When Strength Lags Will: Rethinking mobilizable power for Taiwan

Input

Modified

U.S. deterrence in Taiwan now depends less on political will than on mobilizable power Industrial limits in shipbuilding and logistics weaken the credibility of rapid military response Without aligning capacity to commitments, long-held security assumptions risk strategic failure

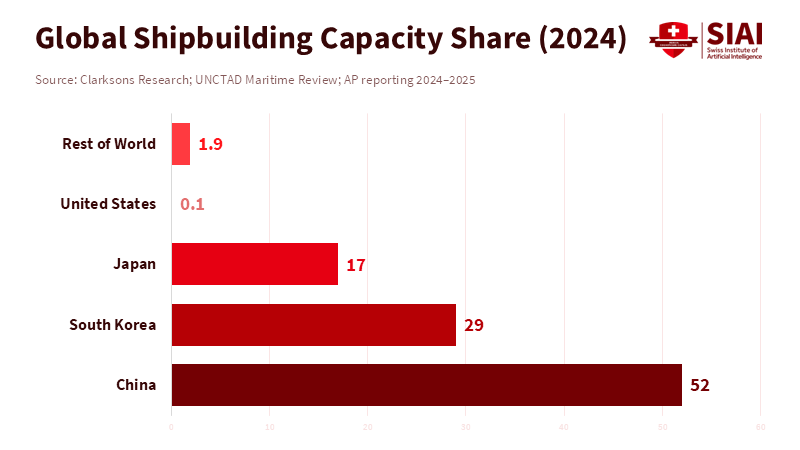

In 2026, a simple fact in manufacturing challenges a long-held belief in East Asia. China is now responsible for making over half of the world's commercial ships, while the United States makes a tiny fraction, about 0.1 percent. This difference isn't just a number; it has real-world importance. A country's naval power depends on its ships, docks, and drydocks, as well as its plans and political intentions. The ability to quickly and reliably turn money and strategy into ships, weapons, supplies, and troop formations is what we call mobilizable power. For many years, people in East Asia have seen the United States' commitment as something they could almost always count on. If a crisis broke out on the Korean Peninsula or in the Taiwan Strait, they assumed the U.S. would intervene with military force. That idea could lead to errors. Mobilizable power is important because preventing conflict depends on taking prompt action, not merely making promises. If a country's manufacturing base, alliance repair networks, ship availability, and preparedness to deploy troops are limited, the gap between declaring an intention to act and actually being able to do so can have disastrous consequences.

The Difference Between Intention and Mobilizable Power

Let's look at the familiar policy debate in a new way. The usual question: Will the United States be willing to fight? – is still important from a political and moral point of view. But it hides a more urgent question: can the United States quickly gather enough forces to make a difference? This difference might seem small, but it's huge in reality. Willingness is a political sign. Mobilizable power is a matter of factories and logistics. If preventing conflict depends on visibly closing the gap between decision-making and action, then those in charge need to focus on their ability to act. Otherwise, threats that could have once been prevented will seem manageable to an opponent who can move faster and get closer to the action.

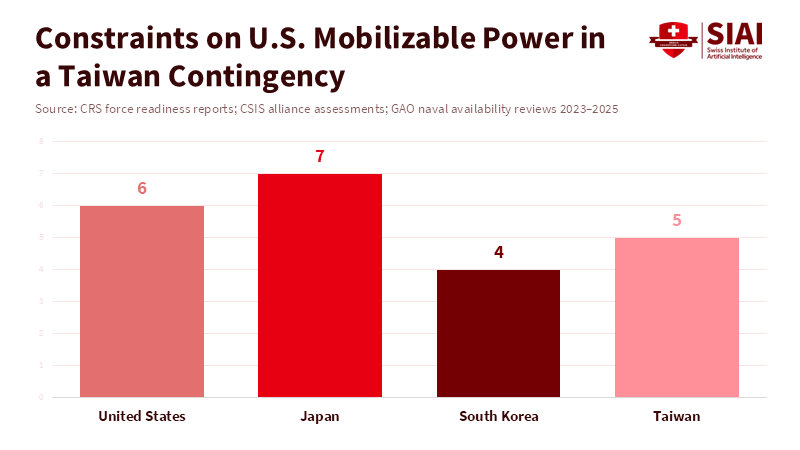

This new perspective matters because several measurable limitations have become worse since 2020. The U.S. has aircraft carriers, but many are regularly undergoing maintenance. The number of amphibious ships falls short of set goals, and they are often not ready. The U.S. shipbuilding industry can't quickly increase commercial ship production without causing problems elsewhere. Allies like Japan and South Korea can help, and they already do much of the heavy industrial work. But relying on allied shipyards or forward repair facilities isn't the same as having your own industrial capacity that can be quickly mobilized in wartime. That difference is the key to mobilizable power: the ability to turn peacetime resources into wartime support.

Decision-makers who only ask, " Do we want to act? will not properly prepare educators, trainers, logistics personnel, and procurement officials. They will teach military students about high-level strategy but ignore the details of providing support. Schools and service academies need to broaden their curricula to include the economics of mobilization, diplomatic relations with allies on industrial matters, and logistics for unforeseen events. Administrators must practice making political choices that trade immediate presence for the ability to increase capacity quickly over the long term. And officials must stop treating shipyards and drydocks as mere budget items; they are force multipliers and potential points of failure. These topics might not be exciting, but they are where wars are won or lost.

Shipyards, Carriers, and the Industrial Obstacles to Mobilizable Power

Shipbuilding is the hidden factor that determines naval options. China's advantage in commercial shipbuilding confers practical leverage: faster construction, lower costs, and a large pool of skilled maritime workers. Recent reports and analyses have directly linked this supremacy to national security risks, as commercial capacity supports repairs, auxiliary shipping, and the overall logistics chain. The U.S. industrial capacity for commercial ship production is now so small that policy planners are openly talking about partnering with East Asian shipyards or encouraging foreign investment in U.S. facilities. This approach is helpful, but it also shows the blunt reality: the United States doesn't have the same ability to increase wartime capacity as it once did.

The impact on operations is clear. The U.S. Navy has about a dozen nuclear carriers on paper, but at any given time, roughly half are in port or undergoing major repairs. Carrier availability is a matter of timing: building and maintaining their aircraft, escorts, and logistics support takes time. Meanwhile, amphibious readiness – important for any intervention in the Taiwan Strait – has declined. The fleet of amphibious vessels is close to the minimum required, and maintenance delays often reduce the number of deployable units. When planners create scenarios for rapid intervention, they often assume a level of forward presence and support that the current industrial base cannot guarantee without help from allies or a major reallocation of national resources.

All of this changes the balance between distance and speed. An opponent who can position forces just outside the area of conflict forces defenders to act faster. Mobilizable power is therefore less about winning a single decisive battle and more about the time it takes to assemble, repair, and support the tools of war: escorts, supply ships, weapons, and temporary airfields. If these parts can't be moved or repaired quickly in the area of conflict, political will might come too late. For educators and training commands, the message is clear: war colleges must teach operational art that treats industrial policy as a practical reality. Administrators must create simulations that include multiple sectors, with shipyards, ports, and civilian logistics as active participants in contingency plans.

Rethinking Alliance Agreements: Shared Deterrence and Practical Solutions to Mobilizable Power

If we agree that mobilizable power is the limiting factor, then the policy response must be practical and involve multiple parties. First, invest in defenses on Taiwan's periphery that are difficult to target: anti-access systems, mobile strike capabilities, and secure logistics hubs that make a rapid campaign of coercion more difficult. These tools make it harder for attackers and reduce the immediate need for large external forces. Second, establish lasting shipyard partnerships with Japan and South Korea that go beyond political gestures to legally binding commitments on repair access, priority work during crises, and worker training. Third, increase pre-positioned supplies and integrate civilian and military resources at ports across the Indo-Pacific to ensure replenishment is not bottlenecked in a few shipyards.

These ideas aren't new, but they require a difficult political conversation about trade-offs. Critics will say that official industrial commitments risk escalation or the giving away of sovereignty. They will instead demand that the United States rebuild its domestic capacity. Both points have some truth. Rebuilding U.S. shipyards is necessary but slow and expensive. Partnering with trusted allies buys time and increases capacity more quickly. A sensible approach is a mix of both: a solid program to rebuild domestic shipbuilding, combined with legally valid agreements with allies that guarantee access and prioritize repairs during a crisis. These agreements must be based on clear, public rules and tested in exercises under stress. Evidence of allied commitment can be created through predictable industrial coordination rather than through political statements that might not hold up in a crisis.

For educators and administrators, this policy shift means teaching networked logistics and alliance negotiations as essential skills. The curriculum should include case studies of economies that quickly increased production, port management under stress, and the regulatory provisions that allow civilian shipyards to accept military work in contested environments. For decision-makers, the lesson is operational: deterrence is only as good as the industrial pipeline that supports it. If we want others in the region to continue relying on U.S. redlines, we must make those redlines credible with respect to industrial capacity, not just words.

Addressing Criticisms and Closing Practical Gaps

A common counterargument is this: if the United States can't meet every need on its own, then relying on allies and Taiwan itself weakens deterrence by signaling division. This criticism is based on a narrow view of deterrence as a single show of force. Instead, we argue for layered deterrence. Distributing capacity across allies and enabling Taiwan's own defenses, which are difficult to target, can create a combined cost that outweighs any single political calculation. The evidence is mixed, though informative: recent arms packages and investments in systems that are difficult to target have made Taiwan harder to seize quickly, while shipyard investments and MOUs driven by partners have started to expand repair options in the region. These are small but important steps toward greater mobilizable power.

Cost and political willingness are real limitations. Rebuilding shipyards takes decades and billions of dollars. Binding allies into industrial commitments requires legal work, trust-building, and believable political signals in peacetime. Yet the alternative is more fragile: a strategy that hopes political will will always match capacity. That hope has weakened in recent years due to competing global priorities, a stretched military presence, and domestic political instability. The practical response is to rebalance policy tools: accept that the U.S. won't be able to provide an endless number of ships overnight, but don't give up on deterrence as a result. Invest in the specific measures that accelerate mobilization: joint repair protocols, forward spare-part caches, incentives for industries to handle both civilian and military needs, and frequent drills with all branches of the military and allies that exercise the entire pipeline from political decision to operational support. For educators, teach students to think in terms of these practical measures instead of abstract ideas of will.

Build the Means that Match the Message

We started with a hard fact about manufacturing because a strategy without capacity is weak. If deterrence in East Asia continues to assume that declarations of intent will automatically turn into timely force, it invites miscalculation. Mobilizable power is the connection between words and action. To fix that, a connection requires honest assessment, curriculum changes, and policy choices that favor shared, allied industrial cooperation alongside a long-term domestic rebuild. Teachers must teach it. Administrators must plan for it. Authorities must fund and secure it. Only through aligning our means with our messages can we make deterrence lasting and responsible. The question isn't whether we want to defend partners; it's whether we can get there in time. The answer will determine whether promises in the Pacific remain a deterrent or become dangerous illusions.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Associated Press (2025) US seeks shipbuilding expertise from South Korea and Japan to counter China. Associated Press.

Atlantic Council (2025) Can US leaders convince Americans that Taiwan is worth fighting for? New Atlanticist, 18 December.

Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) (2025) Identifying pathways for US shipbuilding cooperation with Northeast Asian allies. CSIS Analysis, May.

Congressional Research Service (CRS) (2024) Navy force structure and shipbuilding plans: Background and issues for Congress. Washington, DC: CRS.

Defense Priorities (2025) Target Taiwan: Challenges for a US intervention. Defense Priorities Report.

East Asia Forum (2026) Taiwan has misplaced confidence in Trump’s national security strategy. East Asia Forum, 7 February.

Economy.ac (2026a) US strategic capacity and alliance constraints in East Asia. Economy.ac, 28 February.

Economy.ac (2026b) Industrial limits, naval capacity, and defence mobilization. Economy.ac, 28 January.

Government Accountability Office (GAO) (2024) Navy needs to complete key efforts to better ensure ships are sustainably available. GAO-25-106728. Washington, DC: GAO.

Kim, S. and Roll, R. (2025) Alliance capacity and industrial constraints in Northeast Asia. Korea Economic Institute Policy Paper.

MIT Security Studies Program (2025) Considering a US-supported self-defence option for Taiwan. MIT SSP Analysis.

US Naval Institute News (USNI News) (2025) Fleet and Marine Corps readiness and maintenance updates. USNI News.

War on the Rocks (2025) How South Korea can help the US Navy stay afloat in the Pacific. War on the Rocks, 12 November.

Comment