When Coins Become Code: Why Payment Rails and Monetary Sovereignty — Not Tokens — Decide Who Holds Power

Input

Modified

Payment rails, not digital tokens, now define real monetary sovereignty Stablecoins change the form of money, but control depends on who governs settlement and redemption Policy power survives only if tokenized money clears on domestically regulated infrastructure

In June 2025, the total value of dollar-pegged stablecoins hit roughly $252 billion. This isn't just a small crypto detail; it's a widely used and easily transferable way to pay. Stablecoins now fit somewhere between regular bank accounts, card networks, and central banks. If these tokens are truly backed by assets held locally, their growth shouldn't automatically threaten national currencies. The big thing is where the clearing, settlement, and rules are set. The question isn't whether money can be tokenized—it already is. Instead, we should be asking whether tokenized money is moving through systems controlled by our own institutions or through global networks run by foreign companies. Basically, the format might change, but control decides who's in charge.

Why payment systems and monetary control should lead the discussion

A common mistake when discussing policy is focusing on the financial tools rather than the systems that power them. Many people see stablecoins and central bank digital currencies (CBDCs) as rivals, but they are both just digital claims. The real competition is in how payments are processed. If a fully backed stablecoin is used in a country on settlement systems controlled locally, it works a lot like a regular bank deposit but in a different form. But if that same token is used across borders on digital wallets and ledgers run by companies from other countries, our own policy tools—like reserve requirements, emergency lending, capital controls, and anti-money-laundering rules—become less useful. That's how a simple tech change turns into a question of who's in charge. The proof is clear: stablecoins have grown rapidly, but the real risk arises when their clearing moves beyond our national control.

This view moves the attention from the tokens themselves to how they're managed. Central banks are right to worry about 'outside money' taking over national currencies in everyday use. But, governments can stay in control by making sure tokenized money, no matter what it's called, is settled on systems that follow the rules and support our policy goals. One way to do this is with a retail CBDC. Another is to make stablecoin creators and major custodians clear transactions through local settlement accounts or under our own laws. The main policy question is how to connect tokenized claims to our control points, not whether digital tokens should exist. This is important now because the amount of tokenized liabilities is big enough that retail use can affect lending, government income, and money moving in and out of the country.

Stablecoins as a form, not a takeover: what the numbers tell us

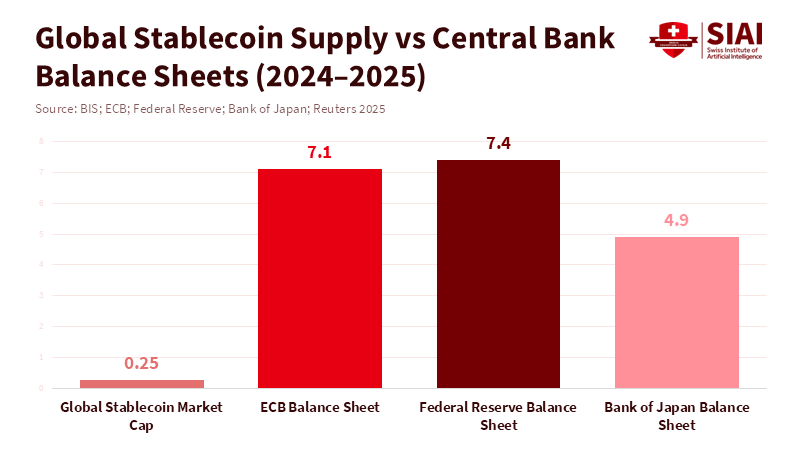

Stablecoins are important now, but they don't have unlimited power. By mid-2025, the total value of dollar-pegged stablecoins was in the hundreds of billions of dollars. The two biggest creators each have tens of billions in outstanding claims. For instance, Circle said that USDC reserves were over $40 billion at the end of 2024, mostly in short-term U.S. Treasury and other easily sold assets. These are big numbers, important for crypto markets and some payment methods, but still small compared to total bank deposits or central bank balance sheets in major economies. The key isn't just the size, but how and where these tokens are being used. A $40 billion token supply, if it's all focused on one cross-border payment network, can affect how easily smaller countries can access cash. If it's mainly used within regulated systems here at home, it mostly replaces existing claims without putting our control at risk.

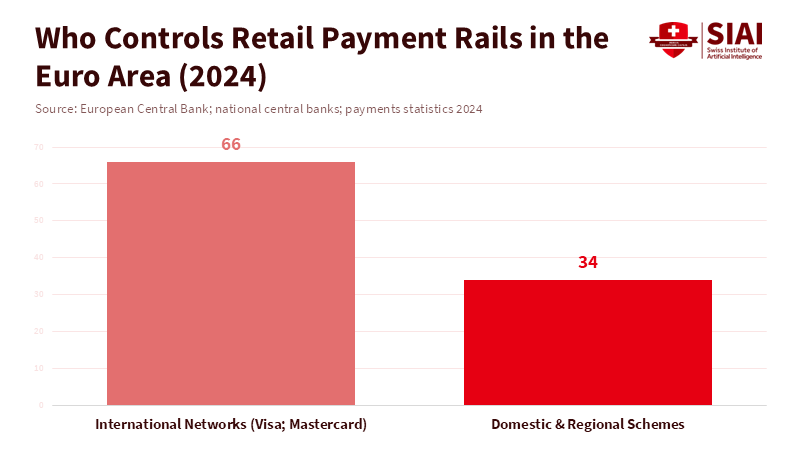

We can gauge how exposed we are to external systems by looking at two things we can see: how many stablecoins are out there and how many consumer payments are handled on card and network platforms outside the country. In the euro area, for example, about two-thirds of card payments were handled through international networks in the first half of 2024—a reliance that was there even before tokenization. If stablecoins go through those same non-resident operators or digital wallets run by foreign firms, then tokenization makes that reliance even bigger. The math is simple. When a country already sends a lot of its retail transactions through international processors, the effect of tokenized tools isn't on the ledger; it's about who decides disputes, who gets access to the data, and who makes the rules. If our regulators can't force those processors to provide real-time transaction data or stop illegal flows, the token becomes a means for outside forces to exert influence.

How to protect control when coins are just code: three policy actions

First, regulate the payment systems. Control depends on having legal power over clearing and settlement locations. This means issuing licenses and monitoring not just the creators, but also the custodians, wallet providers, and node operators who handle final settlement. Regulators should demand that stablecoins used by the public in a country can be exchanged at face value for central bank money through partners watched locally, and that settlement is completed within a system regulated here. This doesn't ban cross-border token flows for big financial deals; it just points retail money to places where our policy tools can be used. The result is that tokens become a neutral form of money, not an unregulated option. For teachers and administrators, this means that courses and risk policies should treat token-based payments as part of the regular payment system, like cards or automated clearinghouses, not as something weird.

Second, update access to the central bank and good settlement assets. If only local banks hold the power to redeem, sudden moves into foreign tokens can still cause problems. A strong approach makes central bank balances or overnight treasury claims widely available to licensed token custodians, subject to strict liquidity and reporting conditions. This makes it faster for regulators to fix things in bad situations. It also gives a practical way to connect things: stablecoin issuers can hold required backing in instruments linked to the central bank, shortening the path from token to real money. For administrators, this means new custody rules and audits. For teachers, it changes what core finance is: custody and settlement design become public policy, not just back-office choices.

Third, demand clear info and regular reserve reports. One concern with stablecoins has been a lack of clarity, but this has improved lately with more frequent statements and clearer rules in some countries. Making regular, standard reports on what reserves are made of, who's holding them, and how redemptions work makes it less likely that a token will act like a secret foreign currency. If disclosures are missing or custodians aren't clear, regulators should limit how these tokens are used in retail payments or ask for more local backing. This approach helps innovation while protecting monetary policy. It also gives academics and central banks the info they need to teach, model, and plan for tokenized money situations.

Getting ready for and answering common criticisms

A common complaint is that regulation kills innovation, and that any connection to our own systems will slow token payments and increase costs. This misunderstands two things. First, innovation in payments is as much about how it feels to the user as it is about what's happening behind the scenes. Well-designed local rails can offer fast settlement and low fees while still allowing regulatory oversight; offline and hybrid CBDC designs make this possible. Second, private stablecoin projects have strong business reasons to comply with the rules in major markets. Clear rules sell. When issuers know the rules and what it costs to break them, they'll change their products to fit. The bigger danger is a confusing approach that pushes merchants and users to unregulated paths. Evidence from 2024–25 shows that regulation that focuses on enforcement and visibility into what's happening has been linked to faster adoption by institutions and lower risk to the system.

Another worry is that this is an all-or-nothing choice: either accept global tokens and give up control, or resist and fall behind. This isn't true. Control is protected not by blocking new forms of money, but by ensuring tokenized money operates within institutions that can deploy policy tools. Countries that offer fast, affordable, and regulated token payment systems will attract business because they combine convenience with legal safety. The real policy challenge is to design institutions that enable our systems to work with global ones while maintaining oversight. Training for central banks and teaching programs should focus on standards for working together, legal rules for sharing data across borders, and making systems strong—not just on the tech itself. The goal isn't to stop innovation, but to guide it.

Back to the first idea and a call to action

Tokenization is here to stay. Stablecoins and CBDCs will continue to grow because they meet real needs for speed, ease of cross-border transfers, and programmability. But control over money doesn't depend on the token itself, but on who runs the clearinghouse, manages the ledger, and has the legal power to enforce rules and disclosures. If euro- or dollar-linked tokens are used in stores in Athens and can only be exchanged through foreign custodians outside Greek or EU control, then local monetary policy loses its power. But if those tokens must settle through accounts governed by our laws and can be exchanged at face value for central bank money, they remain our own currency, not a competitor.

Policymakers should move from theory to three clear steps. First, establish licensing rules for all parties involved in the retail payment process: issuers, custodians, wallet providers, and node operators. Second, allow licensed custodians to access central bank settlement, subject to strict requirements. Third, demand regular, standard reserve disclosures and legal promises that stablecoins used by the public can be redeemed. Teachers, regulators, and technologists should build training and guidelines that treat token design as part of payment systems and the law. Money will be digital, but control will depend on strong institutions. We can have both, if we make sure the payment systems keep control where it belongs.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank for International Settlements. (2025). Results of the 2024 BIS survey on central bank digital currencies and crypto (BIS Papers No. 159). BIS.

Circle. (2024). USDC reserve attestation report, December 2024. Circle / Independent Auditor Report.

European Central Bank. (2025). Payments statistics: first half of 2024. ECB Statistical Releases.

European Central Bank. (2024). Progress on the preparation phase of a digital euro (May–October 2024). ECB Reports.

International Monetary Fund. (2025). Cerutti, E., Understanding Stablecoins. IMF Research and Discussion Paper.

Reuters. (2025, June 18). Stablecoins' market cap surges to record high as US senate passes bill. Reuters News.

Banque de France. (2025). Central bank digital currency: the sovereignty challenge. Speech / Governor interventions.

Comment