Rebuilding Ukraine: Why the Korea 1953 Template is Useful — but Not Enough

Input

Modified

Ukraine cannot rely on the 1990s transition model without rebuilding core infrastructure The Korea 1953 case shows why catalytic capital must target hard assets first A phased Ukraine reconstruction strategy is key to unlocking private investment and EU integration

The price tag for rebuilding Ukraine after the war is huge, estimated at around $524 billion over the next 10 years. That's a number that should grab the attention of anyone in charge. But it's important to remember that this number isn't just a blank check; it's a way of understanding the problems that need to be solved. Right now, there are two main ideas for how to approach this: should we copy what happened in Eastern Europe after the fall of communism in the 1990s, or should we treat Ukraine like a country devastated by war, like Korea after the Korean War? Both ideas have their strengths and weaknesses. According to a study by Winkler and colleagues, it is important to recognize the progress Ukraine has already made in building institutions, while also addressing the urgent need to rebuild the country's infrastructure quickly and on a large scale, using reliable data sources to guide these efforts. This writing argues for combining these methods. We should use that $524 billion figure as a guide, focusing on attracting investment that gets things moving, ensuring projects are carried out responsibly, and connecting Ukraine to European markets.

Why the Post-1991 Plan Doesn't Quite Fit

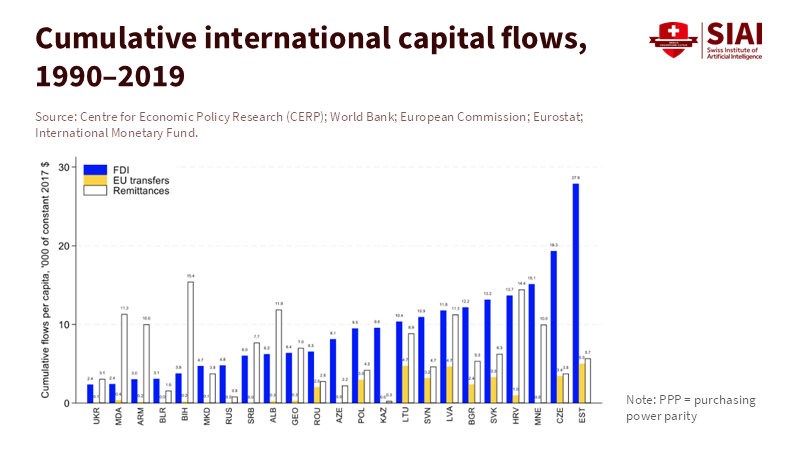

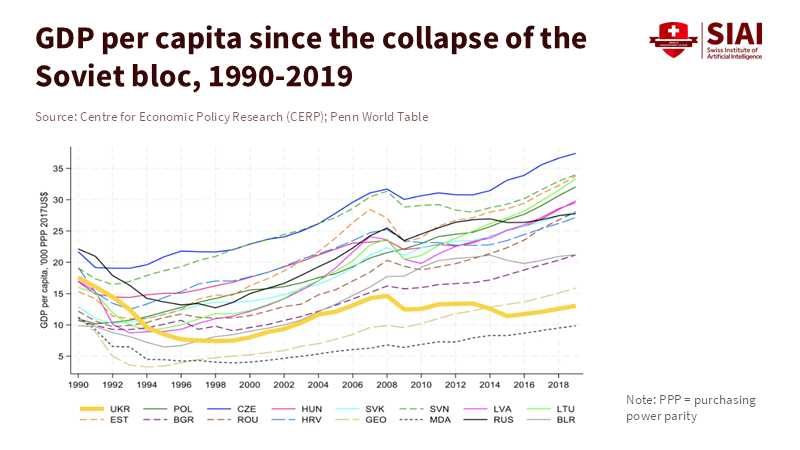

The changes in Eastern Europe after 1991 were more about establishing new systems than rebuilding physical structures. When the Soviet Union fell apart, those countries already had roads, factories, power grids, and buildings. What they didn't have were things like market rules, reliable property rights, and modern tax systems. So, foreign aid and local leaders focused on building those systems, such as courts, corporate laws, antitrust regulations, and taxes. These changes were important because they enabled the use of existing infrastructure and encouraged private companies to invest in operations rather than rebuild everything from scratch. Back then, the biggest problem was governance, not the physical state of things. That's why the focus in the 1990s was on rapidly changing regulations and the sale of state-owned businesses. But applying that same idea to Ukraine now, after the war, won't work as well. Now, the problems are about both things, like steel and wires, and laws and rules.

So, fixing institutions is still important, but it's not enough when so much physical damage has been done. Ukraine has been adopting European policies and practices for years, which should make it easier to set up good governance after the war. But the stress of the war, the displacement of people, and damage to important community buildings have made it harder for local agencies to do their jobs. If a lot of money is poured into shaky institutions too quickly, there's a high risk of corruption and misuse. Those providing aid need to address these limitations by developing project plans, training people to manage contracts, and bringing in independent project managers. We shouldn't measure success by how fast the money is spent, but by how well the rebuilding restores businesses and creates jobs. Spending money quickly without a plan will just lead to useless projects, not growth.

A good rebuilding plan for Ukraine needs to start with a clear order of priorities. The first thing should be projects that restore movement and connections: fixing main power lines, important transportation routes connecting ports to industrial areas, and local water and sewage systems. These projects will get the economy moving again. At the same time, those providing aid should invest in improving the ability of institutions to handle projects – training in how to manage purchases, systems to prevent fraud, and independent oversight. Finally, it's important to fund social support and temporary housing to stabilize the population during the rebuilding.

Donors can make a bigger difference by using contracts that allow reconstruction to continue even if security conditions change. These kinds of contracts, along with standardized bidding documents and plans for unexpected problems, reduce the costs of starting and stopping projects and keep contractors working. Small, quick-response teams that can fix parts of the power grid or reopen bridges can create early successes and keep people employed locally.

Lessons from Korea After 1953

Korea after the Korean War is a good comparison because it also involved significant physical destruction followed by rapid industrial development. A large amount of equipment and infrastructure was destroyed, and there were gaps in skills and knowledge. Aid from other countries in the form of grants, low-interest loans, and expert support helped rebuild ports, roads, and basic factories. What was important was that this aid was used within a system that focused on industrial development – directing loans, promoting exports, and investing in important industries. Japan's agreement in 1965 to provide about $300 million in grants and low-interest loans was significant because it demonstrated political cooperation and opened the door to management and diplomacy. The important thing to remember is that aid is more helpful when it's part of a plan that supports the market.

But there are also differences between Korea then and Ukraine now. During the Cold War, Korea's location made it a focus for aid and political attention. Also, the global market at the time made it easier for Korean exports to find buyers in developed countries. According to Aju Press, the South Korean government is currently demonstrating effective coordination of finance, technology, and industrial policy by launching a 50 trillion won fund to support key high-tech industries such as semiconductors, biotechnology, and artificial intelligence. Ukraine, however, faces a different set of circumstances. It's located next to the EU single market, which means there's a lot of demand nearby, but also strict rules and competition. This reduces the opportunity for special industrial policies, but it makes it more beneficial to align reconstruction with European standards – product standards, certifications, and infrastructure that connects Ukrainian production to European supply chains. Aligning reconstruction with EU rules raises the standards for industrial improvement in Ukraine. That alignment is an advantage if Kyiv and donors take a step-by-step approach: start with transportation routes and products that require the least regulatory change, and gradually improve standards as capabilities increase.

Timing is also important. Korea's postwar rebuilding was driven by rapid growth in sectors such as manufacturing and supported by political priorities during the Cold War. In contrast, current reconstruction efforts are unfolding in a more uncertain global environment. Aid money is being discussed through many channels – public promises, private investment offers, and new ideas for using frozen Russian assets or their income. Policy ideas circulating among officials sometimes add up potential funding to around $800 billion, when private investment pledges, donor commitments, and the reuse of frozen assets are combined. These totals help us think about the scale of what's possible, but they're not immediately available cash. Frozen assets face legal and political obstacles, and converting them into ongoing funding will be slow and contingent. Policymakers need to treat these amounts as potential upper limits and create a financial system that links payments to confirmed progress and legal clarity.

Policy Choices That Will Determine the Results

Any credible rebuilding plan for Ukraine needs to combine public funding to get things moving with ways to attract private investment. First, donor grants should focus on public resources and investments that involve risk – ports, major power lines, highways – that private companies can't provide at the scale or speed needed. Second, low-interest loans and guarantees should target private projects that are likely to succeed: rebuilding factories, housing with mortgage support, and credit lines for small businesses. Third, insurance and other ways to cover initial losses are important for reducing the political risk that keeps commercial investment away. Without these three things, large amounts of money will sit unused or be used for activities that don't help the economy. Donor channels already being discussed at the EU level can help combine resources and provide reliable funding for early-stage projects.

The design of these programs is important because it affects incentives. Guarantees without conditions create risk; grants without purchasing controls create waste. A well-designed system involving multiple donors should include rules for fair purchasing, independent technical evaluations, civil-society oversight, and public dashboards showing project progress and payments. This kind of system makes it more difficult to misuse funds and rewards good performance. It also reduces costs for private lenders, as consistent standards make it easier to assess projects. Requiring third-party technical audits and publishing the results reduces uncertainty. Civil-society partners should receive funding specifically for monitoring, and there must be strong protection for those who report wrongdoing. These steps are essential in environments where large amounts of money are being spent on rebuilding.

In practice, donors should commit to releasing funds in stages based on verified progress. Early payments should finance emergency repairs and social support. Middle payments should fund the main infrastructure and legal changes that resolve property and land claims. Later payments should support commercial projects and guarantees that attract private investment. This order follows the approach that worked for Korea, but adapts it to European integration and the fact that modern supply chains require regulatory alignment as much as physical infrastructure. Resolving land and property claims early encourages investors and avoids expensive lawsuits later. According to the Council of the EU, recent G7 loan commitments and financial guarantees to Ukraine have been structured with staged releases linked to progress. The Council recently approved a financial assistance package that includes up to €35 billion in loans and a mechanism supporting Ukraine’s repayment of loans from the EU and G7 partners, providing greater certainty for reconstruction efforts.

Political Factors and Regional Integration

Politics will play a role in where and how rebuilding money is spent. Local leaders will push for projects in their areas, and national companies will seek special treatment. To prevent corruption, the rebuilding system needs to make allocation choices transparent and open to challenge. Independent monitoring, open data platforms, and conditional payments create financial and reputational risks for those who misuse funds. Donors should also use incentives: co-financing that rewards cities and regions that meet purchasing and transparency standards, and matching grants that encourage investment with local authorities who have credible plans. National ministries can handle strategic projects, while regional administrations can be rewarded for meeting transparency standards. This balance prevents central control while ensuring coordination for large systems that cross regional boundaries.

Regionally, donor coordination should prioritize projects with clear cross-border benefits and that connect Ukraine economically with Europe. Power connections, transportation routes, and standardized digital infrastructure create immediate market access and commercial connections that support investment. If national governments insist on using domestic contractors, pooled purchasing and transparent co-financing can direct work toward competitive bids rather than political favors. If member states can offer market access in exchange for compliance with European standards, those conditions should be clear and supportive. The goal is to make reconstruction a path into European supply chains, not a separate economy.

Remember, that $524 billion number is a map, not a blank check. Ukraine has knowledge and experience from the post-1991 era that reduces some reform costs, but the scale and location of wartime destruction require careful and strategic investment. Combine Korea's lesson of providing seed money for physical infrastructure with a European integration strategy that links reconstruction to market standards, cross-border transportation, and transparent practices. Donors need to resist pressure to spend quickly and unrestrictedly and insist on phased, verified payments and pooled implementation systems. Guarantees should be used to attract private investment only after governance and legal risks have been addressed. This focused combination turns reconstruction funding into a reliable engine for jobs and trade. The reconstruction period is not just about money; it's a political test for Ukraine and for European solidarity. If we deliver results, the outcome will be sustainable growth and closer ties to Europe.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Caliber.az. (2026). EU, US eye $800 billion prosperity plan to rebuild postwar Ukraine.

CEPR / VoxEU. Gorodnichenko, Y. & Obstfeld, M. (2026, January 26). You only live twice: A growth strategy for Ukraine.

European Commission. (2024). The Ukraine Facility: EU support for recovery, reconstruction and modernisation (2024–2027). European Commission reports.

Reuters. (2024, March 20). EU to give Ukraine 3 bln euros of profits per year from Russia assets.

Reuters. (2024, October 25). G7 leaders agree to deliver $50 bln in loans to Ukraine as soon as December.

Treaties UN. (1965). Treaty on Basic Relations between Japan and the Republic of Korea (Agreement on property, claims and economic cooperation).

World Bank. (2025, February 25). Updated Ukraine recovery and reconstruction needs assessment (RDNA4): $524 billion over the next decade.

Comment