Hidden Decoupling: Why U.S. Imports Look Diversified but Are Not — Series A

Input

Modified

U.S. import diversification masks continued supply chain concentration Much of the shift reflects rerouting, not real relocation True resilience requires tracking value chains, not labels

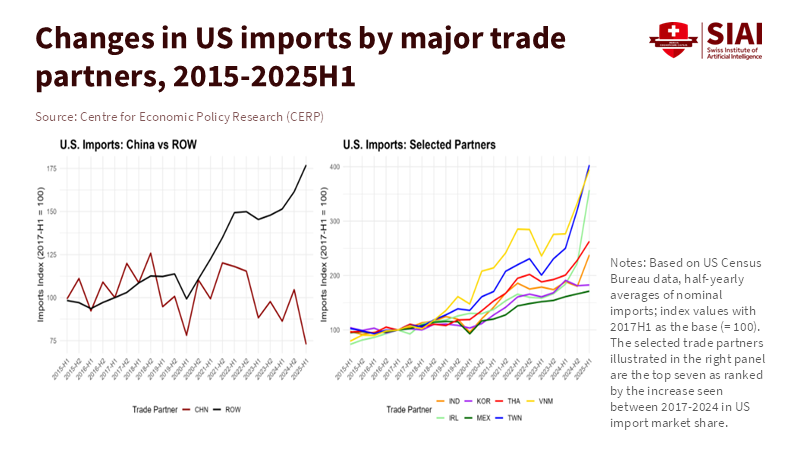

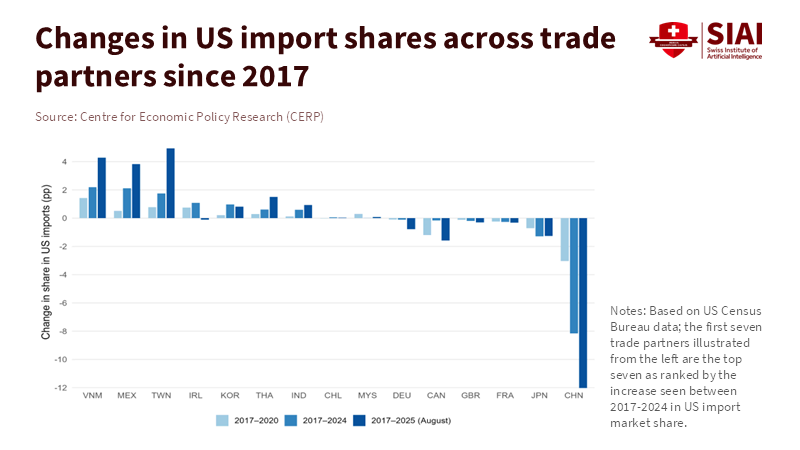

U.S. trade data shows a seemingly positive change: China's portion of goods imported to the U.S. decreased from about 21.6% in 2018 to roughly 13–14% by the mid-2020s. At first glance, this appears to be a win for diversifying supply chains. The reality, though, is more complex. A significant portion of the imports that seemingly shifted away from China didn't come from new, fully independent sources. Instead, these goods were often rerouted, relabeled, and only slightly modified, while still heavily dependent on Chinese components or final assembly. This creates the appearance of diversification, but it's really built on transshipment and a fragmented value chain, not a true reduction of risk. This difference is critical. Policymakers, businesses, and educators who base their strategies on simple import numbers are likely to underestimate how vulnerable our systems are. When disruptions occur – such as sudden tariff increases, widespread disease, or port shutdowns – the safety net they expect might not be there. The key factor to watch is supply chain concentration. The country listed on shipping documents is no longer a dependable guide to where the actual risks lie.

Rethinking Diversification: It's About Content, Not Just Country

Instead of focusing solely on country-level import percentages, we need to examine the composition of those imports. Just because China's direct market share has decreased doesn't mean we've achieved real diversification. The alternative suppliers might simply be intermediaries. For we examine: Increased exports from countries like Vietnam, Malaysia, or Thailand could mask the fact that the core processes – the components, the tools, and even the final assembly – are still largely tied to China.

The mistake is associating supply-country diversification with lowered risk. What truly matters is not the declared origin of the shipping container, but where the most critical inputs were made and where the most labor-intensive processes took place. Studies that consider value added, company ownership, and shifts in the flow of materials between countries show that many new suppliers are closely connected to Chinese production networks. In effect, the U.S. hasn't really decoupled from China; it has simply rerouted its supply lines.

How Rerouting Works: Two Key Approaches

Looking at the details, we can see two distinct patterns. First, there's genuine relocation. Companies establish factories in other countries, source materials from local suppliers, and make real changes to their supply base. Second, there's rerouting – goods made in China are sent to a nearby country for minor adjustments or repackaging, then exported with a new country of origin label.

Research analyzing customs records, company ownership, and sudden increases in exports to third countries suggests that rerouting accounts for a significant portion of the apparent move away from China since 2018. These analyses often identify unusual patterns, such as rapid increases in exports to transit countries coupled with decreases in direct exports from China to the U.S., ownership connections (the same companies having operations in both China and the transit country), and unchanging patterns in product complexity or material inputs. These trends, evident in recent research papers and policy reports, suggest that headline diversification does a poor job of reflecting continued risk concentration in supply chains linked to China.

The Problem with Transshipment: Rules of Origin Are No Longer Enough

Transshipment is the tactic that turns real decoupling into a superficial change. Customs reforms and the threat of tariffs motivate companies to send goods through Southeast Asia, Mexico, or other intermediate locations. However, when the work performed in the transit country adds little to the product's overall value, the declared origin becomes questionable. Recent studies document clear spikes in Chinese exports to Vietnam and nearby economies just before or at the same time as decreases in direct shipments from China to the U.S. This suggests that firms are trying to avoid tariffs and maintain access to markets.

The result is that a U.S. importer might list Vietnam as the origin on shipping documents, even if most of the value was created in China. This creates a double illusion: import statistics and those who rely on them see diversification, while those who examine systemic risk see continued concentration.

Current legal standards for judging substantial transformation, along with the paperwork required to enforce rules of origin, often fail to prevent this kind of avoidance. While some transit countries are developing their own industries and building local capabilities, others mainly serve as assembly or packaging points, which are easily used for transshipment. The capacity to enforce the rules also differs from place to place. In areas where customs and auditing systems are underfunded or stretched thin, the incentive to transship increases.

This poses a difficult choice for policymakers: they can tighten the rules of origin, potentially stifling genuine regional investment, or accept that their diversification numbers are inaccurate. The government's response is often a mix of both: selective penalties for suspected transshipment, targeted checks of origin, and negotiated agreements between countries aimed at distinguishing between genuine supply chain shifts and simple relabeling. So far, the result has been fragmentation. Supply chains are becoming less global and more regional, with hidden pathways that concentrate risk in new – and sometimes unseen – places.

Implications for Education, Business, and Policy

The shift from apparent diversification to hidden concentration has major implications for how we teach, plan, and make policy.

Education: A curriculum that defines resilience solely in terms of the number of suppliers and their locations will be ineffective if it doesn't account for the actual content of the supply chain. We need to teach students about procurement and risk assessment, focusing on supplier ownership, the origin of materials, and the proportion of critical components made in a single location. Business schools should emphasize analyzing value added across borders instead of simply relying on overall trade figures. STEM and vocational training programs should focus on the real centers of production. If activities like robotics or semiconductor packaging remain concentrated in particular factories, even if those factories are in different countries, then workforce training and equipment strategies should reflect this.

Administration: Administrators need to revise their contingency plans. Universities that depend on a diverse set of vendors for equipment, medical supplies, or food services might still be at risk if many of those vendors rely on the same Chinese suppliers. Purchasing departments should require suppliers to disclose the origin of critical components and conduct risk assessments to uncover single points of failure in supply chains.

Policy: Trade negotiators and regulators need better tools for measuring concentration based on supply chain content. This requires using input-output tables, detailed customs data, and corporate ownership records to map out real dependencies. The focus should extend beyond tariffs, which can lead to rerouting. Border inspections can catch some instances of avoidance, but can also slow down legitimate relocation of supply chains. Smart policy should combine technical audits, targeted industrial initiatives to build real capabilities in partner countries, and create incentives for firms to diversify where critical production happens – not just the final packaging.

Addressing Concerns: The Evidence Speaks for Itself

Some might argue that rerouting is being exaggerated, that policies have effectively shifted supply away from China, and that increased exports from countries like Vietnam and Mexico represent genuine diversification. We need to address these claims with careful analysis of the data. Counting exports as a percentage of U.S. imports is too simple. A more accurate view compares the makeup and value of those exports. If the products exported by Vietnam display characteristics and prices similar to those of previous exports from China, it suggests rerouting rather than true substitution.

Data about company ownership and customs records also reveal that many of the new exporters are foreign-owned or Chinese-owned firms with factories in other countries, directly linking the new supply to China's industrial base. Studies analyzing inputs using input-output tables show that a large share of the value often originates in China, even if the final product is labeled differently. These aren't just isolated cases; many research papers and policy reports have reached similar findings using data from recent years. This collective evidence supports the argument that what appears to be diversification often hides continued dependence on China.

Further, real relocation is expensive. Companies that move actual production must invest in facilities, local suppliers, and workforce training. Often, they haven't made these large investments. Where tariffs and international politics make the investment worthwhile, we see it occur. Where they don't, we see cheaper solutions: repackaging, minimal modifications, or changing a single component to meet the rules of origin. This is why some diversification is lasting, while some is just for show. To encourage deeper, more lasting relocation, we need incentives that offset the real costs, such as subsidies, workforce support, or infrastructure improvements in partner countries. Otherwise, the market will settle into a fragile and fragmented state.

A Better Approach to Policy and Education

A practical policy plan will have three main components:

1. Measurement: Develop routine, public dashboards that show concentration metrics based on supply chain content. These should combine data from customs, company ownership records, and input-output analyses to reveal not only where imports are registered but also where critical inputs are produced.

2. Targeted Resilience: Shift from broad tariffs to focused partnerships that incentivize real local production for a defined set of critical goods. This means clear, time-limited investment rules that require minimum levels of local value added and supplier development plans.

3. Enforcement and Cooperation: Strengthen the ability to verify origin in transit countries and create fast-track audit partnerships so that suspicious rerouting can be addressed quickly without disrupting legitimate trade. These actions reduce the incentive for superficial relabeling and direct investment toward building real capabilities.

These policy changes also mean changes in education. Risk analysis courses need to teach students to look beyond what's written on shipping documents. Procurement classes must train officers to request value chain maps and evaluate suppliers based on component concentration. Programs focused on public policy must learn to create incentives that focus on actual change, not just relocation.

A campus that adopts these lessons will not only improve the resilience of its own procurement practices but also prepare the next generation of leaders to build supply chains that are truly diversified, rather than just superficially so.

Act on What Matters

If the decrease in China's share of U.S. imports feels like progress, it’s mostly progress in appearances, not in substance. The statistic that started this discussion is still useful, but we can't treat it as the whole story. Supply chain concentration now exists through hidden pathways: foreign factories owned by Chinese companies, centers for light processing that relabel goods' origins, and supply chains that remain closely interconnected despite the new country names on the paperwork.

The solution is not a single tariff or trade vote. It's measurement, targeted industrial policy, and better procurement practices grounded in the reality of where value is created. For educators, administrators, and policymakers, the task is straightforward: teach and measure the real centers of production, create incentives that require genuine local change, and build enforcement partnerships that make superficial labeling unprofitable. By doing these things, diversification will mean less illusion and more resilience.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Brookings Institution. 2025. “China’s transshipment of goods to the US.” Brookings.

CITP (Center for International Trade and Policy). 2025. Iyoha, E. “Trade Rerouting during the US–China Trade War.” CITP Working Paper.

China Briefing. 2025. “How US Tariffs on Southeast Asia Could Impact China’s Transshipments.” China-Briefing.

Liberty Street Economics (New York Fed). 2025. “U.S. imports from China have fallen by less than U.S. data indicate.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

MERICS. 2024. “Mapping import dependencies in EU and US trade with China.” MERICS Report.

ResearchGate / UCSD. 2025. “The China Wash: Identifying Tariff Evasion via Transshipment.” UCSD working paper.

Trading Economics / UN COMTRADE. 2024–2025. Vietnam exports to United States (data summary).

UNCTAD. 2024. Koloskova et al. “Insights from United States of America - China trade patterns.” UNCTAD Working Paper.

United States International Trade Commission (USITC). 2022–2024. “Economic impact of Section 232 and 301 tariffs on U.S. industries.” USITC Publication.

U.S. Census Bureau. 2024–2025. “Trade in Goods with China” monthly data.

Comment