Why SFDR Needs More Than Just Talk: A Plan for the Market

Input

Modified

SFDR has increased disclosure, but it has not shifted capital in a meaningful way Europe’s sustainable finance rules prioritize paperwork over market consequences Real reform must link sustainability claims to enforceable financial incentives

Europe accounts for about 85 percent of global sustainable funds’ net assets, amounting to almost €2.2 trillion by the end of last year, according to a study by the Association of the Luxembourg Fund Industry, Morningstar, and Tameo. However, these regulations have yet to significantly shift investment risks or direct more capital to where it is most needed. This isn't just a minor problem; it's a significant policy mistake with real-world consequences. When the rules about what companies have to tell us become a confusing array of categories and checklists, the market can't reward companies that are actually making a change or punish those that are falling behind. According to the Commission de Surveillance du Secteur Financier (CSSF), the SFDR was designed to provide investors with better information on sustainability, but in practice, it has required extensive data collection and reporting by investment fund managers. They complete forms, change the names of their funds to keep up with the changing rules, and continue operating as usual. If we want sustainability to make a real difference in investment portfolios, we need to stop acting as if simply telling people is enough. We need to start using rules that have real teeth and can move the market. This article argues that SFDR failed because it placed excessive emphasis on paperwork and insufficient emphasis on penalties. It also lays out a plan to fix SFDR so it can effectively allocate funds where they are needed.

Why just telling people things hasn't changed the market: the real-world failure of SFDR

The idea behind SFDR was simple: if companies have to disclose their sustainability practices, the market will take that information into account when deciding how much they're worth. But that only works if the information is clear and the market is paying attention. In reality, neither of those things happened. Companies can disclose a lot of information without making any fundamental changes to their investments. Investors, confused by all the different categories and standards, often ignore the disclosures or misunderstand them. According to a 2024 article in IESE Insight, although the SFDR has some flaws, it appears to be associated with a reduction in carbon emissions across the portfolios of European investment funds subject to these disclosure rules. According to research by Giacometti and colleagues, companies with high levels of market-implied sustainability have outperformed financially from 2010 to 2023; however, the evidence does not indicate significant price changes or persistent effects attributable solely to SFDR fund labeling. Where different datasets give varied results at the fund level, a general direction is reported when there is consensus. I will also use publicly available aggregate statistics, such as fund flows and asset totals, to avoid overstating precision.

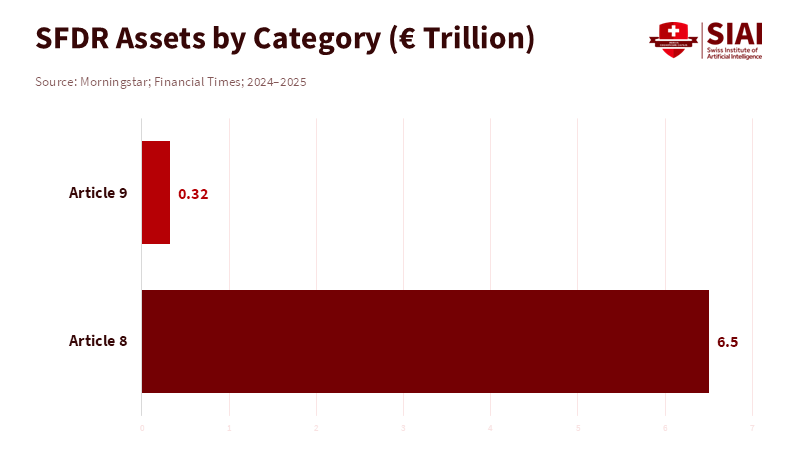

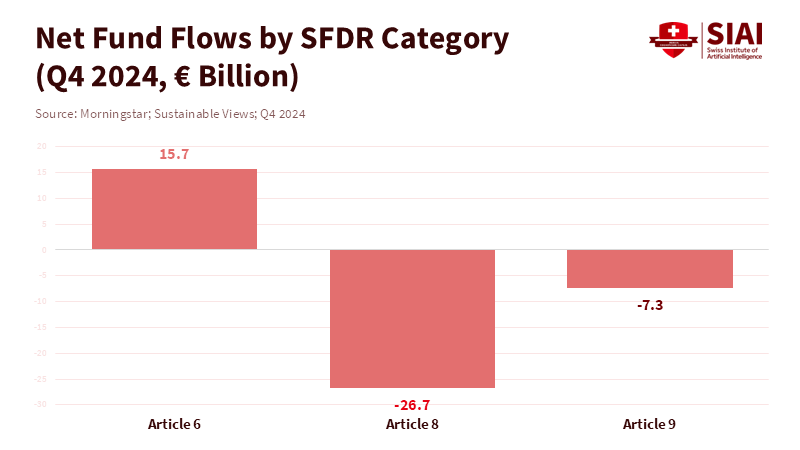

When a law fails to affect the market, it's more than a technical issue. It causes problems for policy in two ways. First, it erodes public confidence in the system. According to a Morningstar report, if investors come to believe that Article 8 or Article 9 labels do not guarantee a fund's sustainability, trust in such claims could decline, as evidenced by the €26.7 billion withdrawn from Article 8 funds in the last quarter of 2023. Additionally, this situation might also result in wasted political effort. According to a report from the Maples Group, the number of sustainability-focused funds in Europe has increased by 24 percent over the past year, and assets in these funds now exceed €6 trillion, suggesting that regulations such as the SFDR are having a notable impact on investment allocation. To put it simply, if SFDR reform continues to treat disclosure as the solution, we'll keep going in circles: new labels, more paperwork, and only superficial changes to fund names.

What the evidence shows—and what politicians have already admitted about SFDR reform

Any realistic SFDR reform needs to take into account three key facts. First, even though there's substantial capital in sustainable investments, that growth hasn't necessarily led to more sustainable portfolios. Sustainable assets in Europe had huge sums by the end of last year, but studies show that the labels haven't led to significant improvements in portfolio greenhouse gas footprints. Second, compliance with the rules has been costly, and investment managers have often responded by simply renaming their funds rather than making fundamental changes. Thousands of funds were renamed or relabelled in the years after SFDR came out. Third, regulators and industry groups both acknowledge that the framework needs to be simpler and better aligned with market practices if it's going to be useful. These aren't controversial points; they come from market reports, industry feedback, and independent research. Taken together, they suggest that a system that focuses on disclosing extensive information can create the illusion of progress without actually shifting the market in a way that supports the transition to a low-carbon economy. Where public reports provide estimates for compliance costs or total assets, I will reference those figures. However, when recent research on causal impacts is debated, such as the effectiveness of the SFDR, I will highlight the overall direction supported by experts; for example, a recent study by Allcott and colleagues found that the SFDR had little effect on fund flows or portfolio sustainability.

This evidence is essential for educators, administrators, and decision-makers in different ways. Educators need to teach finance professionals to see sustainability disclosures as just one piece of the puzzle. While they're helpful for transparency, they're not enough to create real impact. Administrators of public pension funds and university endowments should require that investment managers meet specific sustainability goals, not just complete disclosure checklists. Policymakers should view the admission that SFDR hasn't had much impact on the market as an opportunity to redesign the rules. Instead of focusing on even more detailed disclosures, they should focus on making the rules more focused on what can be measured and enforced.

Principles for an SFDR reform that works for the market: enforceability, simplicity, and market signals

If the goal is to move capital, SFDR reform needs to change three things at once: ensure that sustainability claims can be verified, that penalties are appropriate and credible, and that product categories are easy for investors to understand. To make claims verifiable, we need standardized, auditable metrics that go beyond allowing companies to claim sustainability. A fund that claims to be a transition fund, for example, should demonstrate that a certain percentage of its investments are in assets that support the transition to a low-carbon economy. A third party should verify this, and supervisors should be able to audit portfolio-level metrics. Simplicity means fewer, clearer categories with specific requirements. The labeling rules should be easy to understand for both a regular person saving for retirement and a manager of a huge pension fund. Finally, market signals are necessary: when a fund uses a sustainability label, supervisors should be able to impose financial consequences if the fund fails to meet the requirements. This could include higher capital requirements for misreporting, fines for greenwashing, and restrictions on using sustainable in product names if the thresholds aren't met. These need to be practical reforms, not just token gestures. The law should change financial incentives, not just the words that companies use.

There are valid arguments against this approach. Some critics argue that more vigorous enforcement will increase costs for investment managers, reduce the number of available products, and shift activity to countries with less stringent regulations. These are real concerns. But the alternative—accepting a market where labels don't mean much—creates systemic costs by misdirecting capital and eroding investor faith. A well-designed system can reduce these trade-offs. We can set progression thresholds that increase gradually over time, allow exceptions for small managers during an initial period, and align definitions with other EU laws to avoid duplication. In the long run, transparent and enforceable rules reduce uncertainty. This firmness can lower the cost of capital for investments that genuinely support the transition to a low-carbon economy.

Practical steps: what an actionable SFDR reform looks like for practitioners and regulators

In practice, a credible SFDR 2.0 would include the following market-focused elements. First, three clear product categories—Sustainable (dark), Transition (amber), and ESG-Aware (light)—each with specific numeric thresholds for portfolio alignment and exclusions. Second, mandatory third-party verification for dark and transition claims, with a public list of verifiers and rules to prevent conflicts of interest. According to Eurosif, the report highlights the need for clear criteria and thresholds for SFDR categories, but does not outline any specific supervisory toolkit with escalating penalties or require mandatory quarterly updates and audits of portfolio-level KPIs. Fifth, precise coordination between SFDR oversight and financial supervisors to ensure that misreporting has real market consequences—for example, limits on marketing and distribution for non-compliant funds. These steps would change incentives: labels would only be valuable if they reflected fundamental portfolio changes.

How would these reforms affect those in education and fund governance? For program directors and course designers, the changes mean updating curricula to emphasize operational sustainability assessment—how to interpret KPIs, how to evaluate third-party verification, and how to link funding claims to real-world transition efforts. For trustees and administrators, procurement processes should demand verifiable action plans rather than just impressive ESG reports. For decision-makers, these steps require building capacity within supervisory bodies, designing appropriate penalties, and aligning metrics with other EU initiatives to prevent companies from exploiting loopholes.

The main problem with SFDR so far is that it treats transparency as a substitute for real consequences. A system that lets investment managers file paperwork while leaving the real levers of capital untouched won't build trust or drive the transition to a sustainable economy. SFDR reform needs to be designed to influence the market: clear categories, auditable metrics, credible penalties, and coordination across supervisors. This combination will force the shift from simply filing forms to actually changing portfolios. Education programs need to teach the tools for this shift; trustees need to demand it; and regulators need the resources to enforce it. If we want finance to deliver on its climate promises, we need to design rules that change incentives, not just paperwork. The market will respond when the rules make it expensive to fake it and profitable to do it right.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Allcott, H., Egan, M., Smeets, P., & Yang, H. (2026). Evidence from Europe’s Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation (working paper). National Bureau of Economic Research.

ALFI. (2024). European sustainable investment fund study 2024 (research report). Association of the Luxembourg Fund Industry.

European Commission. (2025). Monitoring capital flows to sustainable investments (report). Directorate-General for Financial Stability, Financial Services and Capital Markets Union.

FT. (2026). EU green rules fail to boost funds' ESG credentials, research finds (news article). Financial Times.

IIGCC. (2025). EU Sustainable Finance Disclosure Regulation overhauled: new review (insight/response). Institutional Investors Group on Climate Change.

Morningstar / Financial News reporting. (2025). Fund groups shelve 'dark green' funds as new launches hit record low (industry report/news).

Comment