When War Weakens Democracy: Why Conflict Is an Opportunity for Durable Institutional Rollback

Input

Modified

War weakens democracy not by necessity, but by creating incentives for leaders to centralize power The erosion of courts, media, and civil liberties often outlasts the conflict itself Protecting democratic institutions during crisis is a policy choice, not a luxury

In more than 40% of countries, democracy declined from 2019 to 2024. This decline worsens when war is involved. This isn't just a random coincidence. New evidence shows that when armed conflict begins, it often causes democratic institutions to weaken rapidly and to continue weakening for nearly 10 years. This isn't just because war makes things difficult. Instead, war gives leaders an opportunity to consolidate more power. They can centralize authority, reshape or sideline courts, limit public debate, and turn temporary emergency measures into permanent rules. It is important for teachers, college leaders, and policy experts who value a strong civic society to understand this. If war regularly leads to long-term damage to democratic institutions, then protecting democratic standards during and after conflict needs to be a main focus, not something we think about later. This paper discusses the issue from a new perspective: war doesn’t automatically destroy democracy, but it often makes weakening democracy both politically appealing and technically possible. That combination creates a serious risk.

Why war weakens democracy: incentives, timing, and selectivity

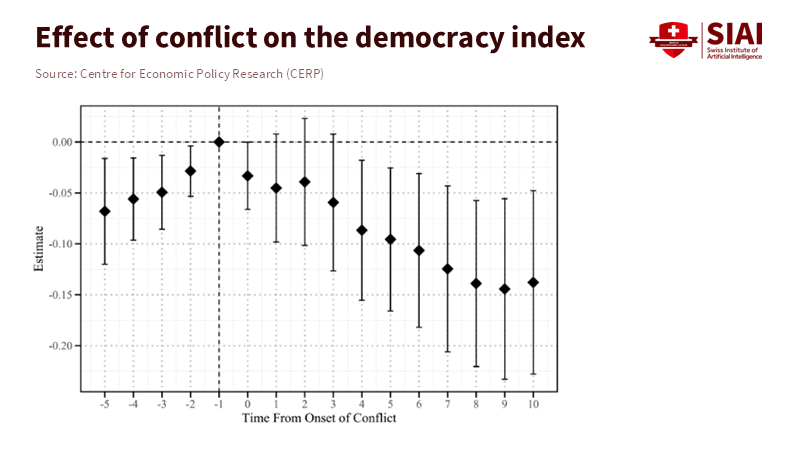

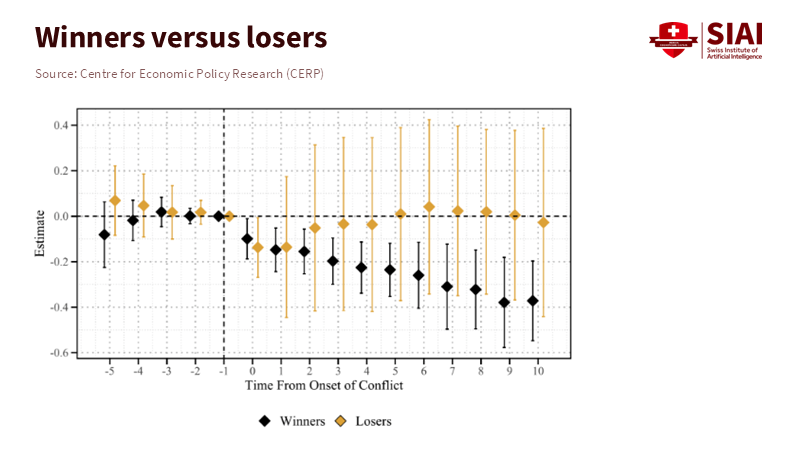

War gives leaders reasons to change the rules, and when they act matters. According to a study by Acemoglu, Robinson, and Torvik, when a government faces conflict, centralization of state authority can lead citizens from diverse backgrounds to unify their demands around public goods rather than narrower interests. This isn't just a theory. Careful research worldwide shows that democratic institutions weaken rapidly after a conflict begins, and this weakening continues for years, even after the fighting ends. The decline is evident in internal conflicts, in wars fought for the first time, and in divided societies characterized by significant ethnic or political differences. These patterns indicate that this isn't merely a standard emergency response. It’s a predictable political process that has lasting effects.

The reasons why war creates these conditions are pretty clear. Leaders gain both the justification and the means to take over authority. They can declare emergencies, use military command structures, and find legal shortcuts. They can bypass parliaments to make decisions faster. Judicial review poses an obstacle because courts may block expedited wartime measures or require officials to comply with rules that slow decision-making. It's hard to maintain media examination and civil society oversight when you're constantly at war. This situation turns short-term emergency measures into standard practice.

Over time, these practices make it easier to take further power. According to Wikipedia, democratic backsliding tends to happen gradually through legal measures that weaken democratic institutions, so what might begin as a temporary move to centralize power during a crisis can turn into a lasting change in how power is distributed—and this helps explain why declines in democracy often persist well after conflicts have ended. Once institutions change, they don’t automatically revert to their previous state.

How the research was done: verifying the pattern

The central claim – that the start of a conflict predicts a multi-year decline in democracy in many cases – is based on comparing countries that went to war with similar countries that did not. These analyses use long-term conflict data (from after 1948) and democracy indicators from specialist evaluations of institutional measures. They show immediate declines in civil liberties, judicial independence, and media freedom, with the decline continuing for several years on average. The research shows that the effect is greater in internal conflicts and smaller in short conflicts, as well as those with external constraints. This isn't a universal rule, but it’s a strong, repeatable conditional effect.

How it happens: censorship, courts, and executive power grabs

Censorship usually comes first. Authoritarian actions often start with limits on reporting and public debate. During wartime, it's easier to justify controlling information and harder to argue against it. States often restrict access to battlefield information, crack down on reporting they deem false, and increase online censorship in the name of national security. Studies of media behavior during wartime – including detailed analysis of language use in the conflicts of 2022–2023 – show significant state intervention in traditional and social media. This reduces the space for civic activity and limits the ways in which people can organize dissent. Once media freedom is weakened, other institutions feel pressure to conform or remain silent.

Courts and legal norms are another pathway. During wartime, governments must decide whether to respect judicial independence or neutralize courts that might challenge emergency measures. Across democracies and mixed systems, we're seeing similar legal strategies: purging or reappointing judges, changing appointment rules, creating special tribunals, and increasing executive influence over prosecutors' offices. These institutional changes are often presented as reforms to improve efficiency or fight corruption, but they predictably reduce legal checks on executive action. Reviews at the European level and comparative audits of judicial independence in recent years trace this backsliding to political events related to security concerns or intense mobilization pressures. The result is a judiciary that’s less willing and less able to act as a check when leaders push the limits of their power.

The third factor is political opportunity: leaders use war to change the rules in ways that help them stay in power. The data shows the inconvenient truth: the move toward autocracy that follows conflict rarely improves wartime performance and often harms it, yet it serves the political goals of those in power. Executives expand emergency powers, change electoral rules, or create legal barriers to the opposition that last beyond the conflict. The political logic is unpleasant but simple: when the focus is on survival, public scrutiny decreases, and institutional inertia allows for gradual rollbacks. This explains why democratic quality declines for years after the fighting stops – the political groups that benefited from the power grab resist reversing it.

What this means for educators, administrators, and decision-makers

Education leaders should make democratic resilience a key organizational goal. Schools and universities aren’t neutral during wartime. They’re places where norms, civic skills, and public debate are shaped. When public space shrinks, learning centers can become places for critical thinking – or they can be used as tools for state messaging. The practical thing to do is simple: protect institutional independence, defend academic freedom, and support safe ways to encourage civic education, even during a crisis. This means strong legal protections for how academic institutions are governed, secure access for researchers to information, and plans to protect independent curricula and student voices when external pressure increases. These steps aren’t just symbolic. They protect the social systems that make democratic recovery possible.

Administrators of public systems – from courts to local services – must build multiple layers of protection. Emergency powers should have clear expiration dates, parliamentary oversight, mandatory reporting, and independent review. When possible, institutions should clearly define the conditions that justify emergency measures and establish institutional tripwires that require approval from multiple branches of government before extending them. Policymakers should prioritize transparent measures: external audits of emergency actions, accessible judicial review, and protected channels for civil society to report issues. These measures reduce the momentum that makes temporary measures permanent. Recent policy assessments in Europe and internationally have shown that clearly defined legal structures help, as explicit procedures reduce the risk that emergency practices will become permanent.

Finally, international groups and funders need to rethink wartime assistance. According to research published by Nuno Garoupa, Virginia Rosales, and Rok Spruk, while humanitarian and security aid is vital for saving lives, increasing democracy and governance aid can also help strengthen the autonomy of courts in recipient countries. Aid conditions and technical assistance should therefore focus on building legal capacity aimed at accountability, supporting independent media, and funding judicial programs to reinforce institutional checks. Practical steps include funding independent court reporting, supporting civil society legal clinics, and making technical and budgetary support contingent on the protection of basic institutional safeguards. The goal is not to restrict legitimate wartime action, but to change the political forces: make moves that preserve democracy both possible and helpful during times of crisis.

If war regularly creates conditions that favor institutional rollback, the right approach isn’t to wait for peace and hope things return to normal. Instead, we need to build safeguarding structures now: legal sunset clauses, transparent oversight, funding for media independence, and clear protections for educational independence. These combined measures make it harder for temporary emergency powers to become entrenched as long-term power grabs. For educators, administrators, and policymakers, the challenge is immediate and practical. Make democratic resilience a part of crisis planning. Incorporate safeguards into the law. Fund independent civic institutions. Train leaders to recognize and resist the political temptations that war creates. If we don’t, the familiar pattern after conflicts will repeat: fighting ends, but democratic quality remains weakened. We can avoid this by treating democracy as a key priority during war rather than treating it as unimportant.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Benmelech, E. and Monteiro, J., 2026. War and Democratic Backsliding. NBER Working Paper No. 34734. National Bureau of Economic Research.

European Parliament Research Service (EPRS), 2024. Courts Amid Democratic Backsliding: Rule of Law and Judicial Independence in the EU. Brussels: European Parliament.

International IDEA, 2024. The Global State of Democracy 2024: Strengthening the Legitimacy of Elections in a Time of Radical Uncertainty. Stockholm: International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance.

Kant, I., 1795. Perpetual Peace: A Philosophical Sketch. Königsberg: Friedrich Nicolovius.

Semenov, A. and Alyukov, M., 2023. Wartime Media Monitor (WarMM-2022): Media and Online Communication During Armed Conflict. Conference paper.

V-Dem Institute, 2024. Democracy Report 2024: Democracy Winning and Losing at the Ballot. Gothenburg: University of Gothenburg.

Verfassungsblog, 2022. Democracy under Total War. Berlin: Verfassungsblog.

Comment