Building-level Energy Optimization: the Cheap, Fast fix Europe Keeps Ignoring

Input

Modified

Building-level energy optimization is the fastest, cheapest path to energy resilience Predictive analytics now enables precise, meter-level energy savings The main barrier is governance and implementation, not technology

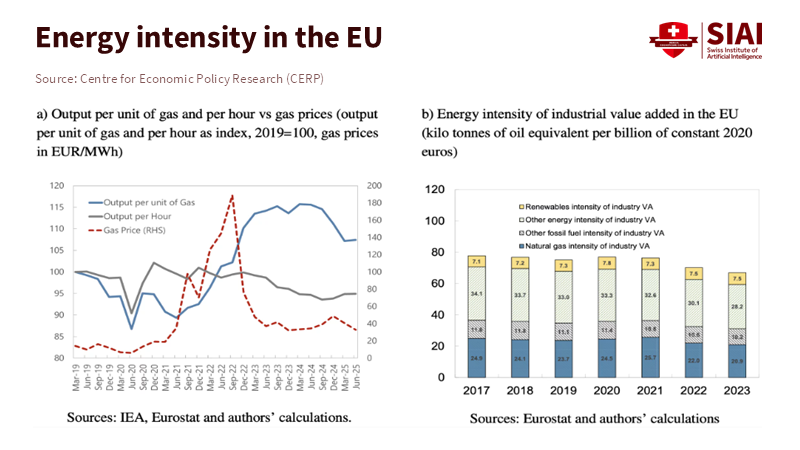

One of the clearest takeaways from the past five years is that buildings across the European Union—homes, offices, and factories—account for roughly 40% of all energy consumption. What's even more interesting is that we can greatly reduce this demand with changes that pay for themselves surprisingly quickly, often in just a few months or years. This means the most cost-effective and rapid ways to lower utility bills, cut emissions, and boost productivity aren't always about building new power plants or pipelines that cross borders. Instead, it's about making better use of the existing electrical systems, controls, and data we already have in place. With recent advances in predictive modeling, we can now forecast energy use at the level of individual buildings and even specific meters. This changes the whole conversation. If businesses and schools can accurately predict their energy needs, they can implement predictable reductions, schedule energy use more intelligently, and make targeted improvements to their facilities. These become practical policy tools, not just interesting ideas. The large energy transition that we've been told will take decades can start paying for itself as soon as next quarter—that is, if policymakers, financial institutions, and building managers start treating energy efficiency as a critical priority, rather than an afterthought.

Moving from Promise to Action: Building-Level Energy savings

Why we present energy-saving strategies makes a significant difference, because the main problem is not that we lack models. Recent academic and real-world work over the past three years has largely closed the knowledge gap. Machine learning, mixed models, and predictors that use all relevant information can now make accurate monthly and hourly predictions of building energy loads, outperforming prior methods. One recent study modeled the monthly electricity and gas consumption of individual buildings in cities. It found that simple information, such as the building's size, number of floors, and construction date, can be used to make accurate predictions. These predictions allow building managers to schedule heating or delay non-essential operations without causing any problems. Similarly, many peer-reviewed studies and applied research since 2023 have shown that neural networks, mixture statistical-physical models, and mixture learning models routinely improve out-of-sample accuracy and reliability in building-level forecasts. So, getting energy savings at individual meters is less of a technical problem. The real challenges concern management, finance, and compliance with rules.

Even the financial world is starting to catch up. Investment experts focused on energy-saving infrastructure are now developing project packages that enable small and medium-sized businesses to make significant improvements to their buildings and control systems. They can do this with minimal upfront capital. New reports and investment plans show how energy-as-a-service deals can turn projected savings into reliable cash flow. This attracts investment from big institutions. This changes how companies see the situation. Leaders have always believed efficiency improvements distract from their core business. It is now an investment. Because science can now provide forecasts at the building level and markets can provide no-recourse funding, the remaining questions concern process: How do we measure the energy used before improvements? How do we make sure those savings are real? How do we move operations to trusting automated controls? And how do we begin test programs across thousands of different sites? These problems can be solved. The question for policymakers is not, Can we predict energy use? The real question is, how do we make those predictions useful, verifiable, and fundable on a large scale?

Turning Predictions into Action: Three Steps for Scaling Up Building-Level Energy Optimization

To begin, we need to establish methods to measure energy use before improvements and create open, verifiable systems that accept probability-based forecasts as valid for performance-based contracts. A predictive model is helpful only if contracts and the rules that govern them use the model's output as the benchmark for payment or compliance. Practically, this means updating current measurement and verification standards to enable forecasts that account for a range of possibilities and levels of certainty. Energy service companies could be paid for expected savings while also sharing some of the risk with the building owner. A cost-effective way to confirm the improvements is to compare two similar groups and assess changes after the improvements. Policymakers should launch pilot programs to standardize these methods across areas. These standards should include basic information about buildings that predictive models already use, such as size, age, and use. This means scaling up depends more on data matching than on installing new sensors.

The second step we must take is to free up investment capital. Instead of making loans on a building-by-building basis, investors should invest in small-site portfolios. Large, institutional investors won’t buy thousands of tiny contracts unless the cash flows are massed and similar. Platforms for energy-as-a-service are transforming the small, individual savings generated by predictive models into investment-grade assets by combining retrofits with operations and maintenance services. A tiny number of partnerships and funds have demonstrated proof of concept. Public financial institutions are beginning to guarantee junior tranches, reducing the cost of securing capital for a series of implementations targeting SMEs and public buildings. This necessitates an operation, baseline data standards, and interoperable metering. The portfolio managers may quickly re-run forecasts, restate exposures, and trigger maintenance. A small investment in data standards and APIs yields an oversized return in deployable finance.

The third thing is that in energy-intensive firms and the public sector, we must shift procurement and operations to incentives. Energy managers are often constrained by procurement rules that prioritize the lowest upfront cost over overall value. And predictive control systems create value streams that are sensitive to operational procedures and unfold over several years. To make sure this happens, it is best to update procurement to public and allocation rules to company capital. This would enable multi-year energy service contracts and create teams focused on reducing energy use and improving average use. Support and training are essential: staff must learn to trust automated schedules, accept occasional false positives, and monitor for model drift. The transition might accelerate as a result of funding for transition teams and by linking a portion of public-sector energy budgets to verified cuts, creating internal demand.

Measuring the Potential Upside: Realistic Estimates and Policy Implications

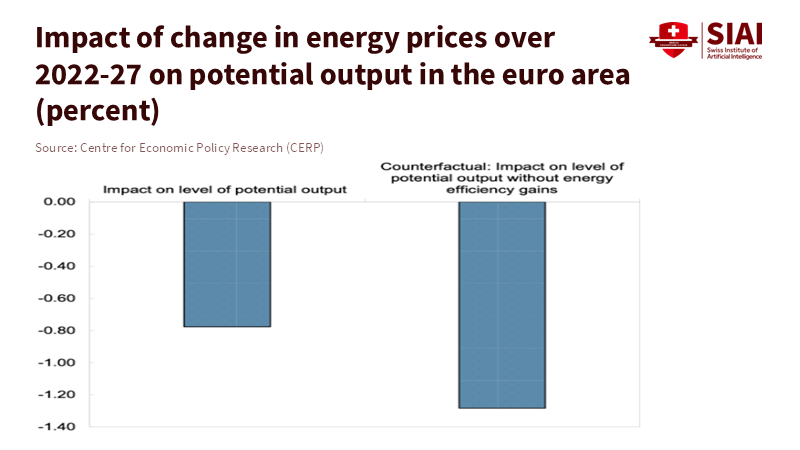

If countries move beyond test programs, how large will the benefits realistically be? Based on careful, well-researched estimates, the macro and micro payoffs would be substantial. Given that buildings account for about 40% of the EU's total energy use, and that building-level optimization could reduce that demand by 10–20% on average where implemented, the near-term reduction in demand would amount to several percentage points of national electricity and gas consumption. That's very important, especially when supplies are tight. Each percentage point of demand that's avoided reduces price sensitivity, lowers import costs, and decreases financial risk. The best government policy would be to see building-level optimization as an alternative to costly supply-side investments. It would provide insurance that reduces demand during peak times.

For businesses, the gains can be even faster and greater. Evidence shows that when businesses use targeted control logic, predictive scheduling, and small physical upgrades, they can reduce their energy bills by double-digit percentages within months. Moreover, productivity often increases because thermal comfort and indoor air quality improve. The implication for schools is clear: they can adopt predictive control systems, lower costs, and reallocate budgets to learning activities that support students and faculty, all while improving overall outcomes. Key metrics managers should consider are not merely average kWh saved but also variance reduction and peak charges avoided. Transaction costs offset can lead to immediate savings.

Addressing Concerns: Backing Up Our Claims with Evidence

A common criticism is that predictive models won't be accurate across different types of buildings. The evidence suggests the opposite: mixed methods combine physical understanding with data-driven learning and are explicitly designed to extend well across buildings and climates. Many studies and reviews report graceful performance degradation and improvements as a result of robust building metadata. Rather than delay for perfection, governments should fund models. Regulators should require reporting errors and transparency.

There is concern that all investments will flow to well-funded firms, potentially leaving low-income households behind. By having targeted public programming, you can prioritize upgrades to affordable housing. This, combined with asset finance, will yield private capital. Combining methods, subsidies, and finance will preserve equity while mobilizing activity.

A third pushback holds that implementation requires sensors and monitoring. However, this overstates the case. Predictive models work with strategically placed and existing sensors. Privacy can be maintained through a combination of dataset anonymization and well-designed contracts. The guidelines here cover data standards and privacy protections, but don’t let hardware adoption slow down.

As noted in the introductory paragraph, buildings account for 40% of our energy consumption. Energy optimization is a fast way to demonstrate resilience, equity, and productivity. We have the tools and documentation to guide us in managing finances. So what is left: policies, methods, underwriting, and reformation. Policy makers and institutional investors should regard building-level upgrades as scalable infrastructure. The return will be immediate and cumulative. We must act, so the savings can be used where they're needed most.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

BuildEvo (2025) BuildEvo: Designing building energy consumption forecasting with LLMs and interpretable heuristics. arXiv preprint.

European Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) (2026) A silver lining to the European energy crisis: Energy efficiency, productivity, and potential output. VoxEU Column.

European Investment Bank (EIB) (2026) EIB teams up with Solas Capital to accelerate energy efficiency gains for businesses across Europe. Luxembourg: EIB.

European Commission (2023) Strategic Energy Technology Plan: Energy efficiency and the EU economy. Brussels: European Commission.

Song, J. (2023) Modeling joint distribution of monthly energy uses in individual urban buildings. MSc Dissertation, Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI).

Solas Capital (2025) Beyond Savings: The Social Impact of Energy Efficiency Investments in Europe. Zurich: Solas Capital.

Yin, Q. (2024) ‘A review of research on building energy consumption prediction models based on artificial neural networks’, Sustainability, 16(17).

Comment