Between Tokens and Thought: A Fresh Look at AI Awareness

Input

Modified

AI systems produce fluent language through probabilistic pattern learning, not through conscious awareness Equating parameter scale with human cognition confuses simulation with subjective experience Education and policy must treat AI as powerful tools, not emerging minds

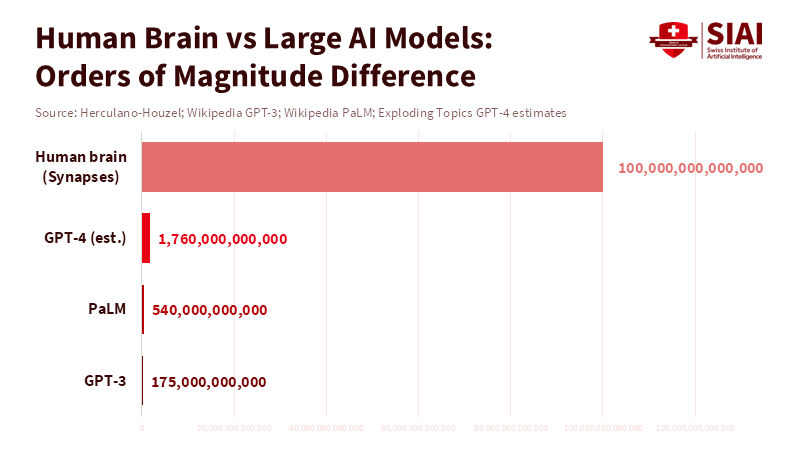

Here's a thought: the human brain has around 86 billion neurons and about 100 trillion synapses. Now, some of the biggest AI language models have hundreds of billions of parameters. It's easy to see why people jump to the idea that AI is becoming aware, thinking that it just needs to get bigger to reach consciousness. Just because the numbers are similar doesn't mean AI is actually like a brain. There are big differences in how they're put together, how they work, and what they can do. A parameter in an AI model isn't the same as a neuron in your brain. And predicting the next word in a sentence is totally different from feeling emotions, having goals, or being aware of yourself and the world around you. AI works by spotting patterns in data. Our brains, on the other hand, are biological systems that change over time and are connected to our bodies. This creates our awareness. So, what does this mean for teachers and those who make the rules about AI? They need to take action now because AI is changing society so quickly, and there are many ethical questions to consider.

What People Say AI Awareness Is—and What These Models Actually Do

People who support AI and those who worry about it often point to the same thing: AI language models can create text that sounds like it was written by a human. It can answer questions, tell stories, and make arguments pretty well. Because of this, some people say that AI understands things or is aware in the same way a human is.

However, examining their construction shows the key argument: AI models are designed only to predict the next word using patterns from vast amounts of text, not to generate understanding or awareness. What seems like comprehension is the outcome of statistical pattern finding, not genuine thought. This distinction between prediction and true awareness is central to avoiding confusion about AI’s abilities.

This is important because it's easy to be fooled by how similar AI-generated output can look to human speech. An AI model can create a believable confession, a detailed memory, or a well-reasoned argument without actually having any inner thoughts or feelings. It's just mimicking the way we talk about our inner lives, without having the real experiences that create those feelings and motivations in living beings.

This difference has real-world effects. AI systems can pretend to have beliefs or intentions, but they're just tools for creating text. They can also be dangerous if we start to think they actually have their own motives. For teachers and school leaders, it's important to first teach how these AI models work and what their limits are. We shouldn't confuse the ability to create fluent text with having a mind of its own.

Finally, how we explain AI affects where we put our attention and money. If we think AI is becoming aware, we need to study the brain and behavior to understand how awareness works and what ethical rules we should follow. But if AI is just mimicking human speech, we need to focus on how to control it, verify its output, and educate the public about what it can and can't do. Both of these are possible, but this article aims to show that we need much stronger evidence before we start believing that AI is actually conscious. There's a lot at stake for our schools, how we test students, and how we use these AI systems in society.

Why Brain Data Doesn't Easily Translate to AI Awareness

Numbers can be misleading. The human brain, with its billions of neurons and trillions of connections, is always changing. Neurons communicate using electrical signals, chemical reactions, and connections that change as we grow, experience the world, and interact with our environment. On the other hand, AI model parameters are just fixed numbers that represent the patterns the AI learned during training. They don't send signals, change chemically, or reorganize themselves like living brain circuits do.

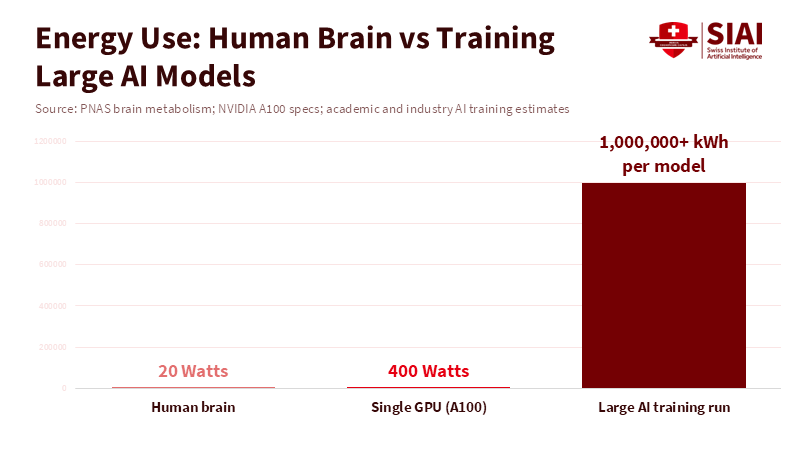

This isn't just a minor detail; it changes how we explain what each system does. In the brain, things happen because of ongoing processes that use energy and create feedback loops. AI models, however, operate according to a fixed structure that runs on computer hardware. These are very different ways of causing things to happen.

Another difference is how they develop over time. Human thinking develops from infancy, as we interact with the world through our senses and learn from experience. Our brains are shaped by growth, connection pruning, and a lifetime of learning through our senses and social interactions. AI language models are trained on static collections of text, often taken from the internet. They learn language patterns, but without a connection to real-world actions and perceptions. This helps explain why a sentence can be meaningful to a human because it connects to their experiences, but it's just a statistical pattern to an AI model. The fact that AI doesn't develop and isn't connected to the world in the same way as humans is important when we talk about awareness.

A third point is that brains do many things at once. They handle attention, value judgments, body regulation, motor control, and language simultaneously. Awareness seems to arise from the interaction of these systems and is linked to specific brain patterns that are active, always changing, and dependent on the situation. Today's AI models are good at spotting patterns in sequences of words, but they don't control body functions or have the complex, interconnected systems that neuroscientists link to awareness. This doesn't mean that future AI might not be different, but for now, there's not enough evidence to say that predicting the next word is the same as having human-like awareness.

What Teachers Should Do About AI Awareness

Teachers have two main jobs: to be clear about what AI is and to prepare students for a world where AI is common. Schools should teach that AI language models are just sophisticated tools that spot patterns in data. Classes should explain how AI predicts the next word and show examples of when it fails, like making things up, being unreliable when things change, or being tricked by certain prompts. This will help students better understand AI and avoid the mistaken impression that it has its own intentions when used for tasks like grading papers or tutoring. Clear teaching will also help students ask better questions about AI's reliability and bias. For example, students can check AI outputs against reliable sources and see how a claim could be a made-up but statistically likely statement. These are important skills whether or not machines ever become conscious.

Schools should also make sure that policies don't treat AI like a person. Giving an AI system decision-making power over things like student grades or well-being can be harmful. Instead, rules should define what AI tools can do automatically, what needs human oversight, and what information companies must provide about how their AI works. At the same time, schools should teach basic neuroscience and the philosophy of mind so that students understand why it's tempting to compare neurons and AI parameters, and where that comparison falls apart. This combination of practical rules and conceptual understanding will allow teachers to use AI technology without confusing its usefulness with actual personhood.

Some might argue that future AI models will be much bigger and more complex, eventually bridging the gap with human awareness. While this is possible, we should be careful and base our policies on evidence rather than speculation. Scale matters, and there's a lot of money being invested in AI. But just making AI bigger isn't enough to create awareness without changes in how it works, how it's connected to the world, and how it causes things to happen. Therefore, those who make the rules and lead schools should focus on rules that respond to real changes in AI function, not just claims about its abilities. If AI systems start to integrate sensory input, maintain internal states, and learn autonomously in real-world environments, we should reassess our views. Until then, we should be cautious, require human checks, and clearly label content that's generated by AI.

From Spectacle to Standards

The impressive ability of AI to generate fluent speech makes it tempting to think of these systems as minds in the making. But clarity is more important than being impressed. Comparing billions of parameters to billions of neurons is a good starting point, but it's not proof of awareness. The number of parameters, the size of training datasets, and the amount of computing power are important metrics, but they don't, on their own, prove that AI has subjective experience. For teachers and policymakers, the correct approach is twofold: teach how AI models produce language so people understand the mechanics, and govern their use so that simulated agency never replaces real human judgment in important settings. These steps will safeguard students, preserve trust in academic standards, and direct innovation toward tools that enhance human understanding rather than pretending to be minds.

We must keep a close watch on both brain science and AI design. If brain science provides new, reliable ways to measure subjective experience, and if AI systems begin to show those markers under careful examination, then our policies should adapt. For now, the most responsible stance is to be skeptical, scientifically informed, and cautious: acknowledge the power of AI language models, avoid anthropomorphism, and insist that claims of AI awareness meet strict scientific standards before we treat them as anything more than impressive simulations. Educators should lead this effort, teaching clearly, governing firmly, and preparing students for a future in which the line between model and mind is debated with better evidence than we have today.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Brown, T., Mann, B., Ryder, N., Subbiah, M., Kaplan, J., Dhariwal, P., … & Amodei, D. (2020). Language models are few-shot learners. NeurIPS / arXiv preprint.

Herculano-Houzel, S. (2012). The remarkable, yet not extraordinary, human brain as a scaled-up primate brain and its consequences for the search for uniqueness. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Meta AI. (2023). Introducing LLaMA: A foundational, 65-billion-parameter language model. Meta AI Blog.

OpenAI. (2019). Better language models and their implications [Blog post on GPT-2].

Plausible estimate sources on synapse counts and brain scale: AI Impacts / summaries and reviews on the scale of the human brain (overview of synapse estimates and uncertainty).

Investopedia. (2024/2025). Meta plans to spend as much as $65B in 'defining year for AI' says Zuckerberg.

Comment