Unshackling the Taboo: How Japan arms exports will redraw Asia’s strategic map

Input

Modified

Japan arms exports end an 80-year taboo and create a major strategic inflection The shift combines legal change, record budgets, and political mandate—money meets law Tokyo must pair exports with strict controls or risk a regional arms spiral

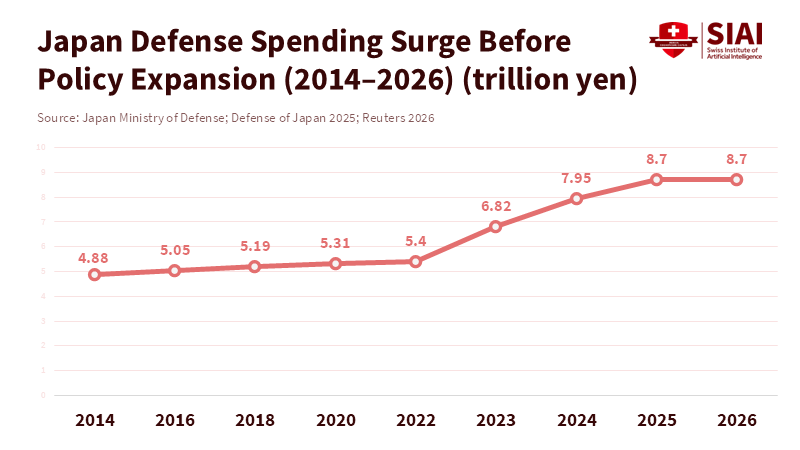

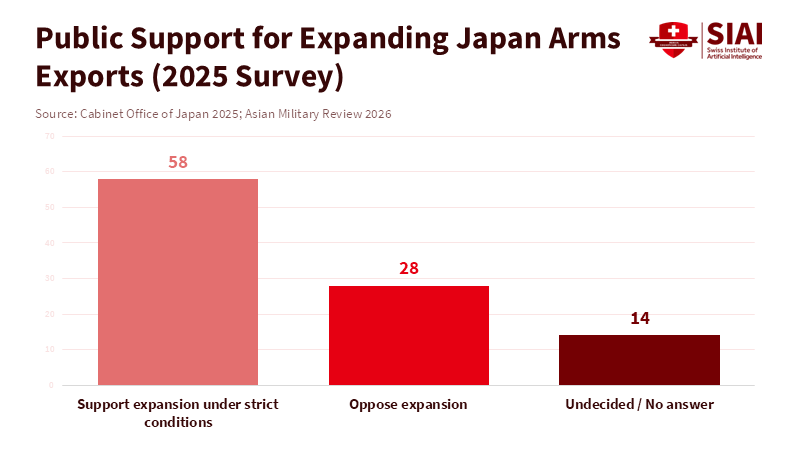

Japan's arms exports are no longer merely hypothetical. Over the last couple of years, Japan has shifted from strictly controlled transfers to a more open approach. The government approved a record-high defense budget, raising total spending to more than 9 trillion yen by 2026. A legal change in late 2023 now lets Japan transfer arms and co-develop weapons under certain conditions. Additionally, a January 2026 survey found that many people support promoting defense equipment exports when specific rules are in place. With money, new laws, and public support, Japan is at a turning point. If Japan decides to allow normal exports of weapons and equipment that can be used for both civilian and military purposes, it will do more than just create business for its factories. It will change how alliances operate, how we think about defense in the East and South China Seas, and how countries such as China, South Korea, Australia, and the United States address their military weaknesses. The challenge isn't only theoretical. It's immediate and affects the whole system. Even small changes to Japan's rules will have big effects on supply chains, command structures, and regional politics. This article argues that Japan's move toward exporting arms is about ending an old way of doing things and starting a new industry. The results will likely be complex and uneven, with major consequences.

Japan's Arms Exports and the New Political Context

The legal and political barriers that kept Japan out of the global arms market have been weakened. The government changed the rules in late 2023 to allow more transfers under certain conditions, as well as joint development of weapons. Since then, legislative and practical measures have facilitated the export of arms on a larger scale. These changes are important because the old no-export policy wasn't just a law. It was an instructive principle that shaped business strategies, workforce skills, and diplomatic approaches for many years. If that principle is broken, everything changes. Politically, the February 2026 election gave the ruling coalition a large majority in the lower house of parliament, giving the government greater authority to translate guidelines into concrete policies. This strong parliamentary support removes a key obstacle: those who oppose these changes can no longer count on narrow legislative margins to block progress. As a result, rules will be issued more quickly, licensing decisions will be made more quickly, and companies and banks will recognize that defense exports are a government priority.

This isn't just happening within Japan. The timing of this political power shift coincides with Japan's alliance calculations. The United States has been encouraging Japan to assume a larger role in defense production so that they can work together more effectively and share the burden. Exports, when coordinated with allies, can strengthen industrial ties and ensure that partners use the same support systems. At the same time, a visibly rearming Japan will be perceived by China as a change in direction. This reaction is understandable. From China's perspective, Japan's sale of weapons—even if they are ostensibly for defense—will create a sense of threat and encourage China to respond with its own military buildup. The key point for experts to remember is that this policy isn't just a single action but a change to the entire system. New laws, money, and authority will produce ripple effects on politics, industry, and diplomacy.

Japan's Arms Exports and Industrial Reality

Allowing exports is one thing, but reliably supplying foreign customers is another. Japan's defense industry was designed to serve a single primary customer: the Self-Defense Forces. That focus resulted in high-quality weapons, but also small production runs and a fragile supply chain of specialized suppliers. Scaling up for export markets requires a different approach: larger production batches, adherence to international standards, and cost-cutting strategies that companies use when they expect repeat orders. The recent increase in the defense budget provides funds, but funds do not automatically translate into export capacity. Companies need long-term procurement contracts, stable orders, and standards that foreign buyers can integrate into their forces. We can expect a transition period where Japan secures a limited number of deals—often for specialized maritime and surveillance systems—while it rebuilds its supplier networks and negotiates offsets.

There are also management issues on the industrial side. Defense exports often require complicated export compliance systems, monitoring of how the weapons are used, and long-term maintenance commitments. Japan's export control system is being revised, but it now needs to be implemented across licensing offices, inspection procedures, and export financing tools. These administrative tasks will determine whether Japan becomes a reliable supplier or merely a supplier in name only. Overall, Japanese companies can compete on quality and system integration, but only if policymakers are patient about scaling up and provide incentives to rebuild the supplier base. The desire to announce quick market success will conflict with the industrial reality: exports will grow, but at a controlled pace unless Japan chooses to provide heavy subsidies and guaranteed orders.

Japan's Arms Exports and Regional Strategic Ripples

If Japan starts selling more advanced weapons abroad, the strategic situation in Northeast and Southeast Asia will change in both predictable and unpredictable ways. Predictably, weaker countries that lack maritime surveillance, patrol boats, or air defense systems may welcome transfers that improve their ability to monitor their waters. These transfers can quickly fill capability gaps and enhance cooperation in response to threats such as trafficking and illegal fishing. Unpredictably, these same flows can trigger strong reactions from major powers. China will not see Japanese exports as neutral; it will view every sale through the lens of the balance of power. This creates two risks: a tit-for-tat situation in which neighboring countries seek their own suppliers, and a hardening of diplomatic relations in which cooperation decreases and crisis management becomes difficult.

The policy response must be clear and carefully thought out. Japan can reduce misunderstandings by prioritizing transfers that provide capabilities that benefit everyone—maritime patrol, search and rescue, and mine clearance—while avoiding weapons designed to project power. Transparency, binding agreements on how weapons will be used, and multilateral notification systems can reduce the risk of escalation. But even the most careful policy can't erase the political messaging of rival countries. For experts and decision-makers, the key point is that arms exports are a signal as much as a transfer of capacity. Signals are interpreted. They influence propaganda, domestic politics, and alliance calculations. Japan must design its export portfolio with both capability and signal control in mind.

Japan's Arms Exports: Policy Design to Limit Downside

Good policy necessitates clear rules and reliable oversight. According to Nippon.com, if Japan proceeds with arms exports, it will establish stricter approval procedures and institutional frameworks intended to ensure more intensive oversight and responsible use of transferred defense equipment. This includes strengthened controls and checks to ensure that arms transfers support security policy objectives, including the preservation of transparency and accountability. weapons. Joint development projects with allies can share costs and create benefits, but they must include clauses that restrict unilateral re-transfer and secure sensitive technology.

Domestic politics will test any plan. Arguments about job creation and industrial revival will be met with objections about pacifism and constitutional issues. The current political majority makes decisive reform easier, yet also increases the moral and reputational costs if the process is rushed or secretive. A better approach unites strength with caution: remove the most damaging restrictions, but pair each action with strict procedural safeguards. This approach lowers the risk of immediate escalation while allowing Japan to rebuild its defense industrial base at a pace that matches its diplomatic capabilities.

Japan's arms exports are more than merely a shift in economic policy. They represent a structural change in how Japan projects influence and organizes power. The 2023 legal revision, the record defense budgets passed between 2024 and 2026, and the recent political mandate all make a new export policy likely. This policy will change alliance logistics, strain industrial supply chains, and force strategic recalculations. The right move for Japan is not to abstain, but to manage the process. It should enact strict controls, prioritize equipment that builds capacity and reduces misperceptions, and embed exports in lasting partnership frameworks. The alternative—rapid export increases without controls—risks fueling arms competition and diplomatic breakdown. Japan now faces a choice: to export in ways that stabilize regional defense cooperation, or to export in ways that accelerate a security spiral. The stakes are high. The opportunity to design a careful path is limited. The consequences of a design mistake for the region and for Japan's identity after the war will endure for many years.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Al Jazeera (2025) Japan gov’t greenlights record $58bn defence budget amid regional tension, 26 December.

AP (2026) Prime Minister Takaichi's party wins a supermajority in Japan's lower house, 2026.

Asian Military Review (2026) Government poll shows public support for defense exports as Tokyo considers easing key restrictions, February.

Defense News (2025) Japan passes record defense budget while still playing catch-up, 16 January.

Japan Ministry of Defense (2025) Defense of Japan 2025, Tokyo: Ministry of Defense.

Ministry of Defense Japan (2023) Implementation Guidelines for the Three Principles on Transfer of Defense Equipment and Technology, Tokyo: Government of Japan.

Nippon.com (2026) Cabinet Office survey shows record high support for strengthening Japan’s Self-Defense Forces, 28 January.

Naval News (2025) Japan approves record defense budget for fiscal year 2026, 30 December.

Reuters (2026) Why Japan’s emboldened PM won’t toy with risks of a weak yen, February.

SIPRI (2024) Trends in International Arms Transfers, 2023, Stockholm: Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

The Guardian (2026) Sanae Takaichi’s conservatives cement power in landslide Japan election win, February.

Xinhua / News agencies (2025) Japan’s defense budget tops record 9 trln yen for fiscal 2026, 26 December.

People’s Daily (2026) Commentary on Japan’s expansion of military exports, 12 February.

Comment