Narrowing the Flame: AI resource allocation and the practical prevention of wildfires

Input

Modified

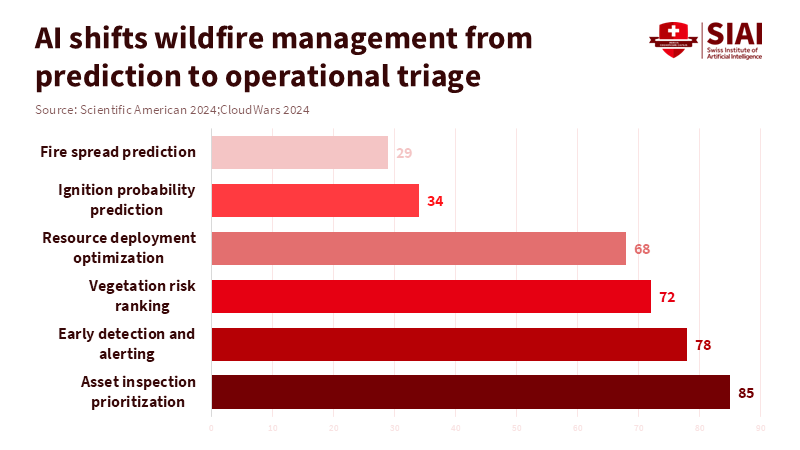

AI is changing wildfire management by prioritizing where human effort matters most, not by predicting fires. Human-in-the-loop systems cut response time and reduce ignition risk under tight resource limits. This shift turns wildfire control from emergency reaction into practical prevention.

Wildfires don't wait around for the perfect prediction. In 2023, about 2.7 million acres burned across the United States. But that number doesn't tell the whole story. The worst damage usually occurs in areas where old infrastructure, dense brush, trees, and people converge. The big challenge for policymakers isn't just getting perfect forecasts. It's deciding how to use resources well. Systems powered by computer intelligence can help with this. They can rank things like utility poles, land areas, patrol routes, and inspections based on how much good each one will do. This helps get the most out of the limited number of people and money available for maintenance. Even a small change in how things are done can prevent big losses. This isn't about replacing people with machines. It's about creating things that direct technicians to the inspections, power shut-offs, or brush clearing that will probably reduce the chance of a fire starting. People in charge still make the final decisions, while the computer intelligence provides them with a list of priorities.

Computer Intelligence: Changing How We Think About Wildfire Handling

Using computer intelligence to allocate resources changes the main question in wildfire policy. Wildfires occur due to weather, dry conditions, faulty infrastructure, and human activity. Predicting exactly where a fire will start, far in advance, is always going to be difficult. Instead of asking, "Where will the next fire start?" agencies should ask, "What action can we take today to reduce the risk of a fire?" This small change in wording changes how models are designed and tested. Models don't need to be perfectly accurate about location anymore. They just need to reliably rank assets so crews get a short, useful list each day. The information that goes into the models can be simpler and easier to manage, such as lists of assets, LiDAR-derived measurements of tree cover, recent problem reports, and real-time alerts from cameras or sensors. The results should be risk scores that show the order of importance, clear reasons for the scores, and ranges of certainty, instead of just simple yes/no predictions.

It's really important to be organized in our methods. According to a study by Noonan-Wright and Seielstad, land managers best evaluate prioritization strategies by trying them out in areas with similar conditions. If random testing is not possible, managers can still collect valuable information based on the results of different approaches. Do this by comparing areas with and without the new methods, and by making sure to look for any trends that existed before the new methods were put in place. Important metrics include the number of top-priority assets inspected per period, the time to alert after a fire is detected, and the frequency with which alerts from the computer intelligence system trigger actual actions. These metrics directly connect what the model says to what people do and how safe the public is. They also show if there are any inequalities, like if the system isn't working well in rural or low-income areas. If that happens, sampling and checking plans are needed to fix those problems.

Computer Intelligence in Action: Examples and Proof

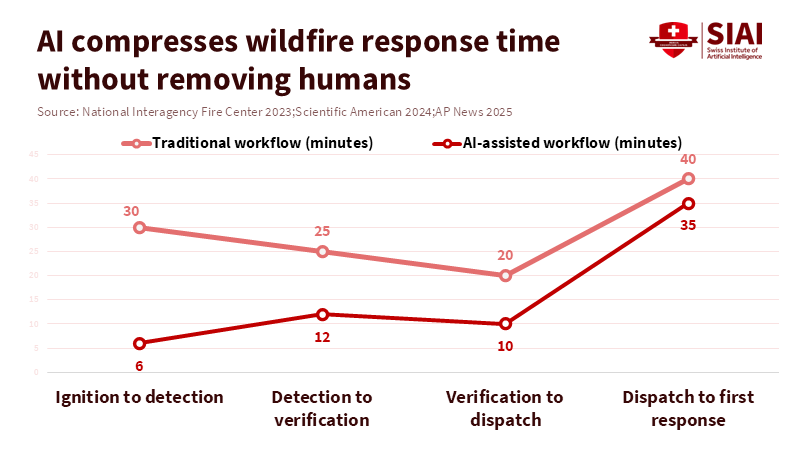

Real-world examples show that this way of thinking works. Utilities and land managers who use cameras on towers or poles, combined with machine learning, have reported that they get alerts faster. As a result, they can do maintenance in focused ways. In some test locations, alerts from cameras reduced the time to detect a fire from many minutes to less than five minutes. This lets verification teams and dispatchers confirm and act while the fire is still small. At the same time, platforms that analyze vegetation combine tree-cover data from LiDAR, satellite measurements of vegetation, and asset lists to generate inspection lists that identify the highest-priority items for crews to address immediately. Faster alerts and focused inspection lists are changes that are important for stopping wildfires.

Looking at national numbers can be misleading. The number of acres burned in the U.S. changes a lot from year to year. For instance, about 2.7 million acres burned in 2023, and 2024 saw different patterns in different regions. So national totals aren't that helpful for judging how well a local action is working. Instead, it’s more helpful to do calculations at the local level. According to a report from the United States Joint Economic Committee, wildfires cost the nation between $394 billion and $893 billion each year. This shows how valuable it is to take actions that lower the risk. Imagine that focused inspections and quick, verified alerts could lower the chance that a fire in a high-risk area becomes a big wildfire by 10 to 20 percent. Applying that reduction to local models of exposure and fire suppression costs would lead to real financial savings and lower emergency costs. Even if you make conservative assumptions, it almost always makes better financial sense to assign limited crew hours to the top-priority assets than to do inspections randomly.

New technologies can make this even better. Semi-autonomous drones guided by computer intelligence can be sent to identified hotspots. They can provide infrared and regular pictures within minutes. Networks of sensors can detect gases or unusual heat from smoldering materials before flames even appear. According to the FireCon decision support system, verification tools are designed to help workers handling wildfires quickly identify the areas most easily contained and to guide interventions such as pruning and pole replacement. Together, cameras, sensors, and drones reduce the time it takes to detect and verify fires and let crews do more high-value inspections.

Computer Intelligence: Improving Human-Centered Systems

The key is systems where people and technology work together, where the computer model ranks and explains, then technicians check and act, then the results of those actions become training data for the model. Explainability isn't just for show. Crews won't change their work for a score that doesn't make sense. They'll act when they see clear reasons for flagging an asset, such as tree branches overhanging, proximity to a transformer, repeated fault calls, or anomalous sensor readings. Easy-to-use interfaces that quickly show these factors allow a supervisor to act fast and make corrective adjustments. Those corrections improve the models in the areas where it matters most: the small number of assets that carry the most risk.

This setup also supports good governance and accountability. When people approve of actions. If these actions have consequences, such as shutting off power or conducting selective shutdowns, legal responsibility is apparent and can be verified. According to the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, keeping records of who made decisions, what actions were taken, and when they were taken allows regulators and the public to review and understand why certain actions were taken. This helps build public trust and provides a clear record for accountability. The model where humans are in the loop is also challenging, as it addresses model errors by ensuring that trained people can use local knowledge to make decisions.

To make this more widespread, some things will need to change in how purchases are made, how people are trained, and how compliance is managed. According to a report from the U.S. Department of the Interior, addressing wildfire challenges requires a proactive, comprehensive approach that emphasizes sustainable solutions and strengthens community and landscape resilience to wildfire. The target top-ranked assets. Training programs need to qualify technicians. The technicians need to interpret model outputs, give feedback, and understand risks. Ultimately, budgets must support the personnel needed for wildfire response. Using analytics alone makes dashboards. Combining analytics with people in the field results in fewer fires action.

A List for Computer Intelligence: Wildfire Policy

Specific policy actions are needed to make this idea a reality. First, make human-in-the-loop standards required in purchasing processes. When choosing vendors, evaluate them based on explainability, API compatibility, and demonstrated improvements. Second, require pilot programs that have pre-registered plans; plans such as randomized rollouts or matched controls: also use pre-analysis plans to be prepared to be able to verify claims and results. Third, require public reporting of key operational metrics, including the percentage of top-priority assets covered, the median detection-to-alert times, and the mean time. The mean time needs to be from alert to verification, and the percentage of high-cost actions needs to be directed at top-ranked assets. Although these actions may seem minor, their impact is meaningful, realigning the organization toward measured actions.

Fourth, combine financial structures and incentives. Implement performance-based contracts that link a portion of vendor payments to verified reductions in inspection backlogs or shorter alert windows. Reassign some of the suppression-only budgets to wildfire action when analytics show improved targeting. Fifth, protect fairness and individual rights by requiring audits of data. Identify underserved areas that require equity-weighted prioritization, if necessary, and ensure that the deployment and use of cameras and sensors adhere to privacy and civil liberties standards. Sixth, require human approval and detailed records of actions to ensure liability is auditable and well distributed. These steps create an equitable and sound system.

Implementation Plan: In order to create and to make pilots scalable, a three-stage program can be used. Stage one (0–12 months) should fund 6–12 geographically dispersed, high-risk pilots to take action. A report from Arkowitz and colleagues recommends that each pilot project in wildfire management should be guided by a comprehensive plan, use matched controls or randomization when feasible, and commit to sharing sanitized operational data and action metrics. The report also suggests these pilots should focus on crews acting quickly to validate issues and provide strong outcome labels. According to RMI, while the bill does not require utilities to take specific steps, it establishes a framework for statewide collaboration on wildfire risk management. The work group is meeting actively and is expected to deliver its recommendations to the legislature and key agencies within a defined timeline, with clear inspections.

Funding and standards are extremely important in addition. National governments and regional authorities can use open tech standards, priority listing, and contracts. Open tech standards can produce integration for public agencies. The authoritative source does not provide information to verify or support this claim. Templates can be shared and learning, action can be created during global operations.

If we move forward in a transparent action, focus on protection, and human discernment, then the outcomes will be to protect. This isn't just a tech-driven leap. It is a pragmatic solution, action, and measurable program. Through these pilots, people can collect data, assess rights, and scale proven resources and strategies. If strategies are followed, prevention will be created, and ignition will decline. Act now.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP News (2025) An AI-based drone that speeds up the detection and monitoring of wildfires is presented in Germany. Associated Press.

Boroujeni, S. P. H., et al. (2024) A comprehensive survey of research towards AI-enabled wildfire management. Environmental Modelling & Software.

CloudWars (2024) From resource allocation to demand forecasts: AI drives unexpected ecosystem savings. CloudWars, Innovation & Leadership.

MDPI (2025) AI-enabled wildfire management: From prediction to detection and response. Fire, MDPI.

National Interagency Coordination Center (2023) Wildland fire summary and statistics annual report 2023. National Interagency Fire Center.

National Interagency Fire Center (2024) Total wildland fires and acres burned in the United States. National Interagency Fire Center.

NOAA National Centers for Environmental Information (2023) U.S. wildfire activity and climate conditions: Annual report. NOAA.

Scientific American (2021) AI could spot wildfires faster than humans. Scientific American.

Scientific American (2024) How new AI technology is helping detect and prevent wildfires. Scientific American.

Xu, H., et al. (2025) Generative AI as a pillar for two- and three-dimensional wildfire spread analysis. Fire, MDPI.

Comment