What You Believe Is What You See: Reframing Perception for Classroom Truth

Input

Modified

Beliefs shape perception before evidence is even processed Video and data do not correct bias; they often reinforce it Education systems must redesign how evidence is interpreted, not just collected

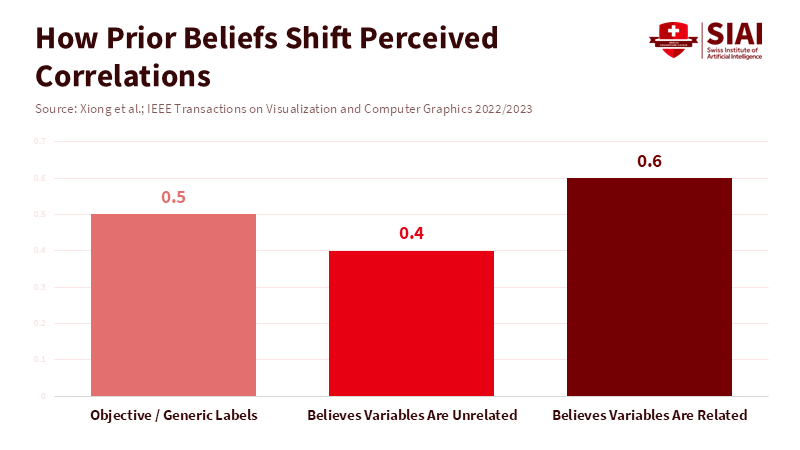

It's not as simple as people seeing the facts first and then figuring out what to believe. Recent studies show that it often works the other way around: what we already believe can change how we perceive things. In one experiment, participants viewed the same data on a graph. The first time, the graph had plain labels. The second time, the labels meant something to the people looking at it. Those who already thought there was a pattern in the data were more likely to see one (by about r ≈ 0.1). Those who didn't think there was a pattern were less likely to see one (about the same amount lower).

This change might not seem like much, but it can really mess things up. It can change how we see evidence, making it seem to back up what we already believe, even if it doesn't. This isn't just something that happens in a lab. It's something we all do—we can call it perception bias. It changes how students, teachers, and school leaders understand videos, charts, and other classroom materials. If we think that videos or data are just showing us the objective truth and don't consider perception bias, we're just making mistakes worse. So, the big question is: how can schools teach in ways that reflect the evidence rather than just what we already believe?

Perception Bias: How We Edit What We See

Instead of saying, " Seeing is believing, maybe we should say believing is seeing. This means the problem isn't with the video or the graph itself, but with how we understand them. We need to consider how our experiences, training, and culture shape how we see and understand evidence. There's a lot of research that supports this.

One idea is that we see things by combining what we expect with what we actually see. If we're really sure about what we expect and what we're seeing is unclear, we're more likely just to see what we expect, even if it's not really there. Experiments have even shown that people can have conditioned hallucinations where they see things that aren't actually there because they expect to see them. When we're not sure about something, our beliefs take over.

This is important for schools because classrooms are full of things that can be understood in different ways. A short video of a class omits significant information. It only shows certain gestures, camera angles, and moments. Teachers have their own ideas about what motivates students, what good teaching looks like, and how to manage a class. These ideas can change how they see things. When a school leader watches a video to decide how to support a teacher, their own ideas about that teacher will change what they notice and how they understand it. We need rules to reduce the impact of our own ideas on how we see things. We can’t just assume that everyone will see the same thing.

How Perception Bias Affects Videos and Data

Right now, two things are making perception bias even more critical. First, videos are everywhere in education. Surveys and reports show that teachers consider videos necessary, and young people watch them online every day. This means we're often making decisions based on short, edited clips rather than watching for a long time. Second, computers and AI make it easy to create convincing but incomplete pictures of what's happening. This can lead us to see what we already believe. The problem isn't just that we might see fake videos. Is a short clip the whole story?

Research shows how this works. Studies have found that people's ideas about relationships can affect how they interpret data on a graph (by approximately ≈ ±0.1). Other studies show that if we believe something strongly, we're more likely to see things that aren't there, and our brains react differently to what we see. This is likely because we pay more attention to information that supports what we already believe, and we adjust our understanding when it is unclear. In the classroom, this might mean we focus on a few moments that align with our idea of what's happening and ignore others that don't. This can trigger a cycle in which our beliefs shape what we see, and what we see reinforces those beliefs.

What to Do About Perception Bias in Schools

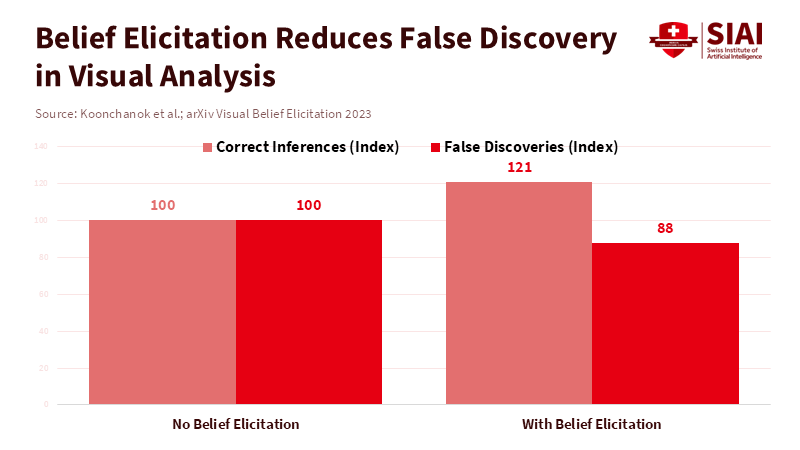

If perception bias is just how we usually understand evidence, then we need to change how schools are organized and how they teach, not just tell people to be more careful. First, we need to change how we watch classroom videos. Instead of having one person watch a short clip and make a decision, we should have teams of people watch the videos without knowing who the teacher is. They should write down what they see before interpreting it. Studies have shown that when people describe what they see before labeling it, they're less likely to be influenced by their own ideas. This can help us see things more clearly.

Second, we need to teach teachers and school leaders about perception bias. This could be short lessons that help them understand their own ideas, encourage them to test them, and teach them to pay attention in a concrete way (e.g., what to look for, how to monitor over time). This training should be hands-on so teachers can see how their own beliefs shape their understanding of the same video.

Third, we need to change the videos and data that we use. When we use videos, we should include information about when events occurred, a summary of what happened before, and a list of what's not shown in the video. According to research by Newman and Scholl, the way labels and visual elements are presented on graphs can influence how people interpret data, sometimes leading viewers to believe that values within a highlighted area are more likely than those outside, even when the difference is only in presentation. Starting with plain labels and encouraging initial interpretation before revealing the true meaning of the data can help reduce this type of perceptual bias. Finally, schools should have multiple people review essential decisions (such as teacher evaluations or disciplinary actions) and ensure there's enough time to observe teachers in different situations, so that a single short video doesn't unduly influence the outcome.

What About People Who Think This Is Too Complicated?

Some people might say that these rules are too much work, take too much time, or don't respect experienced teachers who know what's happening in a classroom when they see it. But research shows that even experienced teachers are affected by perception bias. In fact, their ideas might be even stronger and more influential. The more sure we are about something, the more likely our ideas are to change how we see things. This means that experience can help us see things more clearly when we also get different points of view. But it can also make us focus on only certain things. The answer isn't to ignore experience, but to create ways to test experience by seeing things in new ways. Having different people review things and watch videos without knowing who the teacher is saves time compared to dealing with appeals and the problems caused by bad decisions.

We started with a small number: our own ideas can change how we see data by about r = 0.1. This might seem small, but it can add up when we're making lots of decisions. Schools need to stop thinking that videos and data are just showing us the truth. Instead, they need to understand that these things can be interpreted differently depending on what we already believe. School leaders should require that people watch videos without knowing the teacher's identity, have teams review videos, add information to the videos, and train teachers to understand their own ideas. School leaders should also have different people evaluate teachers and ensure there's enough time to observe them in different situations. Teachers should use videos to gain different perspectives on their own teaching. These steps won't stop people from disagreeing, but they will help us use evidence properly: to test our beliefs, not just to support them. If we want classrooms to show us the real picture instead of just what we already believe, we need to change how we look at things.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Deloitte. (2024). Generative AI and Fraud: Projected economic impacts. Deloitte Advisory Report.

Entrust. (2024). Identity Fraud Report 2025: Deepfake attempts and digital document forgeries. Entrust, November 19, 2024.

Jumio. (2024). Global Identity Survey 2024 (consumer fear of deepfakes). Jumio Press Release, May 14, 2024.

Alliant National Title Insurance Co. (2026). Deepfake Dangers: How AI Trickery Is Targeting Real Estate Transactions. Blog post, Jan 20, 2026.

Tasnim, N., et al. (2025). AI-Generated Image Detection: An Empirical Study and Benchmarking. arXiv preprint.

Group-IB. (2025). The Anatomy of a Deepfake Voice Phishing Attack. Group-IB Blog.

Stewart Title. (2025). Deepfake Fraud in Real Estate: What Every Buyer, Seller, and Agent Needs to Know. Stewart Insights, Oct 30, 2025.

Comment