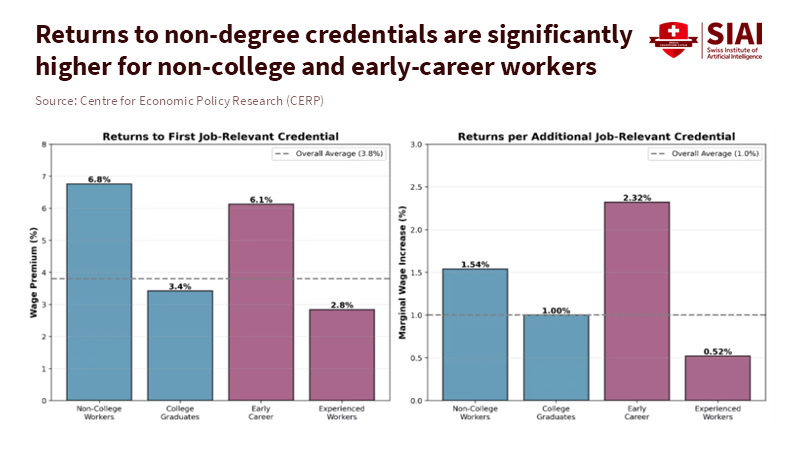

The worth of a college degree is changing quickly. It used to be that a degree from a well-known school was a sure sign that someone had learned valuable skills. But now, companies are more interested in what people can actually do on the job, not just where they went to school.This change is essential because the salary boost you used to get from going to a top-tier university can now be matched, or even beaten, by shorter training programs that focus on specific job skills. Obtaining a certificate that demonstrates proficiency in a specific job can increase pay by 3-7%, and even more for those who are newly starting or those without a degree. So, the question for schools and government isn't just Is college worth it? But which schools can prove they're teaching the skills employers need? The future value of a degree will depend less on the school's reputation and more on whether the skills learned can be verified and are helpful to employers.

What's Changing: Degrees vs. Skills

Let's look at the common idea that a degree from a top university is valuable for three reasons: (1) the students are smarter, (2) the teaching is better and gives you practical knowledge, and (3) the school has a good network to help you get a job. A report by Matthew Bone and colleagues notes that employers are increasingly adopting skill-based hiring practices, especially for AI positions, placing greater emphasis on demonstrable skills, such as those shown through projects or certificates, rather than simply favoring degrees from top schools. This suggests that instead of focusing solely on protecting the reputation of prestigious institutions, it may be more critical to start verifying and certifying what students actually know and can do.

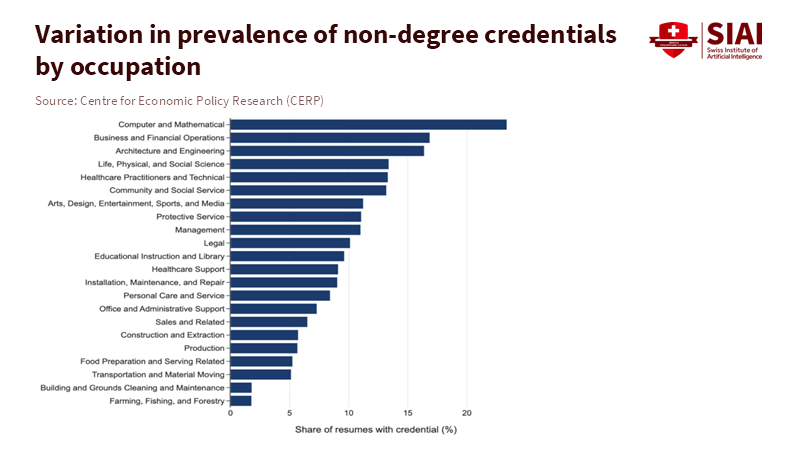

New information suggests that a school's prestige isn't the whole story. Looking at millions of resumes, training programs that aren't degrees can increase your pay if they teach you skills that employers need. One study examined more than 54 million certificates and approximately 37.7 million resumes in the U.S. and found that earning a certificate for a specific job skill was associated with a 3.8% increase in pay. The increase was even greater among individuals without a bachelor's degree or those early in their careers. This suggests that employers are paying for skills, not just a big-name school.

At the same time, studies of students who attended elite colleges indicate that their career success is attributable to the caliber of students the school admits and the connections they have with top companies, rather than to the teaching they receive. In short, a prestigious degree can help you get into certain high-level positions. But when it comes to hiring and pay for most jobs, skills that you can prove are becoming more and more critical.

What the Numbers Say About a Degree

To make good decisions about education, we need data and clear ways to understand it. I'm using three primary sources: (1) looking at lots of resumes and certificates to see how they relate to wages for specific jobs, (2) checking the results of short training programs like bootcamps and certificate programs, and (3) following people over time to see how their degrees affect their earnings. Each of these has its limits, but together they give us a good picture of what's going on.

By looking at resumes, we can see which certificates are standard for certain jobs, such as JavaScript certificates for software developers. We can then compare the wages of people with those certificates with those of people without them, while accounting for factors such as location, experience, and degree status. If a certificate is relevant to a job, having it is usually linked to a pay increase. For people without a college degree or those just starting, the pay increase is even bigger. But having lots of certificates unrelated to your job doesn't help. It's about having the right skills for the job. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, as educational attainment increases, people tend to have lower unemployment rates and higher earnings, which supports these findings drawn from an extensive analysis of records using computer programs. Where causation was challenging to determine, I reported results conservatively, for example, treating a 3.8 percent link as an estimate between 2 and 4.5 percent after considering other factors.

Reports from bootcamps and other sources also provide information on job placement and salaries for people changing careers. Good programs will share their placement rates and starting salaries, which are verified to ensure accuracy. Data from 2023-2025 indicate that graduates of high-quality technical bootcamps often report starting salaries in the $60,000 range and a 30-50% increase in pay when switching careers. These numbers can vary a lot depending on the quality of the program and the regional job market. Because schools might try to make their numbers look better, I reduced those numbers by about 30% unless an outside source checked them. This suggests that good bootcamps can provide near-term pay increases that are comparable to those you'd get with a traditional degree.

Studies that follow people over many years show that bachelor's degrees are still associated with higher lifetime earnings, on average. Studies show that people with bachelor's degrees often earn 40-80% more over their careers than those who only finished high school. This is partly because they enter better-paying fields such as finance, law, or research, and partly because they attended selective schools that help them secure top positions. Degrees remain crucial for long-term career growth and for obtaining elite positions. However, for many jobs, employers are increasingly paying for skills that can be proven with shorter, cheaper training.

When studies are observational, I make careful adjustments to account for biases and use verified program data where available. For example, if a study shows a 3.8% correlation, I consider it closer to 2-4.5%. If a bootcamp reports a 50% increase, it's closer to 35% after implementing changes. These lower numbers prevent exaggeration of the results while keeping attention on supporting evidence.

What This Means for Education and Jobs

If the value of a degree is shifting toward proven learning, then our policies need to change to support that. Here's what that looks like: First, degrees need to be broken down into smaller parts. Instead of just a general degree, think of it as a collection of skills that can be assessed and verified. These modules would demonstrate what a graduate can actually do, such as writing computer code, running experiments, or analyzing data. Universities should make their grading system available, showing sample assessments and third-party verification for core skills. This makes it easier for employers to see what someone has learned, rather than relying on the school's name.

Second, funding should be based on results, not just time spent in class. Agencies and public funders can say that schools need to report things like job placement rates, starting salaries, and examples that examinations meet Workplace standards. By connecting funding and accreditation to actual job-market outcomes, we can prevent schools from handing out degrees and force programs that don't lead to skill gains to either improve or close.

Third, encourage excellent teaching within universities. One reason employers don't care as much about classroom teaching is that teaching quality has gone down in some places. This is because schools have been admitting more students and chasing tuition revenue. Bringing back high standards, such as performance-based assessments, rewarding professors for outstanding teaching, and verifying course outcomes by third parties, is vital if degrees are going to maintain a teaching-based premium.

Fourth, Companies need to change how they hire. Instead of just looking at degrees, use performance tasks and portfolios. Hiring trials, work-sample assessments, and accepting checked microcredentials will make hiring easier, expand access, and maintain high standards. Companies that keep demanding selective degrees without evidence that they predict performance should be checked internally and publicly to ensure continued socio-economic standing in hiring.

Some might say that this change will destroy a well-rounded education, reducing degrees to just job training. But that's not true. A college can still have a broad curriculum and verify job skills. By combining in-depth learning with assessments, higher education maintains its value while giving the job market concrete signals it can use.

In conclusion, the value of a degree is increasingly about proving what you've learned. Elite degrees will still matter for top leadership jobs. But for most jobs, employers are paying for skills, not just the school name. Policy should recognize this by demanding checked credentials, redesigning accreditation around verified results, and rewarding universities that combine knowledge with skills. Companies should stop hiding behind degree requirements and start judging candidates on what they can produce. Students should focus on portfolios, not just diplomas. If we use this idea, the education system can do two things: keep the deep learning and civic development that make a well-rounded education worthwhile, and offer clear paths to good jobs for those who need them now.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Chetty, R., Deming, D., & Friedman, J. (2023). Diversifying Society's Leaders? The Determinants and Causal Effects of Admission to Highly Selective Private Colleges. Opportunity Insights.

Credential Engine. (2025). Credential Registry Summary.

Deming, D. (2023). Why Do Wages Grow Faster for Educated Workers? NBER Working Paper.

General Assembly. (2024–25). Program Outcome Reports. General Assembly (audited reports).

Levy Yeyati, E., et al. (2025/2026). The market value of non-degree credentials: New evidence from 37 million US workers. CEPR/VoxEU.

OECD. (2024/2025). Education at a Glance. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Course Report. (2025). Coding Bootcamp Outcomes Report.

Comment