When Policies Push Factories Over the Border: How Misaligned Climate Policy Creates Carbon Leakage

Input

Modified

Misaligned climate policy shifts emissions across borders instead of cutting them globally Uneven rules push firms to relocate production rather than invest in deep decarbonisation Only coordinated incentives can stop carbon leakage and restore policy credibility

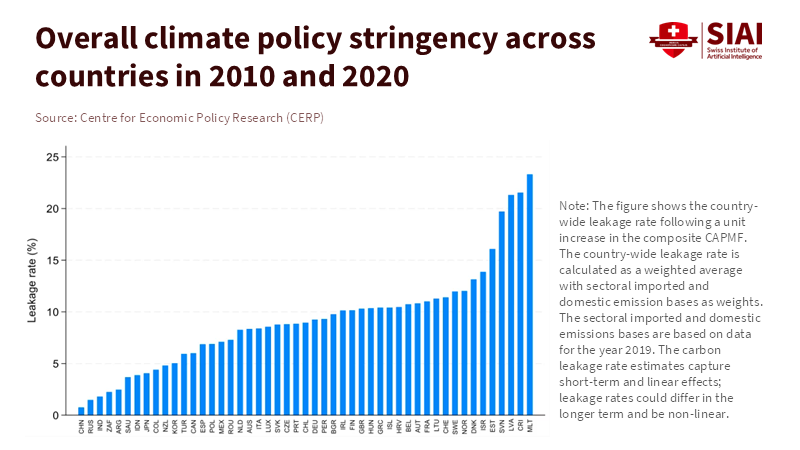

Think about this: about 25% of the emissions from energy-intensive goods traded worldwide from 2005 to 2020 can be linked to carbon leakage. This means emissions move from one country to another. It's not just an accounting trick; it's what happens when climate policies, business support, and trade rules don't align. Imagine a factory in Germany. It now faces a substantial new fee for its emissions. However, a similar factory elsewhere doesn't incur that cost. According to Clean Energy Wire, there are concerns that German factories producing goods such as steel or chemicals could relocate operations to countries with weaker emission regulations, which is why the European Commission has approved a 6.5 billion euro scheme to discourage this practice, known as “carbon leakage.” When climate policies are all over the place – some countries have strict rules, others don't – it doesn't just move emissions around. It changes the whole game: supply chains get shuffled, investments go to different places, and people start to lose faith in climate policy. If we actually want to cut emissions worldwide, countries need to work together, not just come up with strict rules on their own.

Why Conflicting Climate Policies Lead to Emissions Shifting

Climate rules are a mixed bag. Some countries tax carbon emissions directly, while others use carbon trading systems. Others use subsidies or weak regulations. These differences hit businesses hard. A manufacturer in Germany, with high carbon fees and strict rules, will see its costs go up. But their competitor in a country with lower fees won't.

So, businesses do what makes sense: they invest where it's cheapest or move the dirtiest parts of their production to countries with weaker rules. This isn't just a theory. Studies show that companies will merge or invest abroad to relocate production to lower-cost locations when environmental regulations differ. It often starts small – moving one production line, outsourcing a part, or opening a new factory in another country. However, the result is clear: the country with the strict rules appears to be cutting emissions, but emissions are just higher elsewhere because it's importing from that country. It is not clear whether the world is any better off.

The politics of this exacerbate the situation. People see factories closing and jobs disappearing. They begin to push back against stringent climate regulations. Businesses say they can't compete without special treatment. Politicians respond by giving them breaks, free credits, or financial aid. That weakens the climate rules and creates unfair advantages. Ultimately, pursuing ambitious climate targets becomes a political mess that weakens the effort to reduce emissions. That's why rigid rules at home, without international teamwork, can backfire. They might lower emissions in one country but not worldwide, and sometimes they even increase them globally.

How We Know Emissions Are Shifting: The Evidence

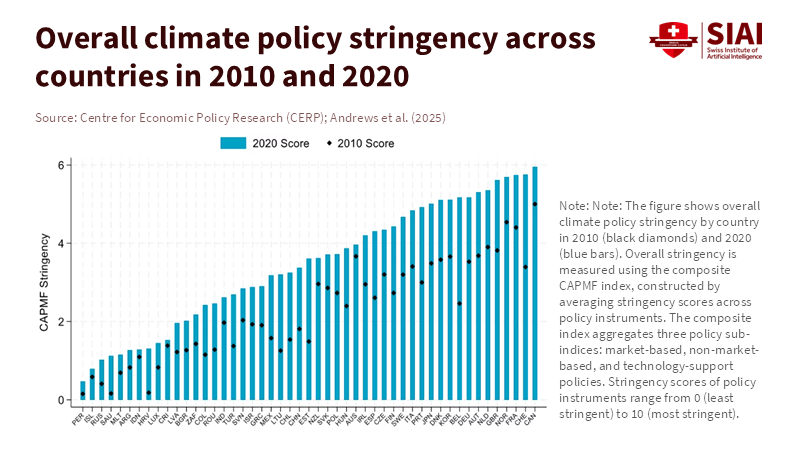

We're getting a clearer, more detailed look at this problem thanks to new data. The OECD's report on carbon rates shows that in 2023, only a few emissions worldwide faced high carbon costs. In the countries studied, only about 27% of emissions were covered by carbon pricing mechanisms (e.g., taxes or trading). At the same time, studies of specific industries and trade patterns indicate that emissions are indeed shifting. According to an OECD report on the EU's Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), carbon leakage in manufacturing is a concern. Still, the study does not provide specific leakage rates for energy-intensive goods between 2005 and 2020. According to ETLA research, the EU Emissions Trading System has led to lower emissions in the EU but has also increased carbon intensity in imports, indicating that carbon leakage has occurred in some industries. However, this does not mean that all regulations have the same effect. They demonstrate that the risk of emissions shifting is real and measurable.

Here's how these leakage estimates are made: Researchers look at (1) how much of the economy is covered by carbon pricing and how high those prices are, using data from the OECD; (2) how changes in production in one country are related to changes in imports from other countries; and (3) studies that track companies or industries to see when they move production or outsource it to other countries. If good data is unavailable, they use conservative estimates. For example, if a country's production of something goes down while imports rise, and global production is enough to meet demand, they assume emissions have been shifted abroad. This guarded approach avoids exaggerating the problem, but it still shows that when policies and prices differ, it encourages companies to shift emissions to other countries.

Research on this is not entirely consistent. Some studies suggest that regulations push companies to be more creative, leading to cleaner processes and better exports. Others show companies merging, moving factories, and changing supply chains to take advantage of weaker environmental rules. Recent work also shows that companies relocate only the dirtiest parts of their production, which can obscure the problem if one looks at the number of factories. What happens depends on the industry, the product complexity, the global scope of the supply chain, and the extent to which carbon prices differ across countries. But the basic story stays the same: if costs are different enough, companies will move emissions to where it's cheaper.

Solutions That Work: Make the Rules Consistent

If emissions shifting is caused by policy differences, then the answer is to close those gaps. That doesn't mean every country has to have the same taxes or carbon limits. It means making it less desirable to move carbon-intensive production to avoid regulations. One way to do this is with border adjustments – a tax or credit that takes into account the emissions associated with goods being traded – along with a real carbon price at home. The CBAM pilot has already shown that being clear about border rules reduces uncertainty and can discourage companies from moving by leveling the playing field for imports. Another way is to help companies adapt with financial support and job training. When companies face higher costs, well-designed subsidies for low-carbon investments or temporary aid linked to actual emission cuts can keep jobs and investments at home while pushing for real reductions.

How the policies are designed is essential. Giving blanket exemptions encourages companies to game the system. A report from the OECD notes that governments have used both permanent and temporary support measures during the energy crisis. Still, it does not explicitly compare the effects of broad, permanent financial aid with those of temporary, conditional support tied to emission reductions. It's also important to track things carefully. It's easier to see emissions shifting when policymakers track emissions from imports and company investments in real time. This requires better data on industries, consistent emissions accounting across countries, and stricter rules for companies to disclose their multinational investments.

Finally, countries should coordinate their rules with trading partners when possible. Multilateral deals don't have to solve everything, but even modest steps towards coordination among big economies can reduce the worst incentives.

It's essential to think about the criticisms of these ideas. Some will say that strict rules at home, along with policies that encourage innovation, will eliminate emissions shifting in the long run. That might be true in some industries, especially where green technologies are taking off. But it's not always the case. If the dirtiest production steps are still expensive and can be easily moved, different rules will still tempt companies to relocate.

Others will argue that border measures are protectionist. That's a valid concern if the measures are unclear or set at unfair levels. However, well-designed border adjustments use verified emissions data and fair pricing to even out costs, rather than protecting domestic businesses from competition. According to an OECD analysis, making climate rules consistent and clear is as important as protecting local industries when addressing emissions shifting. If about a quarter of emissions from traded goods result from shifting emissions abroad, climate policy must look beyond domestic reductions to be effective. It has to cut emissions globally. Climate policies that aren't aligned fail that test. They shift emissions and erode public support. They create a political climate where it's better to get an exemption than to be ambitious.

Policymakers should stop treating emissions shifting as a minor technical issue and start seeing it as a key design factor. That entails aligning incentives across borders through transparent border adjustments and conditional support, and building systems to spot early emissions shifts. If we do both, strict rules at home can become credible ways to reduce global emissions. If not, we'll keep on playing a shell game where we lower emissions in one place only to see them pop up somewhere else – a game that the climate can't afford.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bruegel. (2024). How to fill the remaining gaps in pricing the emissions of the EU’s energy-intensive industries. Bruegel Policy Brief.

Choi, J., Hyun, J., Kim, G., & Park, Z. (2023). Trade policy uncertainty, offshoring, and the environment: Evidence from US manufacturing establishments. IZA Discussion Paper.

Dechezleprêtre, A., et al. (2017). The impacts of environmental regulations on trade, employment and location. Review of Environmental Economics and Policy.

New Climate Institute. (2025). Navigating CBAM in China. Report.

OECD. (2023). Effective Carbon Rates in 2023. OECD Publishing.

OECD. (2025). The potential effects of the EU CBAM along the supply chain. OECD Report.

Saussay, A. (2023). International production chains and the pollution offshoring hypothesis. Resources, Conservation and Recycling.

Santa Fe Institute. (2026). Climate policies can backfire by eroding “green” values, study finds. SFI press release.

Wang, M., et al. (2024). Trade flows, carbon leakage, and the EU Emissions Trading System. Journal of Environmental Economics.

(News) Euronews. (2026). ‘That ends now’: German court ruling raises pressure to fix stalled climate plans.

(News) Anadolu Agency. (2023). Thousands take to the streets in Germany demanding climate action.

Comment