When Data Skips a Key Variable: Rethinking femicide drivers in Europe

Input

Modified

Femicide risk is misread when key population variables are left out Missing data distorts which policies appear to work Better models are needed to target prevention effectively

Here's something that should make us rethink our approaches to understanding femicide: In 2023, it's estimated that around 140 women and girls were killed every day by someone they knew—a partner or family member, across the globe. This number comes from the UN and other groups, who improved how they gathered data and realized they had been missing many victims before. This isn't just a small change in the numbers; it's a big deal. If improving the way we count can increase the global death toll by thousands, then leaving out important social factors in our models can lead us to make the wrong decisions about how to help. In Europe, femicide rates differ from one country to another, and there are clear differences between Eastern and Western Europe. Because of this, we must include important local factors—how well people are integrated into society, where migrants live, and cultural attitudes within groups. If we don't, we risk not stopping femicide the right way and making political tensions worse. We need to think of femicide drivers as a problem of data and how we analyze it, not as something we can simplify for political reasons.

Rethinking the rural–urban assumption about femicide drivers

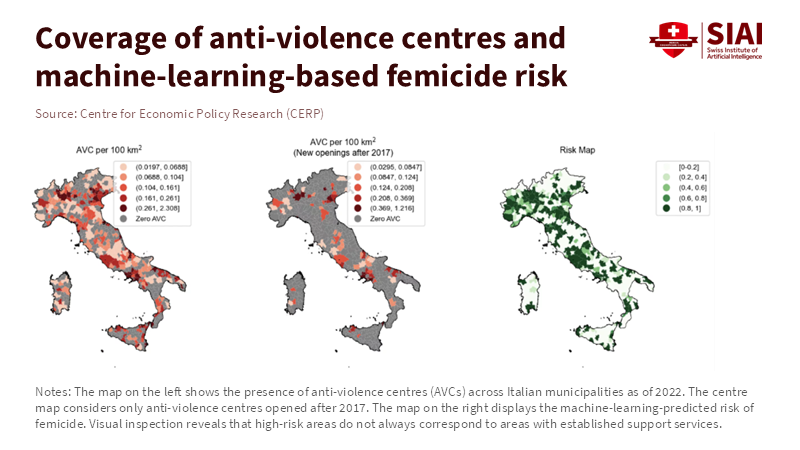

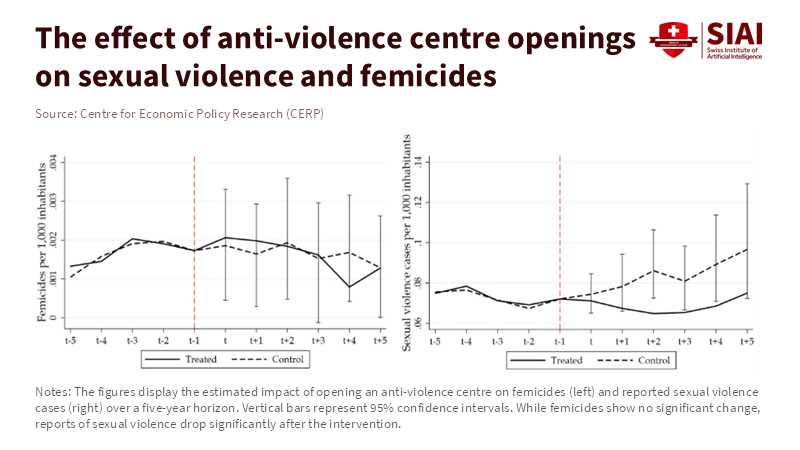

According to a report from Euronews, in the EU, women are nearly twice as likely as men to be killed by a partner or family member, underscoring that most femicides occur within families and often at home. This pattern may help explain why higher rates are sometimes found in rural areas and small towns. According to a report from the United Nations Regional Information Centre for Western Europe, the home is often the most dangerous place for women and girls, with 60 percent of female deaths occurring within their own homes. While smaller populations, fewer services, and stricter social norms in certain areas can make victims feel trapped, it is clear that focusing only on geography does not capture the full reality. When we compare services, how close houses are to each other, and where anti-violence centers are located with femicide rates, we see a more complicated picture. According to UN Women, cities can pose greater risks due to larger populations and a higher potential for marginalization, but they also often offer specialized services and support networks that can help protect vulnerable individuals. If we compare rates without asking who lives where—their legal status, family situation, and access to services—we might mistakenly think that the place itself is the cause, rather than the social problems in that place. Studies show that femicides committed by family members go down when there are more resources for victims and better prosecution. However, these resources don't reach everyone equally, depending on where they live and what group they belong to.

Comparing different areas without accounting for population mix—such as the number of migrants or non-native communities—treats cities as if they were the same everywhere. This causes two problems. First, it makes our statistics wrong. For example, the effect of living in a rural area might seem stronger than it really is because it's picking up on problems related to the people who live there. Second, it creates blind spots in our policies. Programs designed for rural areas with few services won't solve the problems in crowded, segregated urban areas. Good policy starts with breaking things down into smaller parts. We need models that separate native-born and migrant populations, account for unstable housing, and indicate where specialized services are located. When we add these factors, the effect of place often becomes smaller or even reverses, suggesting that the original rural effect was just a stand-in for other social issues we weren't measuring.

Why adding a migration/compositional variable matters (and how to do it)

Asking whether migration or cultural background plays a role in femicide isn't about blaming anyone; it's about being accurate. Studies show that migrants and displaced people are more likely to be victims because they have weaker support systems, language barriers, and uncertain legal status. While it is evident that migrants—especially those who are forcibly displaced, undocumented, or subject to multiple forms of discrimination—face a higher risk of experiencing violence, it remains unclear if they are the main group responsible for such acts on a large scale. A more pressing question is whether local femicide rates are influenced by factors such as the number of migrants, levels of poverty, and the availability of support services, and how these elements interact with anti-violence policies. According to the European Institute for Gender Equality, migrants are particularly vulnerable to various forms of violence. To answer that, researchers need to collect two kinds of data: (1) the relationship between the victim and offender, and the offender's origin/nationality, if recorded, and (2) information about the number of migrants, housing density, and service accessibility in specific areas. Current international reports and regional monitoring highlight hotspots in the Balkans and Eastern Europe, but also note that information about where perpetrators come from is missing, and community-level factors are often not counted.

One way to approach this is by using multilevel modeling, which groups incidents within cities and considers how policies affect different groups. Important factors to include are the number of migrants in an area (by country of birth and year), measures of economic hardship (unemployment, welfare use), the presence and resources of anti-violence centers, and the number of people with temporary legal status. If we don't have direct data on where perpetrators come from, we can use other methods to estimate it. We can also model the maximum error a missing factor could introduce to make our results clearer. These aren't complicated statistical tricks; they're just responsible ways of saying we don't know without causing people to misunderstand.

Policy consequences: Better data, smarter targeting, and avoiding stigmatization

If leaving out factors like population mix biases our models, our policies might be misdirected. According to a 2023 report from the European Institute for Gender Equality, focusing support only on rural shelters without addressing the needs of migrants and residents in urban hotspots risks leaving out vulnerable groups, particularly those facing language or legal barriers. The report also suggests that effective responses to femicide in urban areas often require combining investments in anti-violence centers with outreach and integration services. This suggests a balanced approach: improving legal protections and prosecutions for everyone, along with tailored outreach involving interpreters, cultural mediators, and trusted organizations. Evidence from the Western Balkans shows that femicide rates stay high even with legal reforms if service networks are weak.

We must avoid stigma. Disaggregating data by migration background could fuel blame. We should clarify the model's limits and design programs that support victims, not treat them as criminals. Practical steps include anonymous reporting, keeping immigration enforcement separate from victim support, and investing in culturally informed services. Good programs use data to allocate resources, not make moral judgments.

From better models to better policy

We started with a number that made us rethink things: tens of thousands of gender-related killings per year are only now being seen because we're counting better. The lesson for European policy is the same. When models ignore important factors like migration mix, unstable housing, and access to services, we might misunderstand the causes of femicide and misplace resources. The right response is to do three things. First, improve data collection to record victim–offender relationships and population information while protecting privacy. Second, re-estimate the impact of policies using detailed models and clear estimates of potential errors so that researchers and policymakers can see how much a missing factor might matter. Third, combine targeted programs with safeguards that prevent stigmatization and ensure the goal is protection, not punishment. In practice, this means having more mobile outreach teams in urban areas, help lines in different languages, legal protection that isn't tied to immigration enforcement, and stronger rural services where isolation is a major risk. This approach will improve our reach and reduce misunderstandings in public discussions. The problem of femicide is less about finding a single cause and more about avoiding simple explanations. If we improve our data and methods, we'll improve our policies—and save lives.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

AP. (2024). An average of 140 women and girls were killed by a partner or relative per day in 2023, the UN says. AP News.

European Parliament Research Service. (2025). Violence against women in the EU: State of play in 2025. European Parliament Briefing.

Euronews. (2024, May 3). Women are being murdered in the Western Balkans, and it is time to take action. Euronews.

OSCE. (2024/2025). Trends in addressing femicide in the OSCE region. Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe report.

UNODC / UN Women. (2024). Femicide in 2023—Global estimates of intimate-partner and family-member femicides. United Nations analytical brief.

WAVE Network. (2023). WAVE Country Report 2023: Femicide and services across Europe. WAVE—Network to End Violence Against Women.

Comment