Thickening the Shield: Why Europe Must Accept a Profit Hit for Stronger AT1 Capital

Input

Modified

Europe must thicken AT1 capital buffers even if it permanently lowers bank profits Digital bank runs make thin hybrid capital unreliable in real stress Clear, equity-like AT1 design is cheaper than repeated public rescues

The issue boils down to this: Europe's Additional Tier 1 (AT1) market, which was about $275 billion in early 2023, experienced a major shock when a single large write-down wiped out $16.5 billion in bondholder value almost overnight. These numbers are more than just alarming; they tell a story of who ends up paying when things go wrong, how markets underestimate risk, and why central banks have to step in when banks don't have enough of a buffer. If we're serious about the fact that bank runs are happening faster in the digital age and that the financial system is more interconnected than ever, then we have to face a tough choice: banks need more capital to absorb losses, even if it means their profits take a hit. This isn't a mistake that accounting tricks can fix; it's the main point. Policymakers aren't debating whether to make banks hold more real capital that can absorb losses, but rather how much, what kind, and when they should do it, so that the system remains stable without hurting the banking industry.

Why AT1 capital is important now

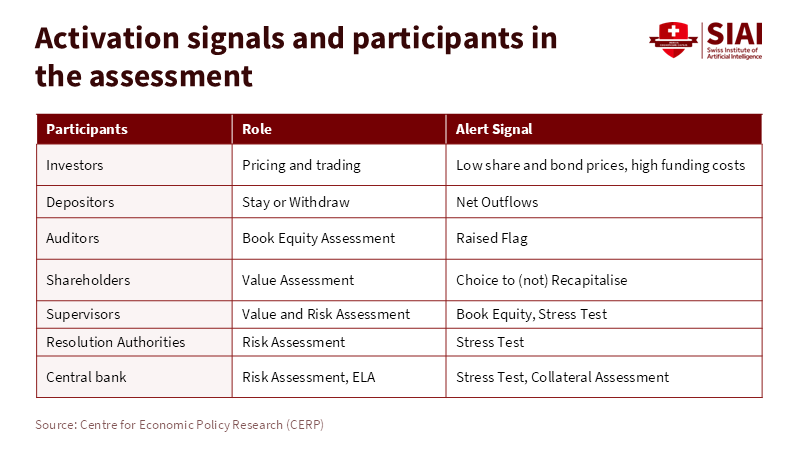

These days, regulators and markets view AT1 capital differently. They see it as a first line of defense that can also act as a shock absorber when things get messy. The events of 2023 – bank runs, rapid deposit withdrawals, and emergency interventions – demonstrated that traditional buffers and central bank loans are insufficient. Central banks can't always be the ones to bail everyone out; that just spreads the losses to the public and creates the wrong incentives. A sound AT1 system, designed to convert to equity or absorb losses while a bank is still operating, shifts some of the burden back to private investors and provides regulators with options other than using taxpayer funds for rescues. That's why the European Central Bank's (ECB) recent ideas to make AT1 more like equity or to rethink its role in the capital structure are relevant to the entire system.

The rise of digital banking makes acting fast more urgent. Deposits can disappear in hours instead of weeks, and information – including panic – spreads instantly. This raises the risk for even well-capitalized banks. In this environment, a small amount of hybrid capital that can't be relied upon during a real crisis is preferable to a solid equity buffer. AT1 is intended to be a compromise: it's cheaper than equity for banks when conditions are calm, but it's designed to share losses with investors rather than taxpayers when trouble arises. The main question is whether AT1 can be improved so it actually works that way, or whether its complexity and legal uncertainties make it unreliable exactly when it's needed most.

Think of AT1 reform as paying for insurance within the bank's financial structure. If the new rules increase the cost of capital, banks will make lower profits. This will squeeze profits, raise borrowing costs, and change how banks do business. But the alternative is the much higher cost of repeated crises for both the government and society. Policymakers need to be clear about this trade-off: being prepared requires sacrifice. The choices they make – like when to convert to equity, who gets paid first, how losses are absorbed, and whether to have consistent legal rules – will determine whether this sacrifice leads to real protection or just more complicated accounting.

How AT1 capital affects bank profits

Banks obtain funds from a mix of sources, including deposits (both insured and uninsured) and market instruments, each with its own interest rate. AT1 instruments usually pay more than senior debt but less than equity dividends. This higher yield is attributable to their being essentially permanent and able to absorb losses. For banks, issuing AT1 can seem appealing because it protects their return on equity by avoiding immediate dilution. However, studies and supervisory monitoring show that banks that use AT1 tend to have lower standard equity tier 1 (CET1) ratios than banks that rely more on equity. AT1 can replace high-quality equity, thereby reducing the system's core capital. AT1 lowers banks' measured capital costs now, but it increases the risk of widespread instability that will eventually impose high economic costs.

The size of the hit to profits depends on how AT1 is designed. If regulators require new AT1s to have stronger equity-conversion features, clearer triggers, and more predictable loss-absorption steps, investors will demand a lower return for assuming the risk. This reduces the gap between AT1 payments and the cost of true equity, thereby limiting the negative impact on bank margins. Conversely, if regulators force banks to immediately replace all AT1 with CET1, banks will need to issue new equity at a higher cost or retain earnings, both of which reduce profits and shareholder returns. Either way, bank profits will be squeezed; it's just a matter of how quickly and by how much. Issuance data indicate that markets are adapting: after 2023, issuance slowed but has since recovered, suggesting that investors will adjust their pricing rather than withdraw if the legal situation is clarified.

It's tough to accept that profits will fall. Bank executives will correctly point to competition from other countries where capital rules are less strict. That's a valid point. But a system where some banks can hide behind hybrids while others bear higher equity costs encourages rule-breaking and concentration. The goal should be to set consistent standards that make any profit hit predictable. If markets and managers can anticipate the rules, they will adjust their business models gradually rather than being forced into disruptive recapitalizations during a crisis. The reward is a banking sector that is less volatile and less likely to require government bailouts, even if it means lower profits.

Capital arbitrage and weak buffers

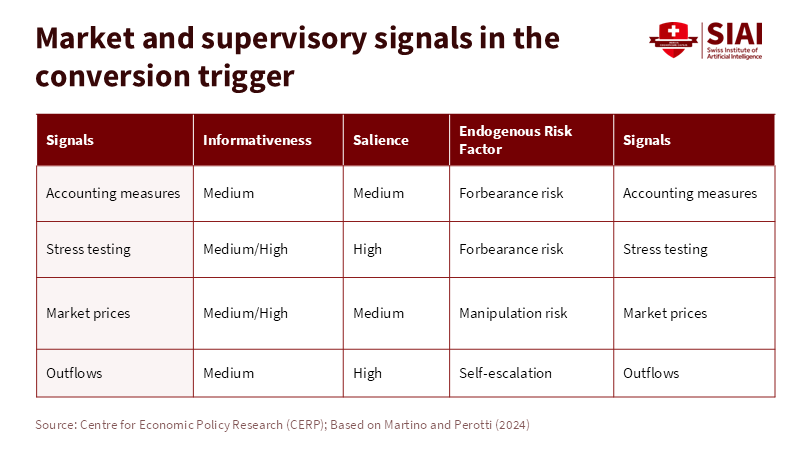

gaming the system – the ways banks can meet regulatory requirements while still having fragile capital structures – remains a problem. Monitoring shows significant differences among banks in their AT1-to-CET1 mix and in how these instruments behave under stress. Where AT1 issuance has been high, CET1 tends to be lower, suggesting that banks are using hybrids as substitutes rather than additions to their capital. Even worse, legal and supervisory uncertainty following major write-downs may lead investors to distrust AT1's ability to absorb losses while a bank remains operating. This undermines the instrument's very purpose and creates a false sense of security. The European Banking Authority's (EBA) monitoring raises questions about the links among conversion triggers, the use of loss-absorbing mechanisms, and fragile legal designs that enable adverse outcomes.

The Credit Suisse situation is a clear example of how legal design and political factors can make hybrids appear protective when they aren't. Authorities dismissed AT1 in a high-profile emergency, and the subsequent lawsuits have raised doubts about when and how AT1 should be used. These legal issues are important: if regulators cannot demonstrate that AT1 will reliably absorb losses before government support is required, private capital will not perform as intended. Investors want clear contract terms and predictable supervisory practices. Without these, banks may appear to meet capital requirements on paper while still being fragile. Recent Swiss and cross-border litigation highlight the reputational and legal risks associated with regulatory ambiguity.

Cheating also takes other forms: optional coupon deferrals, temporary capital relief, and complicated securitizations that shift risk to less-regulated parts of the market. Any serious reform needs to close these loopholes. This means removing ambiguous clauses, setting minimum CET1 levels that cannot be replaced by hybrids, and standardizing triggers and conversion mechanics across different countries. Supervisors also need the legal authority and technical capability to enforce these rules when challenges arise. Without that, thick buffers are just theoretical. The credibility of the entire system depends on binding, predictably enforced rules.

Practical rules for AT1 capital

First, set a non-negotiable CET1 target to ensure hybrids are truly supplementary. Second, redesign future AT1 issuances to include mandatory equity conversion mechanics with a simple trigger and clear steps, preventing situations in which AT1 is written down while equity survives. Third, implement these changes gradually so banks can rebuild capital without sudden shocks to their profitability. These design choices accept that profits will take a hit, but they manage the pace and distribution of that hit. The ECB’s recent willingness to make AT1 more like equity or rethink its role in the capital stack aligns with this approach.

How much is enough? There’s no one-size-fits-all answer, but transparent estimates can guide policy. According to the European Central Bank, a practical approach could be to enhance banks' loss-absorbing capacity by revising the role and design of Additional Tier 1 (AT1) and Tier 2 instruments, ensuring that capital structures are better able to absorb severe shocks while changes are phased in over time. The goal is a capital profile that would significantly reduce the need for extraordinary government support in future crises. Evidence from supervisory stress tests and past failures indicates that thicker buffers significantly reduce the likelihood of resolution, even if they lower returns.

How it's implemented matters. Standardized contract terms for AT1, cross-border legal clarity, and a supervisor-approved conversion plan will reduce investor uncertainty and narrow spreads. According to the European Council, the Basel III reforms introduce an "output floor" to ensure that banks maintain adequate and comparable capital requirements, thereby reducing the risk of excessive lowering of these requirements and strengthening resilience against economic shocks. The alternative – ambiguous rules and ad-hoc rescues – simply shifts volatility from private contracts to public budgets.

The opening figure should serve as a warning now, as it carries a price tag. According to the European Banking Authority, the 2025 EU-wide stress test covered a significant portion of the sector and highlighted the need for banks to focus on resilience through adequate loss-absorbing capital, even if it means accepting lower returns rather than relying on financial instruments that might not function as intended during crises. This means a CET1 level, AT1 redesigned to convert with clear rules, and a phased timetable that allows banks to adapt. The alternative – relying on central-bank absorption and crisis-by-crisis fixes – will be far more costly. Policymakers must make the harder choice now: reshape incentives so private capital carries more risk during stress, and let government backstops play a true last-resort role. The profit squeeze is real. It is also the price of keeping the system intact for the next generation of shocks.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

BIS — Bank for International Settlements. Report on the 2023 banking turmoil. Basel: BIS, 2024.

EBA — European Banking Authority. Report on the monitoring of Additional Tier 1 (AT1), Tier 2 and MREL instruments. Paris: EBA, June 27, 2024.

ECB — European Central Bank. Governing Council proposes simplification of EU banking rules. Press release, Dec 11, 2025.

FT — Financial Times. “ECB considers ditching AT1s to 'increase quality' of banks' capital.” Dec 2025.

Kothari, Vinod. “AT1 Bonds: Death before it is due?” March 25, 2023. (Market estimate of AT1 outstanding).

RBC Capital Markets. “Can Europe's bank equities and AT1s comeback be sustained?” April 7, 2025 (issuance and market commentary).

Reuters. “Swiss regulator appeals court decision on Credit Suisse bonds write-off.” Oct 2025.

UNRELATED MARKET & INDUSTRY DATA (selected): AFME. Prudential Data Report — Q1 2025 (AT1 issuance data).

Comment