Stable Savings, not Speculative Savings: Why the Crypto Affordability Myth won't Fix U.S. Household Strain

Input

Modified

Speculation cannot fix structural affordability Stablecoins may look stable but can shift systemic risk Real reform requires stronger incomes and safer credit systems

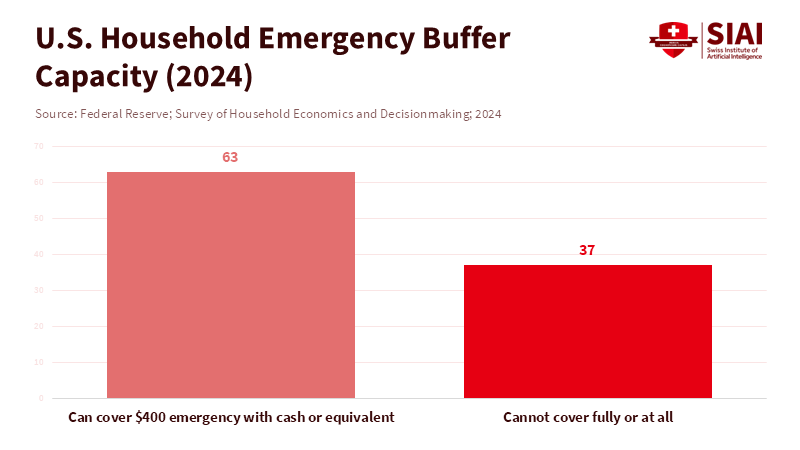

In 2024, a study found that about 63% of adults in the United States had enough savings or available cash to handle a $400 emergency. However, that also means that a worrisome 37%—more than one in every three people—would struggle to cover such an unexpected expense. Even more worrying, 13% said they wouldn't be able to pay it off at all. This paints a clear financial picture for many families and shows the real problem: many people don't need fancy new ways to manage their money; they need more reliable income and some savings to fall back on. Despite this, some people are talking about crypto, especially stablecoins (which are supposed to be worth the same as a dollar), as a way to help people afford things and manage their finances better. This argument is misleading because it suggests that the type of money you use is the problem, rather than the more serious lack of money people face. If a big chunk of the population can't even handle a small unexpected bill, simply giving them access to complicated and risky things like crypto doesn't magically create more money. It just shifts the risk around. If the government thinks that just letting people use these new markets will fix the problem, they're wrong. It will create even bigger problems in the financial system and falsely lead people to believe that gambling in the market is a substitute for a steady job, good credit, and government support.

The crypto affordability myth

To have a real discussion, we need to ask ourselves: What are we trying to fix? The argument is that crypto can help people stretch their limited funds, make transactions cheaper, and help low-income people save money and build credit faster. That sounds appealing, but it focuses on the tools and ignores the foundation needed. Being able to afford things depends on having a stable income, predictable prices for necessities, and access to safe, affordable loans – not on whether you can trade dollars for digital dollars.

The evidence is very clear: lots of families don't have a monetary safety net. In 2024, only about 60% of adults could pay for a small emergency using cash or easily accessible funds. Almost a third couldn't cover their expenses for three months, no matter what they did. According to The Motley Fool, the core challenges around financial vulnerability are more about how income is shared, the job market, and government spending than about how people pay or store their money. Claims that crypto or stablecoins can solve affordability issues also overlook the fact that many stablecoins have proven risky for everyday savers, as seen when some, like TerraUSD, failed to maintain their value. Even if these stablecoins work the way they're supposed to, they just move the risk somewhere else. Just because something is labeled stable doesn't mean that there aren't risks involved, and that big sell-offs won't affect the financial system.

According to a warning from Standard Chartered’s Geoff Kendrick, the rise of stablecoins could drain deposits from banks, particularly regional US banks, and this potential shift is drawing close attention from financial organizations. This shows that they see it as a potential risk to the financial system, and not as a real solution to low wages or lack of social support.

Finally, thinking about affordability in crypto doesn't account for how people will actually use it. People with lower incomes usually don't have as wide a variety of investments as wealthier people do. They have to be careful with their money and avoid risks. Giving them access to things that promise high returns or are very convenient might tempt them to spend the money immediately rather than save it. Allowing risky financial products to be widely adopted can have negative effects: it can encourage people who can't afford to lose money to gamble on investments, and it can take attention away from things that would actually help them, like income support or affordable loans. The decisions that politicians make aren't neutral. Allowing these markets to grow is a form of support that frequently benefits the companies involved more than the people who are supposed to be helped.

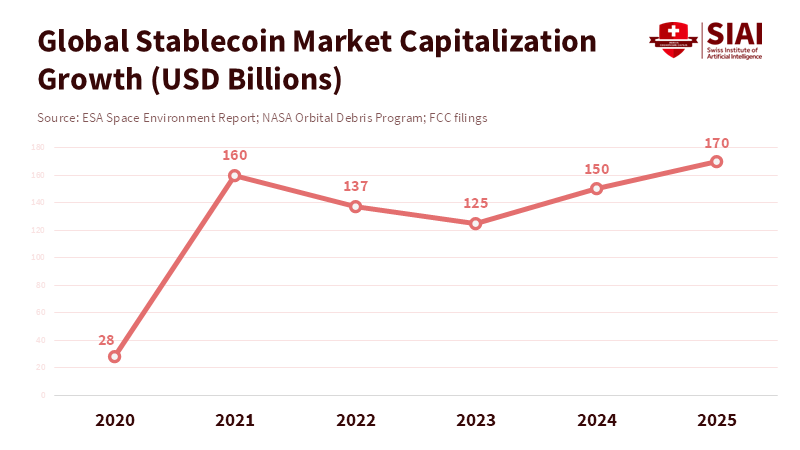

Stablecoins and the shifting of systemic risk

When stablecoins become widely used, the simple idea of being able to exchange the token for a dollar hides a complicated web of connections. Stablecoins connect crypto markets, companies that hold and manage the assets, and the traditional banking system. This is a problem because things that are called stable can still be very concentrated in practice. Experts predict that the total value of stablecoins could be in the hundreds of billions, with just two coins, USDT and USDC, making up most of that total. These are big numbers. If people suddenly lost faith in a large stablecoin issuer, or if investors decided to move their money into tokenized form, it could take money away from bank deposits and short-term lending markets. The quick and easy way to convert stablecoins back to dollars, which renders them appealing for trading, can make problems worse if everyone tries to cash out at the same time.

This wouldn't necessarily be a disaster in every situation, but there are three ways this could realistically cause problems. First, if many people try to redeem their stablecoins at once, issuers might have to sell their assets quickly, which could cause prices to fall and create broader market problems. Second, banks that have lent against tokenized assets or hold balances for these companies could see their loan-to-deposit ratios change, potentially tightening lending. Third, if the government treats token issuers differently from banks, it could create a situation in which uninsured token claims are effectively converted into bank liabilities during a crisis. These problems could disproportionately affect individuals with limited credit, savings, and cash flow, who are more likely to face higher borrowing costs as banks reduce lending.

Another error is the belief that stablecoins eliminate speculation in the cryptocurrency market. According to the IMF Blog, the growth of certain financial instruments stems from their convenience for traders and institutions; however, this expansion does not necessarily translate into transparent or regulated lending opportunities for low-income individuals. Instead, it frequently results in faster trading in markets that remain fundamentally unstable: leverage can increase more rapidly, and networks can become more complex. The ironic thing is that regulators who are trying to protect consumers by creating formal markets could end up creating new ways for stress to spread through the financial system, which would hurt the very people they're trying to protect. Organizations such as the IMF and central banks now view the growth of stablecoins as a potential threat to the financial system, rather than merely a sign of progress.

Policy priorities: rebuild income, not markets

If the main issue is that families are financially insecure, the solution needs to be direct. The first step should be to increase incomes. Raise minimum wages, strengthen labor protections to reduce unpredictable earnings, and reduce risks by gig arrangements that involve precarious scheduling. These steps reduce the desire for risky substitutes because predictable pay allows people to save and manage credit. Second, expand targeted cash payouts: during financial stress, giving people small amounts of money quickly is more effective than giving them access to risky assets. Third, fix issues with credit systems. It is important to create low-cost, clear options for small loans and expand options to help people build credit without trapping them in expensive payday loans or overdraft fees. These aren't unrealistic ideas; they are practical and cheaper than repeatedly rescuing the system when it collapses.

What role should crypto play? A very limited one. Use tokenization to mitigate issues with remittances, verified payments, or international payments. However, do not treat tokenized dollars as a shortcut to cost-effectiveness. Where stablecoins are issued by banks, align the rules: require liquid reserves, require clear auditing, and limit risks within token structures. It's important to set limits on how involved these institutions can be in crypto, given their capital and liquidity, to ensure that token adoption doesn't replace core banking stability. If politicians want the private sector to encourage inclusion, they must design it as an addition to, not a substitute for, support for families.

Some people will immediately argue that stablecoins reduce the costs of remittances and increase access in areas where banking is limited. That is true in some cases, but the questions change at a larger scale. While pilot programs using tokenized options may showcase new technology, they do not guarantee that widespread adoption will improve living standards. A report by researchers, including Yiheng Sun, notes that innovations such as the TransBoost algorithm have improved financial inclusion by enhancing credit risk evaluation, underscoring how advances in financial technology can expand access to credit. That's also true, but access without affordability can create debt. Evidence from studies indicates that many people respond to emergencies by borrowing money or selling assets. Tokenization risks creating new forms of short-term credit unless legal and consumer protections accompany these options. Regulation should be done step by step. Protect basic income and credit first, then permit token use under robust safeguards.

The easy test reveals something. According to research from the JPMorganChase Institute, more than 90 percent of U.S. households can cover a $400 emergency expense, including most lower-income families. While stablecoins and other tokenized financial tools may improve some payment systems, they do not address the fundamental need for stable earnings, predictable costs, or strong family finances. Even worse, uncontrolled market growth risks shifting problems to the institutions that give credit to small and low-income areas. The correct path is the opposite of what's currently being presented. First, prioritize job stability, targeted cash buffers, and affordable, transparent credit. Then, only allow tokenization to grow within a system that limits risk and enforces integrity. We should promote growth in innovation, but not confuse it with real solutions. The goal must be to build a society where people can handle small problems without relying on speculative hope. Only then may we have an affordability policy that stands up to evidence and scale.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2025) Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2024: Results from the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED). Washington, DC: Federal Reserve.

CoinGecko (2025) Global cryptocurrency market and stablecoin market data report. CoinGecko Research.

DeFiLlama (2025) Stablecoin market capitalization data and analytics. DeFiLlama.

International Monetary Fund (2025) Global Financial Stability Report: Crypto Assets Monitor and Financial Stability Implications. Washington, DC: IMF.

Ritz, B. (2024) ‘No, Bitcoin won’t solve our national debt’, Forbes, 31 July.

Reuters (2026) ‘U.S. household debt and credit trends: New York Fed report’, Reuters, January.

Tether Ltd. (2025) USD₮ Quarterly Market Report Q4 2025. Tether Holdings Limited.

Yahoo Finance (2025) ‘Crypto won’t fix America’s affordability crisis’, Yahoo Finance Opinion, 11 January.

Comment