Stablecoins and the New Exorbitant Privilege of Private Money

Input

Modified

Payment stablecoins now hold a quiet form of monetary privilege It comes from settlement design, not true money creation Until issuers are regulated as banks, the system remains distorted

In 2024, stablecoins used for payments handled trillions of dollars in transactions worldwide. The assets these stablecoins held as reserves would make some of the issuers larger than some of the largest money-market funds. But, unlike banks, these companies don't lend money in the usual way. They also aren't watched as closely as banks and can't borrow money from a central bank if they're in trouble. This situation isn't just some minor detail; it's a big problem that's creating a new imbalance in the money system. History teaches us a lesson: monetary systems can collapse when groups create assets that function like money but don't follow the same rules as traditional financial institutions. The United States became a global power partly because the dollar is used as a reserve currency. Other countries that attempted to replicate this without the same credibility experienced inflation and economic collapse. According to a report from DAOSquare, payment stablecoins have enabled large-scale transactions, with $10.8 trillion settled in 2023, including $2.3 trillion tied to organic activities like payments and cross-border remittances. This isn't just innovation; it's a clear advantage.

The Special Advantage of Stablecoins

The main point here is that payment stablecoins have a special advantage, kind of like having an exorbitant privilege. This advantage doesn't come from being legal tender or having government backing. It comes from how they're designed. Because they're part of the payment process, stablecoin issuers can temporarily control a lot of money. This money acts like real currency, even if it's legally considered a token or a claim. The company that issues the stablecoin earns money during the settlement process, earns interest on its reserves, and increases the amount of money in circulation without issuing loans or following strict financial rules. That's the special advantage they have.

This is becoming a problem as stablecoins gain popularity. By late 2024, the total value of stablecoins in circulation was consistently over $100 billion. One company that issues stablecoins reported profits comparable to those of large regional banks, primarily from interest earned on reserves invested in short-term government bonds. This income isn't from helping people borrow and lend money; it's simply a result of how the payment system is designed. Each stablecoin functions as a prepaid deposit used outside the traditional banking system, yet still relies on people trusting conventional currencies.

The comparison to the special advantage that countries have isn't just a figure of speech. The United States benefits because the dollar is central to global trade and finance. This allows the U.S. to borrow money cheaply and handle economic problems better than smaller countries could. Stablecoin issuers benefit because their stablecoins are used as money, while their underlying assets earn interest with little risk. No developing country could copy this structure without losing credibility. Yet private companies are now doing this on a large scale, without a mandate to manage the money supply or subject to public oversight.

How Payment Systems Create Money-Like Power

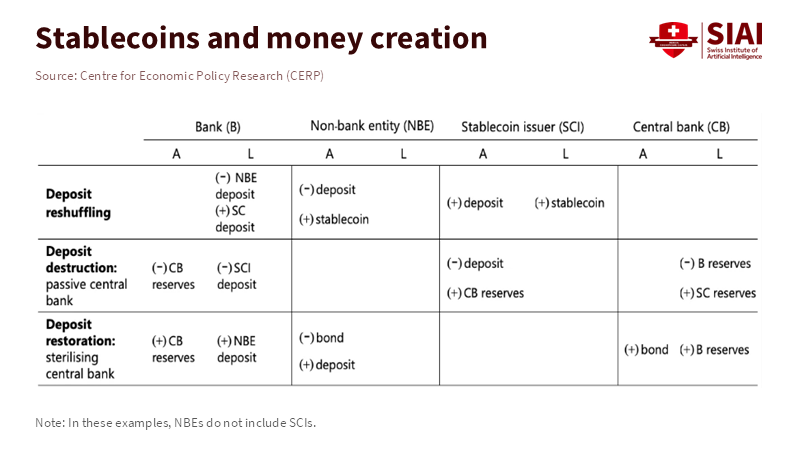

The reason stablecoins have this special advantage isn't complicated. It concerns how quickly payments are settled and how the system is pre-funded. Traditional payments involve moving deposits between banks. Stablecoin payments involve moving tokens that are already outside the banking system. Once these tokens are created, they're used repeatedly before they're exchanged back for regular currency. During this time, the company that issued the stablecoin controls the reserves that back it.

This creates a subtle way to make money, not through loans but by how often the same money is used. The same dollar backs multiple transactions while continuously earning interest. Data suggest that major payment stablecoins are used far more frequently than conventional bank deposits. Even if we're conservative in our assumptions, a stablecoin supply of $100 billion can accommodate a much larger transaction volume without increasing reserves. The company that issues the stablecoin benefits from this without incurring additional financial risk.

According to a report from CRA, the adoption of stablecoins like USDC has not had a significant impact on community bank deposits. When deposits move away from banks, the banks have to reduce their lending or find more expensive ways to fund it. The money doesn't disappear; it's moved to companies that don't lend it out but still make money from it.

Some say that stablecoins are fully backed and therefore harmless, but that's not the whole story. The problem isn't just the risk that the stablecoin company will go broke. It's that banks and stablecoin issuers are treated differently. Banks turn deposits into credit under strict rules, while stablecoin issuers turn deposits into interest under less strict rules. The advantage is in doing less while making more.

The Blind Spot in Education and Regulation

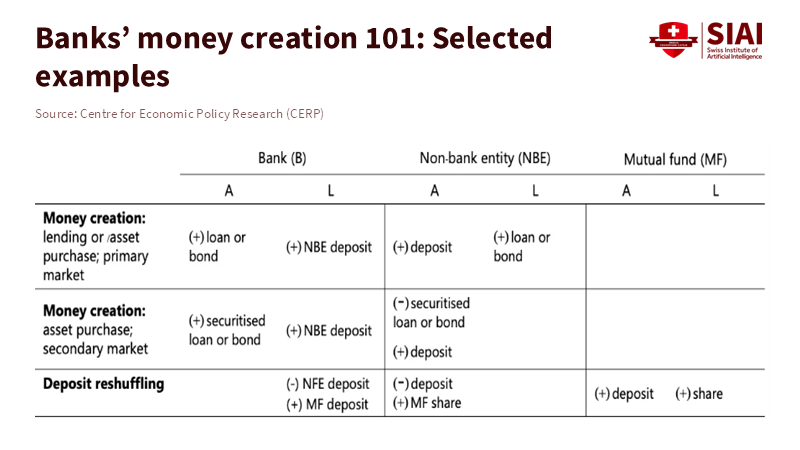

According to Rethinking Economics, many finance courses still teach that banks and central banks are the primary creators of money, even though recent research from institutions such as the Bank of England and the Bundesbank shows that commercial banks create most of the money in circulation. Payment systems are treated as mere tools. But that's no longer correct. Stablecoins have a special advantage because payment systems are now balance-sheet machines.

Administrators and teachers need to choose: either keep teaching about money as static, or teach it as a process determined by the financial system's design. Students studying finance, policy, and public administration need to understand that the way payments are settled can shift power as much as interest rates do. This isn't just a niche topic for crypto enthusiasts; it's a fundamental part of how money works.

Regulators face comparable challenges. They're focusing on the quality of reserves, disclosures, and the ability to redeem stablecoins. These things are important, but they don't address the main problem. According to a report from the Independent Community Bankers of America, if crypto intermediaries are permitted to pay interest on payment stablecoin holdings, this could significantly reduce community banks' deposits and lending, even when these stablecoins are fully backed. This is a structural issue, not just something speculative.

Some worry that forcing stablecoins to operate like banks will stop innovation. But history suggests that innovation happens when the rules are clear. Payment companies can create new and better ways for users to interact with the system, make payments faster, and ensure that different systems can work together. But the creation of money should be limited to institutions responsible for the entire financial system. Until that line is drawn, stablecoins will continue to have a special advantage.

Fixing the Problem: From Tokens to Institutions

The solution isn't to ban stablecoins, but to bring them into the financial system. If stablecoins want to operate at scale, they need to assume the same responsibilities as banks. This means being supervised like banks, holding capital holdings, and having access to central bank lending in exchange for accepting restrictions. This would eliminate the special advantage that stablecoins have by turning private money substitutes into regulated financial institutions.

The other option is to do nothing. As stablecoins become more popular, they'll play a bigger role in payments, international trade, and online finance. The companies that issue them will have more control over money flows without being accountable. We've seen this before when shadow banking grew faster than regulations, and the results weren't good.

It's worth repeating that trillions of dollars in payments are now processed by companies that aren't banks but function as financial hubs. That's not sustainable. Educators need to update their courses. Administrators need to rethink the limits of financial institutions. Policymakers need to act before this special advantage turns permanent. Monetary systems fail not because of new ideas, but because the rules aren't fair. Stablecoins aren't a threat because they're new, but because they have a lot of power without being fully responsible. That's the problem, and it can still be fixed.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank Policy Institute. (2024). Stablecoins, deposits, and bank lending dynamics.

McKinsey & Company. (2023). Tokenized cash and next-generation payments.

Federal Reserve Bank research compilations on digital payments and money markets (2023–2025).

IMF Global Financial Stability Reports (2023–2024).

Comment