The Cost of Hurry: Why the speed of AI adoption is a policy choice with winners, losers—and no shortcuts

Published

Modified

AI speed is a policy choice, not a universal race Rushing adoption can deepen inequality and strain education systems Measured AI adoption builds lasting capacity and stability

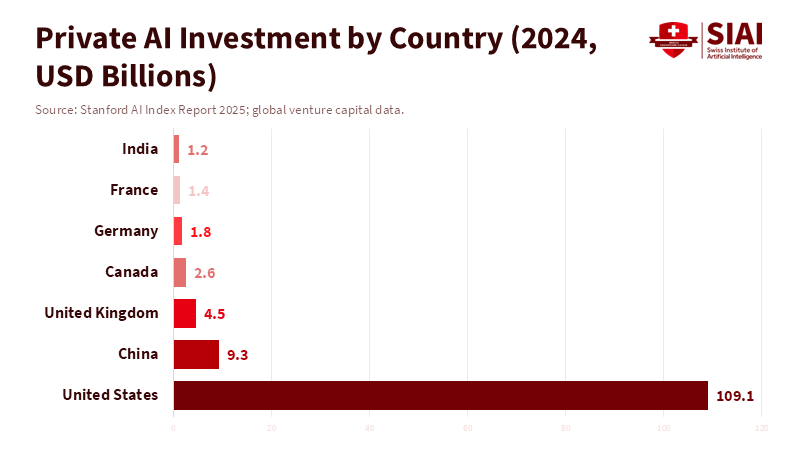

In 2024, the United States saw a substantial amount of private capital flow into AI, far surpassing that of any other country. Approximately $109.1 billion in new private funding was invested, about 12 times the $9.3 billion China invested that year. This has led to a concentration of talent, computing power, and market power in a small group of leading companies. This unevenness is significant because being a leader in tech isn't usually about just one brilliant idea. It depends on having a robust system that includes money, substantial power, talented people, and the ability to try things that might be expensive failures. When you have a lot of resources in one place, you can move fast. But if you don't have those resources, trying to move fast can be a disaster. So, every education official, college leader, and job market planner needs to think not about whether AI will change things, but how quickly we can adapt our systems to handle those changes. Trying to go fast without having the right resources means sacrificing important things in the future to look good today. It leaves teachers, experienced workers, and entire economies struggling to keep up with a disadvantage.

Why it's important to think about how fast we adopt AI

People often talk about adopting AI like it's an all-or-nothing situation: either you jump in, or you get left behind. But that's not the whole story. How fast you adopt AI can actually make existing advantages even bigger. If you already have a lot of money, strong research centers, and plenty of cloud computing, you can not only use AI models, but also mold the standards, data processes, and even the kind of talent that's considered normal. This creates a situation where the first movers set the rules. What's taught in schools, the qualifications people need, and even job descriptions start to reflect the tools and methods used by those leading companies, instead of what most schools or firms can actually manage. For schools that need to serve everyone, the pressure is on to copy those tools in the classroom. This can mean buying cloud services, installing expensive equipment, and hiring a few specialists. Meanwhile, the majority of teachers don't get the support they need. This turns updating education into a fancy project for a select few, instead of a real improvement for everyone.

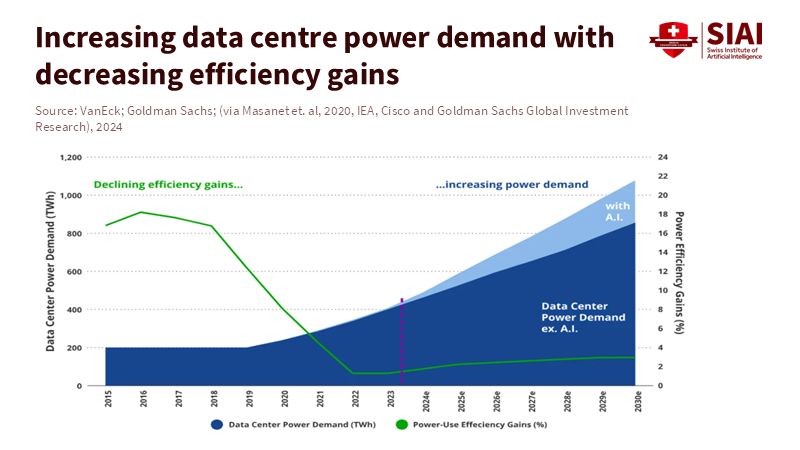

There's another reason why speed is important: money. To go all-in on AI, countries need to invest in data centers, skilled trainers, software licenses, and a reliable power supply. If governments or universities focus on short-term benefits instead of building a solid base, they could end up with financial problems later on. Public budgets are already tight, and adopting AI quickly can increase costs, which can be hard to see at first. At the same time, the benefits, like better productivity, new courses, and improved learning, usually take time to show up. If a government borrows money to build a fancy AI center but can't find the people to run it or the power to keep it going, that center becomes a waste of money. This is already happening in places where private AI investment is high, but public finances are stretched. Going fast isn't the same as being able to include everyone in a way that's affordable.

A world of different speeds for AI adoption

The world is dividing into three groups regarding AI. The first is the superpowers that are racing ahead. In this case, companies and countries are competing intensely to be the leader in AI platforms. They're willing to spend a lot of money to win, even if it's risky. For them, moving fast makes their lead even bigger. Their education systems will likely prioritize state-of-the-art research and retraining programs for a select few. This could increase inequality within those countries, but they can handle the risks and costs of leading the way in AI. They see their investments as part of a larger plan, not just one-time experiments.

The second group is small and middle-income countries. For them, trying to keep up with the leaders can be a huge struggle. They face three problems: they lack sufficient private capital or cloud and chip infrastructure to reduce costs. They also have gaps in skills, especially among older workers. This means that rapid adoption of machines and AI can displace older workers, and they may find it difficult to transition to a new career. According to research by Neumark, Burn, and Button, there is strong evidence that older women, particularly those approaching retirement age, face age discrimination when trying to find jobs. Additionally, these countries frequently have limited budgets, so allocating funds for AI infrastructure can reduce the money available for social and educational programs. This creates a difficult situation: they must choose between allocating funds to emulate AI leaders and investing in foundational systems. The infrastructure reality makes the pace question unavoidable. Data centre electricity demand is accelerating sharply, even as efficiency gains flatten compared to earlier years. Rapid AI scaling now requires sustained capital, reliable grids, and long-term energy planning — resources not evenly distributed across countries.

The third group is a large middle zone, which is everyone else. These countries aren't racing ahead, but they're also not maintaining their basic capabilities. Without a clear plan, they risk slowly falling behind. Public research doesn't receive sufficient funding, companies lack access to high-quality AI models, and the job market loses middle-skill jobs without providing adequate options for people to find new work. These countries become dependent on AI services provided by others and lose control over standards and data use. The message for them is clear: going fast without having the resources to do it right isn't a way to become competitive.

These three groups aren't about judging which is better or worse. It's about understanding the financial and organizational realities they face. Moving fast makes sense if you control the infrastructure and can afford to take losses. But for everyone else, the right question isn't How fast can we adopt AI? but How can we learn at a pace that allows us to adapt? Going slow doesn't mean doing nothing. It means taking steps in the right order: first, invest in helping teachers understand technology, then redesign courses to focus on solving problems, and finally provide reliable power and internet access. Then, you can start using AI platforms. This approach reduces the risk of wasting money and makes it possible to speed things up later in a way that makes sense.

What the speed of AI adoption means for educators, administrators, and policymakers

Educators need to determine what's most important to teach about AI. A good rule is to focus on skills that will last. Critical thinking, judgment, supervising AI models, and understanding data are skills that will be useful regardless of the tools available. Courses that teach people how to work with AI, like how to write instructions for AI, how to evaluate what AI produces, and how to oversee decisions made with AI, are helpful. But they shouldn't replace a solid foundation in other subjects. Buying many specific classroom tools can trap schools into using them, and it can be hard for teachers to adopt them. Instead, schools should focus on training teachers and creating course materials that gradually include AI tools, with ways to measure how well they're working.

Administrators and finance teams need to consider how quickly they plan to adopt AI when setting budgets. When universities or school systems are planning to buy AI tools, they should carefully consider the costs of running them. This includes energy use, license renewals, technical staff, and equipment replacement. Rapidly adopting AI often shifts costs from one-time investments to ongoing expenses, which can be difficult to cut later. A better approach for systems with limited money is to take things slowly. Start with small experiments, measure how well they're working and how they affect the job market, train people, and then expand. International cooperation should focus on building capabilities rather than just donating equipment. Donating equipment without training and a budget to keep it running creates dependence, not self-reliance.

Policymakers need to think about how people will transition to new jobs, especially older workers. Studies show that older workers face challenges finding new jobs as automation and AI replace their roles. Just retraining older workers quickly often doesn't work because of difficulties related to learning, location, and finances. Better approaches include offering options for gradual retirement, retraining people for local jobs, and offering credentials that recognize their prior experience. Social insurance and wage subsidies can provide support as people adjust, and programs that help them find new jobs can increase their chances of employment. These measures cost money, but they're cheaper than the cost of mass unemployment and social problems caused by adopting AI too quickly.

A practical plan: taking things in the right order, being honest about costs, and adopting AI at a measured pace

A plan that treats speed as a tool, not a race, has three main parts. First, take things in the right order. Focus on providing reliable power, universal internet access, teacher training, and open standards. These are the things that make adopting AI later on more effective and affordable. Second, be honest about the costs. Consider the total cost of owning AI tools, not just the initial investment. Include energy, staff, and replacement cycles. If a government borrows money to build fancy AI centers without a realistic plan for running them, it creates problems for the future. Third, regulate access wisely. Make sure that purchasing favors systems that can work with other systems, encourage shared computing facilities, and require educational licenses that allow for research, reuse, and evaluation. These steps lower the initial cost and increase the chances for learning.

International partners and organizations can help by shifting their focus from donating equipment to building lasting capabilities. Grants or loans should fund teacher training, regional computing centers, and curriculum development, rather than just individual AI centers at universities. When offering financial support, set measurable goals, such as teacher certification rates, improvements in learning outcomes, and job placement rates, so that success can be measured. This is how to turn good intentions into real benefits for the public.

Finally, the speed of AI adoption must be a democratic decision. Decisions about how quickly to adopt AI are political choices that affect different groups and regions. Open discussions among teachers' unions, universities, industry, and the public can reduce the risk that AI adoption becomes a project for a select few. When educators and communities are involved, the pace is more likely to protect jobs while allowing innovation to continue.

Remember that substantial private investment has already created a situation in which only a few can afford to move quickly with AI. For everyone else, trying to keep up is a risky bet. The alternative isn't to reject AI, but to choose a responsible pace, proceed in the right order, budget honestly for operating costs, and protect workers. Educators, administrators, and policymakers should focus on supporting teachers and on teaching skills that endure. Getting the pace wrong will not only delay the benefits of AI but will also worsen inequality, create stranded assets, and weaken the ability to manage technology. Getting it right means using a measured pace as a plan for inclusion, making decisions based on evidence, and focusing on the good of the public.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

BBC News (2024) US power grid faces strain from AI-driven electricity demand. BBC News.

Brookings Institution (2024) Why Africa should sequence, not rush into AI. Brookings Institution.

International Monetary Fund (IMF) (2025) Global Debt Monitor 2025. International Monetary Fund.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2024) Promoting Better Career Choices for Longer Working Lives. OECD Publishing.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2025) Emerging divides in the transition to artificial intelligence. OECD Publishing.

Reddit (2025) The AI is so fucked you can’t play small nations. EU5 Discussion Forum.

Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI (HAI) (2025) AI Index Report 2025. Stanford University.

VanEck (2024) Who’s winning the AI rush?. VanEck Vectors Insights.

Comment