Rewiring Appetite: How Multi-Pathway Obesity Drugs Redefine Clinical and Educational Priorities

Input

Modified

Appetite is not a single switch but a network that can now be powerfully overridden Multi-pathway obesity drugs deliver record weight loss while introducing new biological risks Policy and education must adapt as fast as the science does

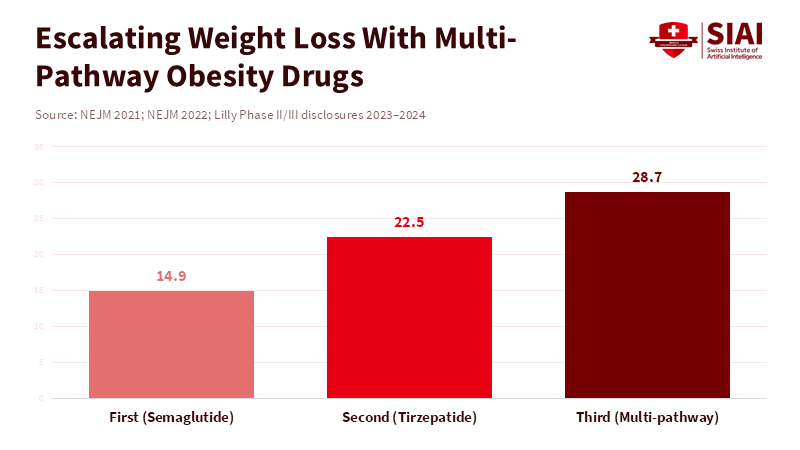

Recent phase III trials examined a new obesity drug that acts on three distinct receptors in the body. The results were pretty amazing: people lost an average of almost 29% of their weight over about a year and a half. You used to only see numbers like that after having surgery to reduce the size of your stomach. This is a big deal, and it should change the way doctors are taught, how patients are treated, and even the rules and policies around these drugs. These aren't just pills that make you less hungry. They actually work on several hormones in your body at the same time. They make you feel less hungry, change the way your body handles nutrients, and can even make you burn more energy when you're resting. According to a review in The BMJ, new obesity drugs that act on multiple pathways can affect your body's normal balance in different ways, so it is important for medical professionals to be aware of these changes. We can't just let students and new doctors learn about these changes little by little. We need to change the way we teach, create easy-to-follow treatment plans, and make sure that the rules protect people's muscles, bones, and overall health while still helping them lose weight.

The old way of thinking about weight loss is outdated

For a long time, doctors have taught that appetite is like a single switch: eat less, move more, and you'll lose weight. That's how people were told to diet and how public health messages were written. But then semaglutide came along and showed that a hormone in your gut could be turned into a weekly shot that really helped people lose weight. Then, tirzepatide showed that if you added another hormone, GIP, it worked even better. Now, there are drugs that combine GLP-1, GIP, and glucagon into one pill. This doesn't just make the drug stronger; it changes how it works completely. These drugs not only reduce appetite but also alter how the liver and muscles use energy. They even affect the parts of your brain that control reward and habits. Teaching new doctors that appetite is merely a single switch will give them the wrong idea. Instead, they need to learn about how all these hormones and receptors work together and how these drugs can have bigger effects than you'd expect.

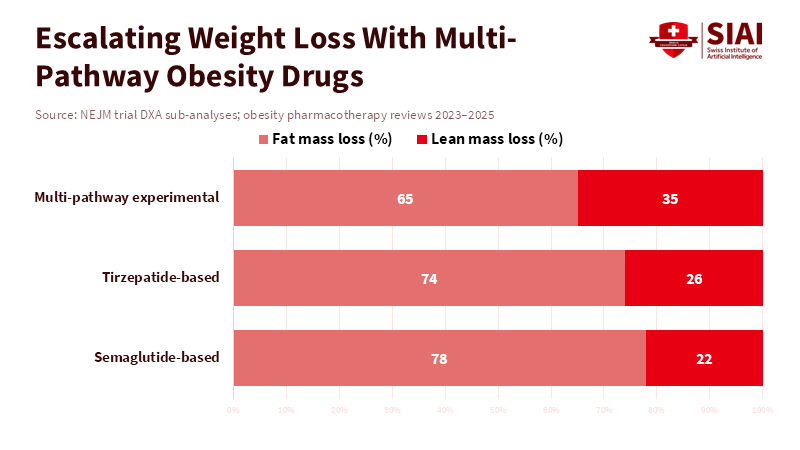

This change is important for classrooms and hospitals because a drug that affects so many things at once can change the risks and benefits. Losing more weight can help with diabetes, high blood pressure, and sleep apnea. It can also change where your body gets energy from when you lose weight. This can cause you to lose more muscle in some cases. So, teachers need to make sure they're teaching not just the basics of how drugs work but also how to measure and protect a patient's overall health. They need to teach practical skills like reading body scans, creating simple exercise programs, and setting protein goals. Students should also be able to understand research studies so they don't just see the big numbers and think that's how it will be for everyone.

The weight loss numbers are pretty impressive, and they're changing the way policymakers think. Semaglutide led to average weight loss in the mid-teens. Tirzepatide made those numbers even higher. And now, these new triple agonists have shown average weight loss in the mid-20s to near 29% in some groups. Again, these are just averages, and not everyone will see the same results. Still, these numbers affect how insurance companies make decisions and how guidelines are written. If teachers and decision-makers see these numbers as guaranteed wins, they might ignore the potential downsides. The best way to deal with this is to teach how the body controls appetite and how to balance weight loss with protecting overall health.

It's not only about the scale

Losing weight quickly can be good for many patients. According to a recent meta-analysis, GLP-1 receptor agonists have been shown to improve blood sugar levels and reduce breathing problems during sleep by significantly decreasing the number of apnea events. Additionally, these medications may cause significant weight loss. However, losing weight too rapidly may risk losing muscle mass. Muscle is important for strength, staying independent, and storing energy. Some reports suggest that the amount of muscle you lose can depend on the drug you're taking. These differences are really important. They can affect your risk of falling, how well you recover from illnesses, and your long-term health, especially for older people and teenagers who are still growing. So, education needs to focus on what's happening with your body composition, not just the number on the scale.

If you want to get the most accurate information about body composition, you need to get a DXA scan. These scans can show how much fat and muscle you've lost or gained. Other methods, like bioimpedance, are easier to use but less accurate. In places where resources are constrained, doctors can use things like handgrip strength, timed walking tests, or calf circumference to assess for early signs of muscle loss. Teachers should teach a variety of methods so doctors can take action even if they don't have access to fancy equipment.

We also need to think about what happens after people stop taking these drugs. While you're taking the drug, your body is in a forced state. Some people quickly gain the weight back after they stop. This shows that these drugs are often just forcing your body to stay at a new weight rather than permanently changing your metabolism. This raises questions about long-term treatment, costs, and the extent of patients' control over their own bodies. For now, it's best to combine the drug with regular exercise and healthy eating plans. This helps protect your overall health while still getting the benefits of weight loss.

What needs to be done

The healthcare system needs to act fast. Primary care doctors are already busy and often lack training in body composition. Short, practical training sessions may help. These sessions should teach when to start medication, how to understand body composition results, and how to create and monitor exercise plans and protein goals. This training should be based on real-life cases and should include nurses, pharmacists, and other healthcare workers. There should also be tools to help patients and doctors make decisions together by explaining the benefits, risks, and monitoring that's needed in simple language. This saves doctors time and makes sure patients understand what they're getting into.

Policies are just as important as education. If insurance only covers the drugs but not the services that protect patients, it creates the wrong incentives. According to a recent analysis published in 2025, expanding access to obesity medications can reduce obesity-related health problems, but it may come with substantial costs over a decade. This suggests that programs bundling medication with support services like exercise, nutrition counseling, and regular health monitoring may help improve outcomes. The report also draws attention to the importance of tracking long-term effects—such as bone fractures, muscle loss, pregnancy outcomes, heart conditions, and changes in weight after stopping treatment—through government-mandated registries.

It's important to be fair to everyone. If decisions are left to the market, wealthier patients will be the first to access the newest drugs and the best services. Public programs should avoid creating a system where the rich get care that protects their health, while others just get a prescription. Education programs should teach doctors who work in resource-limited areas how to monitor patients and give exercise advice. These steps help reduce harm and make sure everyone can benefit from these new treatments.

From Breakthrough to Responsibility

According to a study published in JAMA Surgery, while new multi-pathway obesity drugs have expanded treatment options, bariatric surgery may still provide more effective and longer-lasting results at a lower cost for managing obesity. This creates a lot of hope yet also some real risks. The optimal strategy is to adjust rapidly. Update medical and healthcare training now. Make sure people know how to understand body composition. Connect coverage to bundled care that exercise and nutrition services. Create registries that follow patients for years and include older adults, teenagers, and varied communities. Fund studies that test health, as well as weight and heart health. When we do these things, we can get the most benefit and reduce the risk of harm. If we don't act, we risk trading short-term weight loss for long-term health problems.

There are steps we can take right now. Start with short training updates. Create two-hour, case-based sessions for trainees. Use clear examples of different patient types. Teach how to read a DXA report. Teach how to create exercise plans and set protein goals. Teach simple monitoring schedules and signs that someone needs to see a specialist. Use telehealth for frequent check-ins. According to the Clinical Trials Registry for obesity counseling and diabetes care, it can be beneficial to combine new obesity medications with scheduled healthcare visits and to begin patient registries at the same time. Learn quickly. Change guidance as new information comes out.

We need to measure what's important. Track fractures. Track pregnancies. Track health. Track long-term weight trends and outcomes after people stop taking the drugs. Share registry data. Fund studies that include diverse populations. These steps are doable, and this is urgent. Act now. Keep it simple. Train fast. Test often. Share results. Protect muscle. Be fair. Teach now. Start today.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

ClinicalTrialsArena (2025) Lilly’s triple-agonist retatrutide delivers nearly 30% mean weight loss in late-stage trials. ClinicalTrialsArena.

CNBC (2026) 2026 is shaping up to be the year of obesity pills from Novo Nordisk and Eli Lilly. CNBC.

JAMA Surgery (2024) Comparative effectiveness and cost outcomes of bariatric surgery versus pharmacological obesity treatments. JAMA Surgery.

Jastreboff, A.M., et al. (2022) ‘Tirzepatide once weekly for the treatment of obesity’, New England Journal of Medicine, 387(3), pp. 205–216.

Jastreboff, A.M., et al. (2023) ‘Triple-hormone-receptor agonist retatrutide for obesity’, New England Journal of Medicine, 389(6), pp. 514–526.

National Institutes of Health (2024) ClinicalTrials Registry: obesity pharmacotherapy and integrated care models. NIH.

NPR (2026) New obesity drugs point toward precision medicine for weight loss. National Public Radio.

Ryan, D.H., et al. (2023) ‘New pharmacological approaches to obesity: metabolic benefits and functional risks’, Obesity Reviews, 24(9), e13592.

Scientific American (2025) New GLP-1 weight-loss drugs are coming—and they’re stronger than Wegovy and Zepbound. Scientific American.

Wilding, J.P.H., et al. (2021) ‘Once-weekly semaglutide in adults with overweight or obesity’, New England Journal of Medicine, 384(11), pp. 989–1002.

Comment