When Capital Looks Real but Isn’t: How Synthetic Capital Quietly Undermines Resilience

Input

Modified

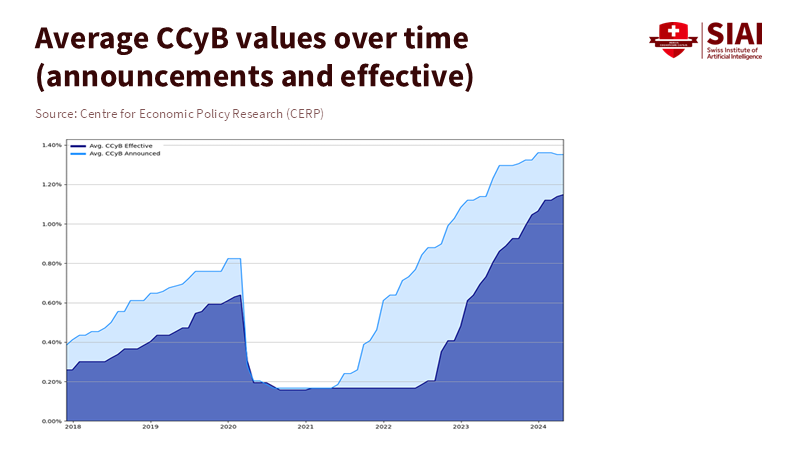

Banks increasingly meet capital rules with synthetic structures instead of real equity Derivatives and risk transfers weaken the power of countercyclical buffers Regulation now measures resilience on paper more than resilience in practice

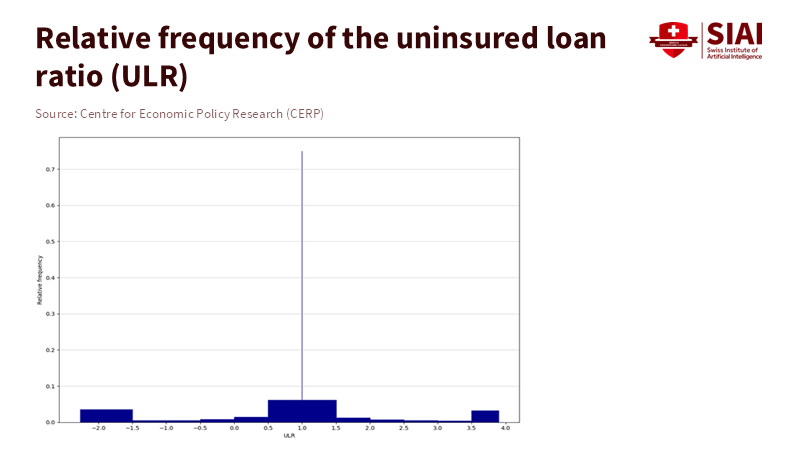

A one-percentage-point rise in the countercyclical capital buffer corresponds with a roughly 53 percentage-point fall in the uninsured share of affected loans. This is not because banks hoarded equity, but because they bought protection. That single, stark statistic tells a simple story. Regulators ask for more capital. Banks answer by creating synthetic capital through derivatives and structured transfers. These actions appear to reduce risk on paper, but do little to increase loss-absorbing capacity when the cycle turns. The result is the illusion of resilience. This matters for policy, supervision, and how we teach the next generation of finance professionals. If capital requirements can be met by insurance contracts and regulatory-eligible accounting tricks, macroprudential tools lose traction exactly when they are supposed to work best. The following argues that the right response is not cleverer accounting but clearer rules, tougher disclosure, and a curriculum shift. We should make “synthetic capital” a cautionary case study, not a loophole.

Synthetic Capital: The Illusion of Resilience

When regulators create rules about capital, their goal is to provide a buffer of time. Having larger buffers when times are good should soften the blow when the economy slows. This makes sense only if capital truly acts as a real safety net that can absorb losses. According to the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision, banks actively manage their capital levels to comply with regulations, often making short-term balance sheet adjustments to meet requirements.

Synthetic capital refers to methods by which banks reduce their apparent risk without actually improving their ability to withstand losses. This is usually done through instruments such as credit default swaps (CDS) and other synthetic risk transfer (SRT) instruments. Essentially, a bank replaces its actual balance sheet, which regulators can easily assess as safe or unsafe, with a paper-based transfer of credit risk. This raises an important question: Are we dealing with real financial instability, or simply managing how things appear on an accounting sheet?

This question is relevant because macroprudential policies are increasingly used worldwide. Regulators use tools such as the countercyclical capital buffer to manage credit cycles, making sure they are not too extreme. However, if market tools are used to circumvent these policies, the stabilizing effects of macroprudential measures are significantly weakened. Therefore, people training regulators, bank supervisors, and future bankers need to teach not only how to calculate capital ratios, but also how to interpret them. They also need to teach how these ratios can be manipulated, and how supervision must go beyond simply looking at the reported numbers. This means moving away from purely theoretical calculations and focusing more on real-world examples of risk transfers. Also, supervisors should read disclosures carefully and create scenarios that assume counterparties will fail or markets will collapse.

How Derivatives and SRTs Create Artificial Capital

The basic idea is quite simple. If a bank faces a higher countercyclical buffer, it has a few choices, which include raising equity, reducing risky lending, or insuring its exposures. By purchasing a CDS on a group of assets or using an SRT, the bank can reduce its risk-weighted assets because the reported exposure is partially insured or transferred. Analysis by the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), using data on CDS transactions and syndicated loans, shows that banks subject to higher countercyclical capital buffer rates increased their CDS hedging for loans in those areas. The estimated result is substantial, a 53 percentage-point decrease in the uninsured portion of the loans for every 1 percentage-point increase in the buffer rate. This suggests a focused response that is highly sensitive to policy. In short, the tools regulators use to make lending safer have a workaround: derivatives turn regulatory weight into tradable claims.

However, there are two important things to consider. First, hedging can be legitimate. Companies and banks often use derivatives to deal with real credit risk. Second, not every CDS purchase is intended to avoid regulation. Some are actual risk transfers that improve real stability. The problem arises when these actions are timed and structured mainly to meet the minimum rules, while still leaving the bank exposed to correlated stress. Often, these synthetic methods rely on complex legal and accounting structures to secure regulatory approval. When the parties involved in these SRTs are under pressure, the promised transfer of risk may not work or be less effective than expected, especially during widespread financial crises. Recent comments from experts suggest that SRTs need close attention because their economics can seem harmless on their own but can easily fall apart during a crisis.

Evidence, Limits, and What the Numbers Tell Us

The most compelling argument comes from comparing banks that are subject to different countercyclical capital buffer rules across countries and over time. The BIS study uses CDS data from EU trade repositories and syndicated loan data from November 2017 to April 2024 to show the extent of hedging activity when buffer rates increase. This period includes multiple policy cycles and the adjustments made to macroprudential tools after the pandemic, which strengthens the findings. Keep in mind the 53-percentage-point figure reflects hedging activity by banks most affected by the buffer increase and is a local treatment effect, not a global multiplier. Regardless, the evidence strongly suggests that eligible risk transfers are a primary way banks adjust to policy.

Other analyses and industry reports show how SRTs have changed. Experts highlight that modern SRTs can be customized, structured in tranches, or involve third-party protection sellers with varying credit quality. Volumes of SRTs may be small compared to the entire banking sector, but their strategic use around regulatory changes increases their impact. The market for synthetic capital doesn't need to be large to have an effect; it only needs to be well-placed to weaken the effects of capital buffers. This is why regulators should pay attention to both the amount and timing of these transactions.

Policy Suggestions for Supervisors, Educators, and Institutions

First, supervisors should limit what qualifies as regulatory relief. Risk transfers that lower capital requirements should face harder tests. They should be evaluated based on the strength of the counterparty, documented recoverability in stressful situations, and a residual risk metric that cannot be offset by just contractual promises. Essentially, eligible transfers should be considered additions to contingent capital only if they clearly enhance the ability to absorb losses in a severe but possible crisis. This requires simple-to-use metrics, such as a conservative assessment of counterparty exposure, a minimum protection period, and a disclosure form that shows counterparty correlation and the factors affecting the protected assets.

Second, disclosures need to be redesigned for clarity rather than obscurity. Public filings should show the uninsured portion of loans and how it changes with regulatory settings. Banks should provide scenario tables that show how SRTs perform under severe stress, including counterparty default, widening spreads, and sudden lack of liquidity. According to the ESRB handbook, supervisors are encouraged to provide anonymized summary statistics to support consistent comparisons across regions and enhance the practical relevance of training materials by including real examples. Educators can draw on these resources by incorporating disclosure forms and practical scenarios into their curricula, helping graduates distinguish between synthetic and real capital. Consistent reporting will make it more difficult to achieve technical compliance without true stability.

Addressing Concerns and Providing Solutions

A common argument is that derivatives and SRTs improve risk allocation, and banning them would be costly and reduce market efficiency. While derivatives play an important role, the goal is not to ban hedging. Instead, it should be to tax or limit regulatory relief from hedging unless it passes tests designed for systemic events. Another concern is that regulators lack the resources to oversee complex synthetic structures. I suggest international cooperation, standardized disclosure forms, and simple tests that focus on key indicators like the uninsured share, counterparty concentration, and the proportion of protection from non-bank sellers. Focusing on a few reliable checks can greatly improve credibility and result in effectiveness.

There is also the concern that academics and educators cannot solve regulatory arbitrage on their own, which is true. However, better training can change norms. If bankers expect synthetic solutions to be tested under stress, they will be less likely to rely on regulatory engineering than on building equity or on conservative lending practices. Changing the curriculum to include case studies, registry data, and supervisory datasets can shift behavior over time and is a practical way to create lasting change.

Close the Loophole and Teach the Lesson

The data show that when buffers increase, banks often respond by protecting their assets instead of increasing paid-in capital. This approach preserves lending in the short term but creates a fragile stability that can collapse under widespread financial stress. The solution is to redefine transfer eligibility, require scenario disclosures, and revise education so that future practitioners and supervisors can distinguish between real safety nets and synthetic ones. Capital requirements are meant to provide time to react during a downturn. Regulators must ensure that these buffers are composed of capital that functions when needed, not contracts that expire or fail when the cycle turns. Make synthetic capital visible, expensive, or ineligible; teach it as a case study; and require stress-tested metrics. Otherwise, macroprudential rules risk becoming a paper shield against a very real fire.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Aldasoro, I., Barth, A., Comino Suarez, L., & Reale, R. (2026). Banks and capital requirements: evidence from countercyclical buffers. BIS Working Paper No. 1323.

CFA Institute. Ricciardelli, A. (2026, January 13). Synthetic risk transfers are the talk of the town. But are they as scary as they look? Enterprising Investor.

All Banking Jobs. John Wick. (2026, January 23). Derivatives hedging can weaken effect of capital rules – BIS paper.

Comment