AI Tax: When Memory Becomes an Education Levy

Published

Modified

The AI Tax is turning memory scarcity into a hidden cost on education Rising DRAM prices push computing access out of reach for many schools and families Without action, personal computers risk becoming a privilege again

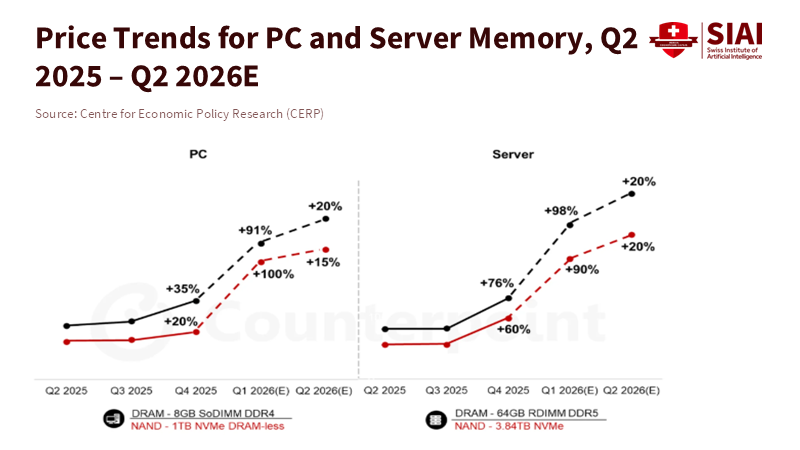

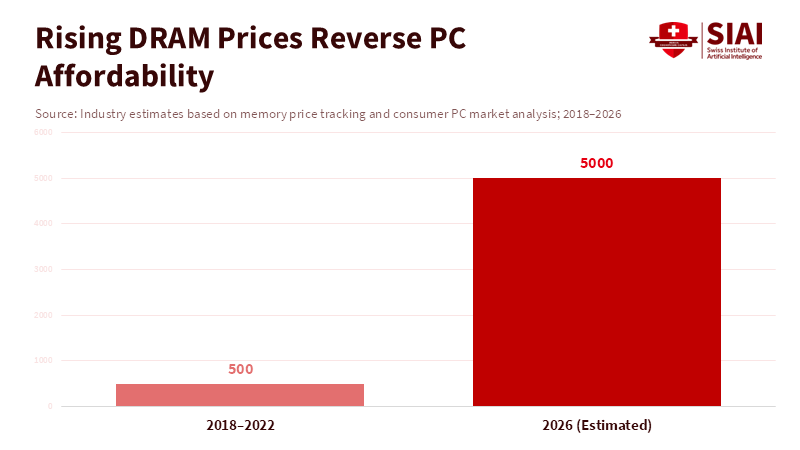

The price of memory is the new tax on learning. In late 2025, global memory prices jumped roughly 50% in a single quarter and analysts now warn of another doubling as data centers gobble AI-grade DRAM and HBM. This is not a distant supplier glitch. It is a structural pivot: wafer capacity, packaging lines and advanced-process allocation have been steered toward servers built to train and serve large models. The result is an AI Tax—an implicit added cost that falls on every device, classroom, and campus that relies on current computing. That tax is already reshaping procurement plans, delaying upgrades, and forcing schools to choose between connectivity, compute and curriculum. The urgent question for teachers and decision-makers is simple: how do we prevent a technological rollback—where modern personal computing becomes a luxury again—while the AI sector consumes the lion’s share of scarce memory resources?

AI Tax and the new memory scarcity

We reframe the debate away from vague “distribution network problems” to a policy problem that is redistributive by design. The shift of foundry and packaging priorities toward high-bandwidth, high-margin memory for AI servers is not a temporary hiccup; it is a market decision with distributional consequences. Major memory makers are consciously steering their capacity and product roadmaps to meet demand from cloud and AI vendors. That choice raises the effective price of commodity DRAM and DDR5 modules that schools, households and small labs buy. For practical purposes, the market is imposing a new cost on education: higher per-device procurement costs, slower refresh cycles, and fewer options for low-cost computing labs. This is why calling it an “AI Tax” is useful — it captures the predictable transfer of scarce hardware value from broad public use into a narrow industrial application.

The evidence is clear on scale. Market trackers and industry briefs documented a sharp and sustained rise in memory pricing through late 2025, and market-research firms revised their forecasts upward in early 2026. The upshot is that commodity memory, which once kept mid-range machines affordable, now commands prices that push entire system budgets higher. Schools that planned three-year refresh cycles are now delaying or cancelling orders; districts with thin capital budgets face longer device lifespans, which lead to slower software adoption and weaker learning outcomes. These are not abstract supply-chain effects: they are concentrated harms to communities that depend on scheduled, predictable hardware replacement to keep students online and empowered.

Because capacity cannot be expanded overnight, the structural response from memory suppliers will be gradual. Foundry and packaging steps that support HBM and server-grade DDR require capital and lead time measured in quarters and years, not weeks. Meanwhile, cloud and hyperscalers are bidding heavily and locking supply through multi-quarter contracts. The bidding and allocation dynamics will keep upward pressure on consumer-facing prices long enough to shape school procurement cycles for at least two years. The practical consequence is that every procurement decision now embeds a macroeconomic bet: pay up for current availability, or wait, knowing that waiting may not bring lower prices if server demand stays high. That choice reshapes access: short-term purchases will favor well-funded districts and departments, creating a widening gap in practical computing access that compounds other digital divides.

What the AI Tax means for education and access

Short sentences matter because decisions must be made clearly. First, the immediate effect is an upgrade freeze. District and university buyers report postponing orders and trimming spec targets. Those freezes result in two harms: fewer devices per student and older machines that cannot run up-to-date educational software or tools. For computer literacy, computational thinking and hands-on STEM work, older machines are not simply slower; they constrain what teachers can assign and what skills students can practice. That erosion is invisible until a cohort arrives at a lab and finds the software cannot run. The “AI Tax” thus functions as a stealth curriculum knife.

Second, the cost shift affects software and cloud strategies. Schools that expected to offload heavy workloads to the cloud now face higher cloud pass-through costs because providers have absorbed higher capital costs. Higher server-side memory costs raise the marginal cost of hosted simulations, data science labs and adaptive training platforms. For schools already balancing licensing fees against hardware investments, the math changes: do we pay more for cloud services that keep older local machines running, or do we invest in better endpoints and reduce recurring service budgets? Neither choice is attractive for budget-limited districts. The tactical responses we are already seeing vary: extended device lifespans, conservative software rollouts, and a move toward lightweight web apps that run in low-memory environments. Each workaround is a second-best solution.

Third, inequity amplifies. Well-funded universities and private schools can hedge against the AI Tax by buying early, stockpiling inventory, or contracting directly with suppliers. Public systems and community colleges face procurement rules, budget cycles and constrained cash flow. The result is geographic and socioeconomic stratification of computing capability that resembles earlier eras—when home computers were rare and specialized labs were the gateway to coding and computational careers. If left unchecked, the AI Tax will recreate that old pattern: those with money get the machines that teach the future; those without become passive consumers. This is not inevitable. It is a policy outcome we can prevent through aligning procurement, subsidies and industrial policy with educational priorities. The next section lays out concrete policy steps.

Policy prescriptions to blunt the AI Tax

First, intervene where market allocation skews public interest. Governments and consortia can prioritize memory capacity for educational and public-interest computing using targeted purchase agreements, strategic stockpiles and capital grants. A practical step is to set aside periodic allocations of commodity DRAM for public institutions via negotiated allotments with major suppliers. Such allotments need not be large to be effective; even a fraction of a supplier’s quarterly consumer-module production can stabilize school procurement pipelines and lower volatility for public buyers. This is a classic market-shaping intervention: use collective buying power to reduce transaction costs and prevent thin-pocketed buyers from being priced out. It is not charity; it is public infrastructure policy.

Second, subsidize endpoint fairness rather than subsidize cloud bills. Many proposals intend to expand cloud access to compensate for weak endpoints. That can work in part, but cloud services will transmit the AI Tax downstream as server and memory costs rise. A more durable approach is targeted device subsidies and rotating upgrade funds for disadvantaged districts. These funds should be conditional on device-standard parity—guarantees that students have devices capable of running up-to-date educational software for the intended curriculum. A rotation model that replaces a fixed share of devices each year reduces the shock of a single large purchase and removes the incentive to postpone upgrades indefinitely.

Third, promote memory-efficient pedagogy and software standards as transitional tools for funding. Encourage edtech vendors to adopt low-memory modes and progressive enhancement designs so that core learning tasks do not depend on the latest hardware. This can be spurred through procurement standards and grant conditions. Simultaneously, fund transitional hybrid solutions—modest local compute appliances that use efficient accelerators or pooled labs that share modern hardware across districts. These interim measures buy time while longer-term industrial responses come online.

Fourth, rethink industrial incentives. Public policy should encourage a diversified memory supply chain and buffer capacity for consumer- and education-grade DRAM. That can include targeted incentives for fabs to maintain a share of commodity memory lines, support for packaging lines serving consumer modules, or R&D tax credits that reduce the cost of producing mainstream memory. Policymakers should also insist on transparent allocation practices when suppliers prioritize one customer segment; transparency enables public institutions to plan and respond.

Anticipating critiques, four lines of rebuttal are important. Some will argue that market forces must decide and that interventions distort efficiency. Yet education is not an ordinary consumer good; it is a public good with long-term social returns. Left to pure market allocation, we risk underproviding a service whose value compounds across decades. Others will argue that memory supply will expand and prices will settle. That may happen eventually, but lead times for fabs and packaging are long; in the meantime, cohorts of students will have lost critical learning opportunities. A third critique is fiscal: funds are scarce. That is real. But the alternatives—diminished skill pipelines and higher future social costs—carry larger long-term fiscal burdens. Finally, some may worry about gaming the system. Design allotments, rotation funds and procurement standards with clear audit and sunset clauses to limit rent-seeking. In short, legitimate concerns can be addressed; paralysis would be the far worse choice.

A practical call

The AI Tax is a simple reality: memory is scarce, prices are spiking, and the burden falls on those least able to pay. We can treat this as a market problem or a public policy issue. If we do nothing, the next few years will widen the difference between students who learn to build and those who merely consume. If we act, three modest moves will change the trajectory: coordinate buying power for public institutions, subsidize device parity not just cloud access, and impose disclosure and targeted incentives across the memory supply chain. These steps are practical, politically viable and, crucially, time-sensitive. The clock is not on an abstract market cycle; it is on school boards, budget cycles and the lives of students who may miss the computational foundations of future careers. The AI Tax can be paid voluntarily—through careful, equitable policy that spreads the cost and preserves access—or it can be paid involuntarily, through lost opportunity and entrenched inequality. We should choose a policy.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AOL. (2026). AI data centers are causing a global memory shortage. AOL Technology.

CNBC. (2026, January 10). Micron warns of AI-driven memory shortages as demand for HBM and DRAM surges. CNBC Technology.

Counterpoint Research. (2026). Memory prices surge up to 90% from Q4 2025. Counterpoint Research Insights.

Popular Mechanics. (2026). Why AI is making GPUs and memory more expensive. Popular Mechanics Technology Explainer.

Reuters. (2026, February 2). TrendForce sees memory chip prices rising as much as 90–95% amid AI demand. Reuters Technology.

Reuters. (2026, January 22). Surging memory chip prices dim outlook for consumer electronics makers. Reuters World & Technology.

Scientific American. (2026). The AI data center boom could cause a Nintendo Switch 2 memory shortage. Scientific American.

Tom’s Hardware. (2025). AI demand is driving DRAM and LPDDR prices sharply higher. Tom’s Hardware.

TrendForce. (2026). DRAM and NAND flash price forecast amid AI server expansion. TrendForce Market Intelligence.

Comment