Sun-First Strategy: How “solar-first development” is changing growth math for middle-income countries

Input

Modified

Cheap solar has reshaped the growth logic for power-scarce economies Solar-first strategies deliver faster, cheaper energy than nuclear in most cases today The challenge is timing: build solar now and scale complexity only when demand rises

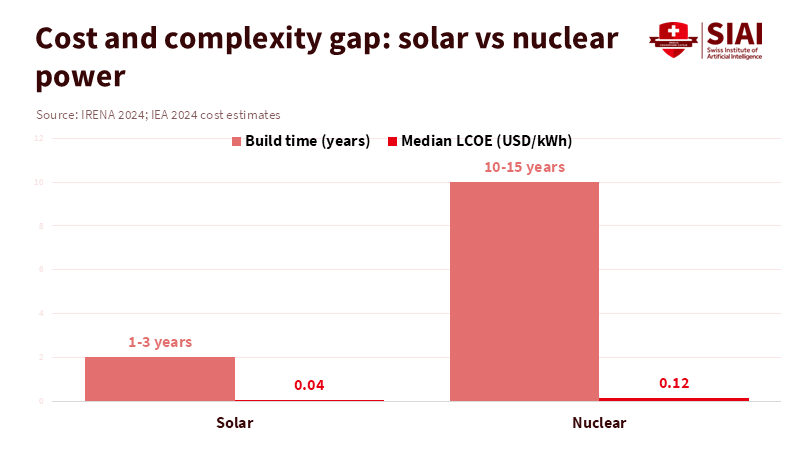

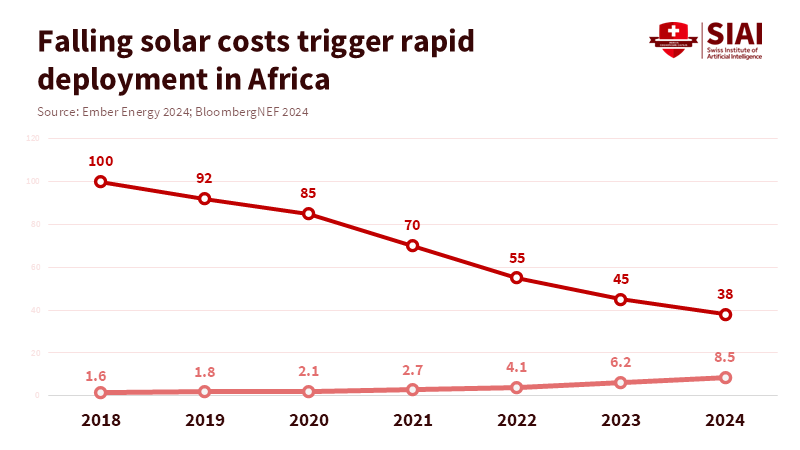

Here's a key point that should change our talks about energy and growth: the average global cost of large-scale solar power has dropped to around $0.043 per kWh in 2024. This makes new solar one of the cheapest energy sources out there. This isn't just about lower bills; it changes how countries that can't afford or don't want to deal with the difficulties of nuclear power approach investment, industry plans, and global influence. According to the World Nuclear Industry Status Report, wind and solar facilities produced significantly more electricity than nuclear power in 2024, suggesting that if governments have access to affordable and easily deployable solar systems, investing in expensive nuclear reactors may not make economic sense. Instead of debating whether green policies hinder growth, the key question should be when prioritizing solar leads to faster, cheaper, and fairer growth compared to nuclear options. Many middle-income countries facing power shortages now need to consider this urgently. The question is simple: which method provides more reliable power to businesses, hospitals, and schools at a price and timeline that governments can manage?

South Africa and the proof in plain sunlight

South Africa is a real-world example of the solar-first idea. They've rapidly increased their solar power capacity over the past five years, adding about 7 gigawatts. According to the International Energy Agency, Africa is experiencing double-digit growth in both utility-scale and distributed solar photovoltaics, driven by the continent’s abundant renewable resources and declining technology costs. The private sector, including businesses, mines, and rooftop systems, is leading much of this expansion. For a country that has struggled with power cuts, the benefits are clear: fewer outages, less diesel use, and reduced disruption for businesses. The idea for decision-makers isn't complicated. It's a question of cost: building a new nuclear plant is expensive, takes a long time, and entails foreign exchange and long-term risks. Solar systems, on the other hand, can be set up in months, use readily available parts, and create jobs and business for local companies. If there's a low-cost, fast option that meets most current needs, it makes sense to choose it rather than risk future budgets on unnecessary, expensive capacity that might not be needed for years.

There's also a lesson here about simplicity. Nuclear projects require rigorous quality control, tightly integrated supply chains, and skilled teams that take years to develop. That might make sense for rich countries seeking energy independence or military advantages. It's not a good fit for countries that can't handle the costs of long-lasting, expensive reactors. Solar power, with its panels, inverters, local installers, and battery systems, is much easier to integrate into existing markets. This results in faster adoption and quicker benefits. This is also important for equity: households and small businesses can benefit directly from solar, without having to wait for improvements to the power grid. The main idea is that for many countries today, choosing solar first isn't a second-best option; it's the quickest way to get power that's affordable, reliable, and locally available.

Why the cost curve flips the growth argument

The old idea that green policies hurt growth because they raise costs was based on the fact that clean technologies are expensive. But that's no longer the case with solar. After years of growth, the cost of large-scale solar has fallen to levels that surpass those of fossil fuels and many other low-carbon options. In 2024, the average global cost of solar was around $0.043/kWh. In China, it was even lower. These cost differences can really change things. When power becomes cheaper, it removes the energy constraints that once constrained manufacturing and other service industries. Businesses cannot remain open longer, invest in new equipment, and avoid using expensive diesel generators. People can study in the evenings and start small businesses. The end result is growth, not the opposite.

It's important to understand what these numbers mean for policymaking. The cost of electricity isn't the only thing to consider—grid integration, storage, and reliability are also important. However, two factors are reducing these concerns: first, batteries and system integration have become much cheaper, making solar-plus-storage a viable option; second, smaller projects reduce the need for large upfront payments. Together, these changes transform solar energy from an unreliable resource into a dependable one. Nuclear power remains useful for continuous, high-capacity power, such as large industrial areas with constant demand. According to a recent report, Africa has significant potential for renewable energy, particularly solar power, thanks to its abundant sunlight and vast desert areas. Focusing on solar energy can help developing countries address immediate power shortages, whereas larger plants such as nuclear power should be considered only when there is a clear, long-term need. The country is ready for it.

China, supply chains and the geopolitics of cheap panels

The rapid price cuts that are making solar-first development possible aren't just luck; they're the result of planning and expansion. China created a manufacturing base for solar panels, batteries, and other components. This effort, combined with logistics and financing, filled markets with cheap panels and batteries. This has made it easier for Africa and other developing regions to access affordable electricity. In the year ending June 2025, African imports of solar panels increased by 60 percent, indicating that supply is meeting demand. The key is that equipment costs have fallen worldwide, so local policies should focus on establishing installations, training workers, and facilitating financing rather than attempting to build local manufacturing that is difficult to establish.

This raises worries about. Cheap Chinese exports can create trade imbalances and concentrate manufacturing in one country. This creates risks such as commercial disruptions or political issues. But asking poor countries to wait to get electricity until they can build local factories isn't fair. The practical solution is for countries to obtain affordable equipment now, while also using policies such as tariffs, industry groups, training programs, and partnerships to capture more of the local value over time. Use imports to address today's problems, but develop a plan to capture greater value from local installation, maintenance, and recycling. This balances current needs with future goals.

The case for solar-first also relies on speed. Renewable projects can be approved, funded, and built much faster than reactors. In many places, the time required to provide power to businesses is measured in months. According to the World Nuclear Industry Status Report, prioritizing lengthy reactor projects to address immediate challenges can lead to continued delays, whereas prioritizing solar development is not about dismissing large-scale technology but about focusing on faster implementation and shorter lead times. Nuclear power should be considered only when there are clear signs of demand and financial and institutional readiness.

Concrete policy iconsequences foreducators, administrations and funders

For education leaders, the implications are clear: solar-first makes it easier to get electricity to schools at a low cost and quickly. This changes priorities for grants, making rooftop solar, campus microgrids, and battery-powered classrooms more valuable. Training programs mustfocus on installation, operations, and maintenance skills. According to the Midwest Renewable Energy Association, providing education on electrical assembly, battery safety, and grid integration is an important strategy for growth. Administrators should focus on designing processes that prioritize practical projects and on developing funding opportunities for schools and small businesses that implement solar-plus-storage systems. For international funders, the goal is to shift funds toward smaller projects and technical support for grid management, not just toward a few large reactors that absorb guarantees for years.

Some criticisms are expected. People will say that solar can't provide a steady power supply for industry or that cheap imports hurt local manufacturing. These points are true, but miss the point. Solar-first doesn't prevent investment in heavy power later if needed. It does require effort to move the installation and services locally. Others may say that solar benefits richer businesses first. Officials must design subsidies to avoid inequality: grants for health centers, schools, and microgrids can guarantee broader benefits. These are political problems, not technical ones. Evidence shows that cheap solar is already boosting production where it's used, and that policies can expand those benefits if governments act.

From diagnosis to demand: sequencing national plans

Countries should organize policy steps around three priorities. First, quickly fix power shortages: set up solar and storage where outages are most damaging, like at hospitals and industrial parks. Second, invest in skills and regulations so that installation and grid management can expand quickly. Third, keep other options open: plan for larger capacity only when growth and financial readiness are clear. This respects both cost and job creation. This also matches the evidence: markets are importing solar panels, battery costs have dropped, and they report fewer outages. The right plan treats cheap imports as a public benefit while building local capability where it makes sense.

Doing this will require new tools: financing for community projects, quick approvals for microgrid projects, and help to turn imports into local jobs. International partners should shift away from funding single projects toward smaller ones that create jobs. For education, the benefits are obvious: nighttime learning, classrooms, and lower bills that free money for teachers. These are classic multipliers.

To summarize, the argument against green policy is now outdated, given the availability of low-cost solar. According to the International Energy Agency, solar power is expected to become the largest source of installed electricity capacity in Africa by 2040, surpassing both hydropower and natural gas, which suggests that prioritizing solar development can provide a faster and more cost-effective way to meet energy needs while still leaving room for nuclear energy in the mix. It means that governments should choose the option that best fits current demand and capacity. The numbers favor solar-first for most countries; policy should follow. To conclude, planners, donors, and educators have to update investment rules and training to reflect a solar-first approach. Emphasize projects that deliver power quickly, expand installation training, and design financing mechanisms that bring these options to schools and clinics. Do this, and affordable power will stop being merely a goaland start producing results.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Ember. (2025). The first evidence of a take-off in solar in Africa. Ember Energy.

International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). (2025). Renewable power generation costs in 2024. IRENA.

International Energy Agency (IEA). (2025). Breakthrough Agenda Report 2025: Power. IEA.

RatedPower. (2025). South Africa’s 12% solar power surge in a challenging energy landscape. RatedPower blog.

Reuters. (2025). China's solar power capacity growth and market reforms. Reuters.

Financial Times. (2025). The rise of China's electrostate and global clean-tech impact. Financial Times.

Bloomberg. (2026). Africa's solar capacity seen rising after record 2025 growth. Bloomberg.

Comment