The AI Labor Divide: Who Wins, Who Survives, and Who Falls Away

Published

Modified

AI is creating a sharp labor divide between capital owners, stable workers, and those being pushed out Education policy must adapt to this new AI labor divide or risk permanent inequality Public finance and schooling must evolve together to prevent economic exclusion

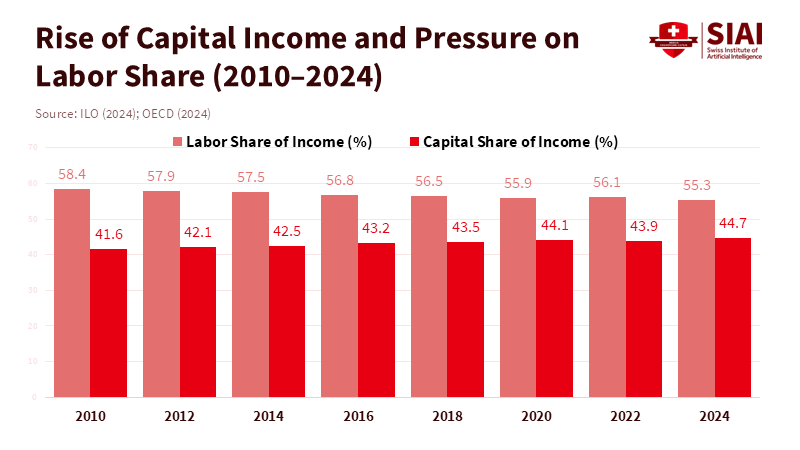

Artificial intelligence is not just changing tasks; it is altering who earns a living at scale. The clearest early pattern — and the one that should steer policy now — is an emerging AI labor divide: a thin stratum of owners and integrators captures most gains, a broad middle manages to keep pace, and a shrinking tail loses both jobs and wage share. That pattern already maps to capital income rising while labor’s share stalls or falls. This is not a far scenario. Recent cross-country and policy analyses show the same tilt: corporate profits and returns to capital are growing faster than wages, automation is reallocating work inside firms rather than creating broad new demand for labor, and public-finance models now treat taxing AI-driven capital as a core fiscal question. If teachers and lawmakers treat AI as a productivity puzzle rather than a redistribution problem, we will miss the moment to shape schools, tax systems, and safety nets to preserve social and civic functioning.

Understanding the AI Job Divide: The Rich, the Okay, and the Poor

The first thing to understand is that the way our economy is set up is dividing people into three groups that are likely to stick around for a while. At the top are the have-lots—the people who own the best AI technology, big internet platforms, and the investment funds that pay for automation. They make a lot of money because AI replaces workers, making it easier to grow their businesses. Below them are the haves—workers and small businesses who still do work that's valuable enough to keep their pay steady, or whose services are made better by AI, which helps them stay in business. At the bottom are the have-nots—workers whose jobs are easy to automate or who work in areas where there's less and less demand. These people are making less and less money.

It's important to understand this three-part picture because it clarifies where we need to step in. It's not only about retraining people. It's also about changing our tax system, creating jobs, and establishing support systems to prevent money from continuing to flow to those who already have it. We're starting to see evidence that this is really happening. A report from Axios notes that although organizations invested between $30 billion and $40 billion in generative AI, 95% saw no return on their investments, highlighting that AI-generated wealth is largely concentrated among a small number of successful companies. Financial analysis has documented similar trends in the growth of corporate profits and the decline in workers' incomes over the same period.

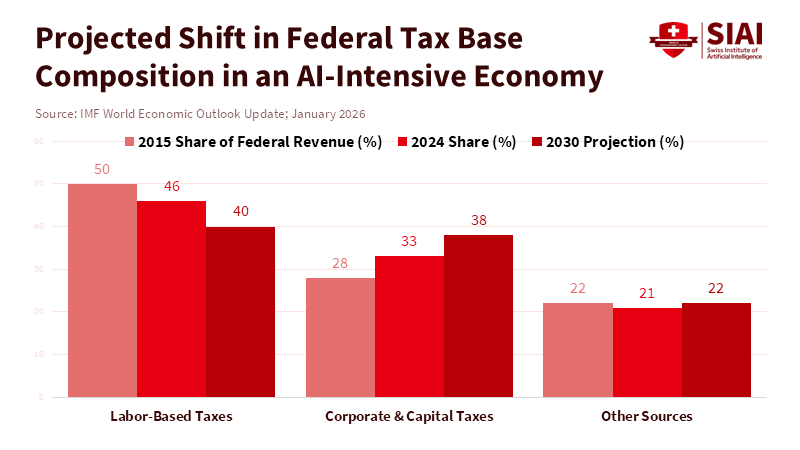

On the government policy side, new studies examine how government finance might function in a world with AI. They're considering treating AI systems and computing power as new resources we can tax and suggesting ways to get some of the money flowing to the people who own AI. These aren't merely opinions; they reflect real changes in how income is distributed and how companies generate revenue.

In numerical terms, many data collections indicate that the share of national income going to workers has been under pressure for years. And now AI is intensifying that pressure. International organizations report that workers' incomes have not returned to pre-pandemic levels, and companies' profits are increasing even when economic growth is modest. The exact numbers vary by country and measurement, but the trend is clear: AI is amplifying a trend that began in the late 20th century. This is important for schools to understand because the nature and extent of job losses will determine what schools need to teach and the types of support programs required.

What This Means for Schools, Credentials, and What We Teach

If this divide created by AI worsens, schools will face two challenges. First, they need to prevent people who are pushed into the have-nots category from being permanently stuck there. Second, they need to change how we issue credentials and create career paths so the haves can keep making money without making it too hard for others to earn the credentials they need. This means we need to stop thinking only about future skills and start thinking about a mix of skills, ways to redistribute money, and changes to our institutions.

Skills are still important. Skills such as solving complex problems, understanding digital technology, and adapting to different situations will help many workers remain useful alongside AI. But skills alone aren't going to solve the main money and distribution problem. If most of the money from increased productivity goes to the people who own investments, then the economy can grow while most people's standard of living stays the same.

What this means for what we teach is that we should include four things. First, we need to connect technical training to the real world of economics. We need to teach people how AI makes money and who gets that money so that they understand how internet platforms and business models work, not just how to write code. Second, we need to make credentials that are modular and stackable the norm. This means creating shorter, validated paths aligned with employers' needs, reducing the time and cost of re-entering the job market. Third, we need to invest in teaching methods that combine human decision-making, oversight, and ethics. These are areas where humans are still valuable in supervising and correcting what AI does. Fourth, we need to expand career transition programs that are connected to community colleges and regional groups. These programs should connect displaced workers with growing industries in their local area rather than focusing solely on the national job market.

There's also a fairness issue here. Not all areas have the same ability to help displaced workers find new jobs. Some areas where the have-nots are concentrated might keep most of the opportunities for themselves. This means the federal government and charitable organizations need to provide more support for regional retraining centers and make it easier to transfer credentials between states. It also means we need to ensure that education funding is flexible, with measures such as tax credits for training, income-based microloans for short programs, and public investment in programs that target people most likely to be in the have-not category. These are specific steps we can take to reduce the social impact of the AI job divide while still encouraging innovation.

Rethinking Taxes, Government Finances, and Institutions to Support Education

We can't separate education from the financial arrangements that pay for it. If AI concentrates capital in investment rather than wages, then traditional payroll taxes and income taxes on labor will become weaker as stable sources of revenue. That puts funding for public schools, higher education subsidies, and the training programs essential to helping people transition at risk. That's why the new financial framework includes measures such as taxing computing power or the revenue generated by AI systems to capture some of the additional revenue.

There are specific policy ideas that align with education goals and fiscal realities. One is to create a dedicated AI dividend or investment fund that uses a small portion of AI profits to support a national training fund for community colleges and apprenticeship programs. Another is to change employer incentives so that companies that benefit from automation contribute to local retraining efforts through levies, pooled wage funds, or tax credits tied to successful retraining outcomes. A third is to view public investments in lifelong learning as infrastructure, like roads or broadband. Learning systems need steady, predictable funding that can survive economic ups and downs.

Some people will say that these steps may discourage innovation or create heavy burdens for companies. Those are reasonable concerns. But policy can be designed to be fair and neutral. A small levy on computing power or a tax on profits from AI systems can be adjusted to protect research and development while still generating money for retraining and social safety nets. It's important for education leaders to ensure that any new revenue streams are used specifically for training, credential portability, and transition services, rather than being mixed into general spending where they can be easily diverted.

Responding to Concerns: Faith In Productivity, Faith in Retraining, and Political Practicality

Some people are optimistic and will say that AI will create new jobs and that technology has always led to net gains for workers over time. That's possible, but it's important to look at the details. Past technologies often reallocated labor across industries and locations. AI replaces cognitive tasks and concentrates money through digital platforms and intellectual property. Recent studies suggest that the immediate impact of AI has been to reallocate tasks within companies and to create gains for capital owners rather than to create many new jobs across the economy. So, it's risky to rely on historical comparisons without making structural policy changes.

Another argument is that retraining can address most displacement. Retraining is necessary but not enough. It helps people who can get access to quality programs and who are in areas where there's demand for new skills. But for many workers who are geographically isolated, older, or have caregiving responsibilities, retraining without income support and job placement services is not a complete solution. This is where coordinated policy is important. We need to combine training with wage protection, portable benefits, and information on employers' needs so that retraining leads to real jobs, not just inflated credentials. Finally, political practicality is a real barrier. People with a lot of money have incentives to slow down or shape reforms that would reduce their gains. That's why education leaders and administrators need to be proactive. Schools and colleges can form alliances with labor groups, regional businesses, and civic organizations to create durable local systems that deliver retraining at scale. These alliances change the political situation. When local economies see clear paths from public training to business hiring, the argument for shared investment becomes stronger. The alternative is a collection of large but ineffective national plans that never reach the workers who are most at risk.

Base Education Policy on Reality, Not Just Optimism

We commenced with a simple idea: the AI job divide is forming now, and it's dividing the economy into those who have a lot, those who have enough, and those who don't have enough. That classification is important because it indicates where policy should focus. It's not only about teaching people new skills, but also about remaking the institutions that fund learning, support transitions, and capture some of the money AI creates for public goods. For educators, this means changing curricula to focus on economic context, modular credentials, and human-monitoring skills. For decision-makers, it means modernizing tax systems and creating durable local retraining systems. For administrators, this means forming partnerships across sectors and ensuring that training programs deliver measurable hiring outcomes.

If we don't act, we're likely to end up with a stable economy with a growing GDP but weakened social foundations. There will be fewer taxpayers funding schools, more families relying on weak private retraining markets, and sharp regional divides where opportunities are concentrated around AI hubs. The practical approach is to treat education and government finance as two parts of the same response. Let's redirect a portion of AI profits toward lifelong learning, make credentials portable across areas, and design fair, modest taxes on AI that fund training and transition support. These steps are feasible, politically defensible, and morally urgent. They won't stop disruption, but they can make sure that disruption doesn't turn into permanent exclusion.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Axios (2026) AI rush creates rarified class of “Have-Lots”. 12 January.

Brookings Institution (2026a) Future tax policy: A public finance framework for the age of AI. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Brookings Institution (2026b) Public finance in the age of artificial intelligence: A primer. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Economy.ac (2026) Corporate profit concentration and labor share decline in the AI era. Economy.ac Research Brief, February.

International Labour Organization (2024) World Employment and Social Outlook: Trends 2024. Geneva: ILO.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2024) The impact of artificial intelligence on productivity, distribution and growth. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Comment