Faster, Not Fresher: Why state-dependent pricing Explains the New Speed of Inflation

Input

Modified

Inflation spreads faster because firms reprice in response to shocks, not calendars Energy and AI amplify this speed, but state-dependent pricing is the core driver Policy and education must adapt to inflation that moves in days, not months

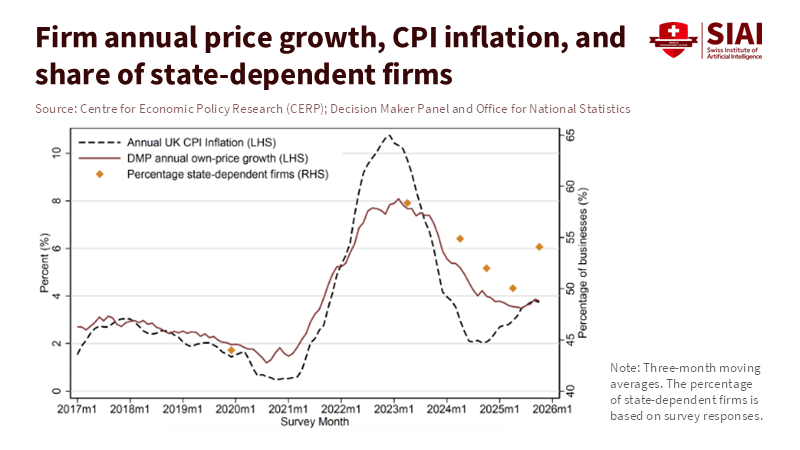

Inflation isn't just creeping up anymore; it's running wild. Since 2023, most companies report they're adjusting their prices when events occur, not just on a set schedule. A recent study found that approximately 54% of businesses adjust prices in response to changing conditions rather than at set intervals. This change transforms sudden problems into rapid price cascades that spread across multiple products and even to other countries. This isn't just a minor detail. When companies respond to events, a price increase for a necessary input can quickly affect everyone from suppliers to stores within days or weeks, rather than months. This makes energy price spikes, cost changes caused by computer programs, and even short-term supply problems much more powerful. The main point is this: recent fast inflation isn't just about shipping or the news being faster. It concerns a fundamental change in how companies set prices, called state-dependent pricing, and how that change makes energy and technology problems become major issues for decision-makers.

State-dependent pricing acts like a transmission amplifier

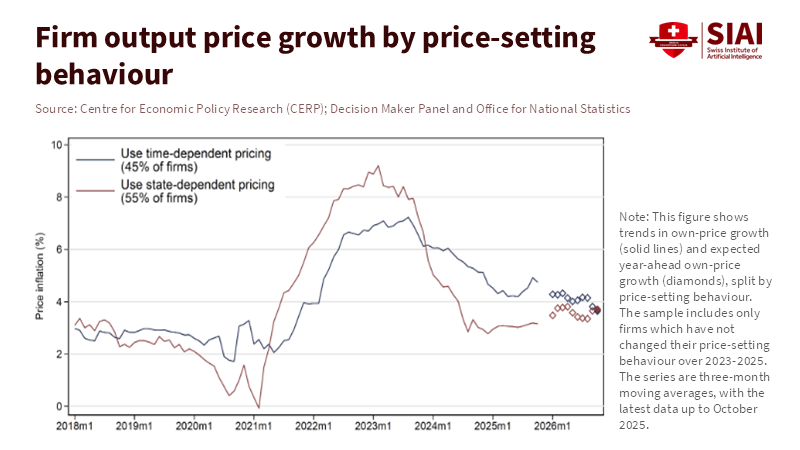

Historically, people thought prices mostly changed on a set schedule, so it took a long time for those changes to affect the economy. But new information shows that's not true anymore. Large-scale surveys of companies across the economy and recent research papers indicate that an increasing number of businesses are adjusting prices in response to events. Companies report that factors such as uncertainty, nonlabor costs, and the extent to which their industry is affected by costs increase the likelihood that they will adjust prices when conditions change. When lots of companies do this at the same time, problems don't just stop with the first group of contracts; they spread everywhere. A supplier that raises its prices due to increased fuel costs causes distributors to raise their prices as well. Then, stores that experience changes in cost and profit pressures adjust their prices for customers. This creates a chain reaction of adjustments that reduces the time between a problem and its full effect on consumer prices. This is the main thing that people noticed during the inflation period of 2021–23.

The effects are real and noticeable. Studies examining different industries and how they're connected show that energy problems in 2021–22 led to broader inflation much faster than in the past. These studies estimate that large increases in energy costs contributed substantially to overall inflation, both directly through household energy bills and indirectly through the production of goods. The best way to determine this is to combine surveys of companies (to see how they set prices) with models that show how cost changes propagate through the production process. When surveys indicate that more companies use state-dependent pricing, models that incorporate real-world industry linkages show that the economy responds more quickly and strongly to the same problem. State-dependent pricing doesn't occur only with faster changes; it amplifies them because of how industries are connected.

This idea has two important considerations when examining policy. First, when making predictions, we can't assume that outcomes will occur at a fixed time. The timing of a problem matters because the factors that prompt companies to take action (such as running out of inventory, reaching cost limits, or experiencing sales declines) can vary and occur together. Second, policy tools that take a long time to work, like assuming that changes to money supply will slowly reduce demand enough to fix inflation, without hurting the economy, are riskier when prices react quickly. Models must include state-dependent triggers; otherwise, they may fail to accurately estimate the speed and magnitude of inflation. Recent research papers that combine surveys with economic models make this clear: when more companies use state-dependent pricing, the economy's responses to problems are faster and more pronounced.

There are two stories that compete— energy and AI — and how state dependence sorts them

Public discourse on recent inflation has focused on two main ideas. The first concerns traditional supply shocks, which are sudden, large increases in energy costs during 2021–22 that raised producer profits and consumer prices. The second idea points to new technological problems, such as rapid, AI-driven changes in productivity, how companies procure materials, and how they enforce contracts, which alter supply conditions across industries in novel ways. There's some truth to both stories, but they suggest very different things for policy. To make good choices, we have to understand how each one interacts with state-dependent pricing.

Energy shocks often cause state-dependent chains of reactions. Examining specific industries and using frequent energy price data and inter-industry linkages shows that large increases in fuel prices raise production costs for energy-intensive firms. Those companies then adjust their prices more quickly when they have small profits or when demand is changing. Some studies estimate that, in recent years, a large energy spike could account for a much larger share of the increase in overall inflation than in the past, because price changes propagate through production networks more quickly. The way to figure this out is clear: combine real energy price changes with how much each industry spends on energy and how likely they are to pass those costs on to customers. Where companies report being more likely to make state-driven changes, the same energy shock has a larger effect on overall inflation. This aligns with what occurred globally in 2021–22, when jumps in gas and oil prices coincided with rapid price changes across many product categories.

AI-driven shocks are more complex but may persist longer. New technologies change how companies get materials, how they combine services, and how quickly they notice when profits are falling. For example, computer programs that automatically adjust prices and real-time supply-chain optimizers shorten the time between problem detection and price adjustment. When an AI tool makes it easier to find information or automates dynamic pricing, a short-term change in costs or demand can cause instant price adjustments across the economy. Some early reports and surveys suggest that AI creates supply and productivity shocks that spread quickly: when one company's productivity changes, it immediately affects its competitive position, causing price changes at related companies. The problem is that AI effects vary and persist, so we must use case studies and surveys of specific companies to estimate their magnitude. Those early signs suggest that when AI-driven decision tools are used by companies that already employ state-dependent pricing, the speed of price changes increases further. In simple terms, AI shortens the time between noticing a problem and acting on it, whereas state-dependent pricing determines whether that action triggers a chain reaction across the economy.

Putting the two ideas together makes an important point clear. If state-dependent pricing were rare, even large energy shocks would fade more quickly, causing widespread inflation. Likewise, AI-driven price changes ina context where prices are set on a schedule would have more limited, local effects. But the combination we see, which is more companies using state-dependent pricing plus faster technology-driven decision tools, creates a multiplier effect. So, those in charge must stop thinking about single causes. The speed of inflation in 2021–25 is best explained by a combination of energy shocks, AI-driven changes in business operations, and a shift toward state-dependent price-setting. This explains both the speed and the uneven patterns we've observed across countries.

What educators, administrators, and policymakers have to do

First, education planners and administrators have to update how they teach about how prices change. What they teach matters because future analysts and public managers need models that understand state dependence, how problems get bigger through connections, and how quickly technology is used. This means introducing examples and activities that connect how companies set prices with how industries are connected. Simple simulations, which allow students to change a fuel price and see how prices set on a schedule versus state-dependent pricing change the results, show the idea much better than static graphs. This change in teaching is low-cost and has a big effect: it changes thinking about lag structures and policy timing and better prepares the next generation of central bank and government staff to understand high-frequency data. This is pressing because misunderstanding the speed of change can cause big problems for people.

Second, administrators in government buying and education supply chains should add monitoring points. If prices can spread in weeks, institutions need to collect cost data from suppliers more often, especially for things that use a lot of energy, like transport, catering, and materials. This doesn't mean endless reporting; it means targeted, monthly reviews for things that are high-risk and simple trigger-based rules. Methodologically, combine what you have observed from sharing input with supplier margin exposure to estimate the possibility of an urgent repricing event.

Third, policymakers and central banks must adjust their frameworks and communications. Because of state-dependent pricing, price changes are slower, giving less time. That means three specific shifts. One: Models used for policy should include state-dependent causes and estimates of how problems spread through networks, based on recent company surveys. Two: Central banks must explain it so people understand it better. Three: Fiscal supports should be ready. These are expensive.

Finally, anticipate and answer critiques. One critique: state dependence is just a survey because it doesn't always change. To add to this, we should look at the higher frequency in sales. Another critique: energy explains a lot; a pricing change is needed. The answer is that the models are slower, which can lead to real-world data. A final critique: AI is a guess, which is why policies should be driven by data. Where AI is high, one should watch algorithmically.

The recent episodes of fast-moving inflation force a simple change in perspective. Speed matters. When more firms set prices in response to events, and when digital tools shorten detection-to-action times from months to days, shocks — whether from energy markets or technology-led supply changes — move through economies with greater velocity. That means educators must teach mechanisms, administrators must monitor supply chains in near-real time, and policymakers must build models and institutions that respect conditional speed. The alternative is familiar: delayed understanding, sharper policy swings, and avoidable economic pain. Our window for adaptation is not theoretical; it is now. Use firm-level surveys, sectoral linkages, and targeted monitoring to identify where state-dependent pricing and new technologies intersect, and design policy rules that respond to the speed and shape of shocks rather than to old calendar assumptions. The task is not to stop shocks—often impossible—but to prevent them from becoming policy-crisis amplifiers.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). 2024. Why inflation may respond faster to big shocks: The rise of state-dependent pricing. VoxEU Policy Platform.

Bank of England. 2026. State- and time-dependent pricing. Bank of England Working Paper.

International Monetary Fund. 2025. The energy origins of the global inflation surge. IMF Working Paper No. 25/091.

LSE Business Review. 2025. AI is changing inflation dynamics and challenging central banks. London School of Economics.

Office for National Statistics. 2024. Consumer price inflation and producer price dynamics. Statistical Release.

Comment