When Cheap Becomes Contagious: China’s Deflation Spillover and the New Financial Faultline

Input

Modified

China’s domestic deflation is no longer contained; it now reshapes global prices, profits, and financial risk Industrial subsidies extend price pressure, turning a trade shock into a systemic financial spillover Global policy must adapt quickly to manage a deflationary force emanating from the world’s manufacturing center

China's declining factory prices aren't just a local issue anymore; they're impacting the whole world. For a substantial portion of the last three years, Chinese manufacturers' prices have been declining. This is occurring even though China accounts for a substantial share of global manufacturing. This combination – consistently low factory prices and China's massive manufacturing output, boosted by government subsidies – means that price issues in China are now affecting prices, profits, and investment risks everywhere. When a country that accounts for about 29% of the world's manufactured goods experiences ongoing price declines, the impact isn't just cheaper goods for consumers and businesses. It also messes with company finances, commodity markets, currency values, and asset prices. This creates a new kind of global financial vulnerability, which we can call the China deflation spillover. It's new and important because it combines trade-related price changes with financial volatility. Also, our current policies have been designed for rising prices, not falling ones.

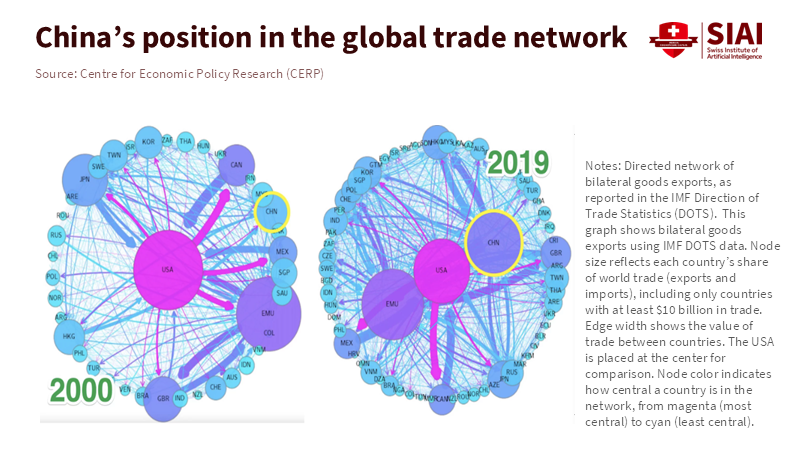

China at the center of global price transmission

This price decline in China started after 2022. The most obvious sign is the drop in factory prices. These prices have been falling for years across many different manufacturing areas. This is significant because China is a major hub for global goods production. Even conservative estimates suggest that Chinese manufacturing accounts for around 25–30% of the world's total. Plus, China is the top exporter of goods. When Chinese factory prices fall, the immediate result is cheaper goods for importers.

Price and demand shocks originating in China now propagate systemically across the network.

But that's just the beginning. Lower export prices also reduce earnings for manufacturers outside of China who sell similar products. It squeezes profits for international suppliers involved in the Chinese market. It shifts the balance of trade in favor of commodity producers, who are seeing less demand from Chinese manufacturers. The overall result is a revision of earnings expectations throughout various industries and regions. For countries closely tied to supply chains reliant on Chinese products, upward pressure on goods prices can erode companies' profits, thereby lowering stock values and increasing the risk of corporate debt. Falling prices at Chinese factories translate into a financial shock that spreads through profit expectations, corporate values, and creditworthiness, well before it affects consumer prices in other countries.

This situation is different from how the U.S. usually affects the world financially. U.S. policy mainly spreads through interest rates and global asset values. China's price influence operates through trade, industrial trends, and the distribution of global supply. It's not that monetary policy doesn't matter; it's just that the way it works is different. Price drops in China reduce global demand for commodities, change commercial balances, and cause currency fluctuations that impact foreign asset prices. When China adds large, targeted industrial subsidies – especially for industries that use a lot of capital and energy – the price situation becomes even more complicated.

Subsidies disrupt the natural process by which companies exit unprofitable markets. They keep production capacity high and maintain downward pressure on prices. The combined result is a lasting, export-driven pressure that global markets have to deal with. This means the global financial system faces a double problem: persistent downward pressure on the prices of traded goods and uneven financial risks as businesses and investors begin to factor in lower future earnings.

Subsidies, excess capacity, and persistent deflation

Government support is important because it influences how companies in China decide whether to invest or close. This affects how long and how deeply deflation spreads. Over the last decade, there's been a noticeable increase in subsidies – both direct and indirect – aimed at important manufacturing sectors, green energy supply chains, and advanced technology goods. Subsidies alter incentives, keeping struggling producers afloat, encouraging expansion in specific industries, and slowing adjustments that would otherwise increase costs and keep prices steady. In a global market in which China is a major manufacturer, this persistent support creates persistent price competition. The policy implication is clear: subsidies increase the China deflation spillover by preventing domestic prices from rebounding, thereby reducing the external shock.

Here's a simple example: imagine China provides 30% of the world's manufactured widgets. Without subsidies, a 2% drop in factory prices would be temporary and reverse within a year as less efficient producers close. But if subsidies keep these struggling firms alive for an extra two or three years, the excess supply increases by roughly 6–8%. This extra supply, which modifies global markets, lowers the global price of widgets by a similar amount, affecting profit margins and company valuations for competitors in other countries. These numbers are just an illustration, but they're based on the growth in subsidies and the observed drop in factory prices. Subsidies extend the period of price pressure, which magnifies financial spillovers that would otherwise be short-lived.

This situation explains why we're seeing constant pressure on global industrial prices, even when consumer inflation is rising in other areas. Consumer prices are slow to change and often driven by services, where China's direct influence is weaker. However, the financial system focuses on corporate earnings, tradeable goods prices, and commodity demand – all areas where China has a big impact. The policy response inside China – partial fiscal boosts, targeted credit, and ongoing industrial incentives – has consistently chosen immediate benefits over structural changes to fix weak domestic demand. This keeps China's external price signal pointing downward, and foreign markets have become used to pricing in a China-related discount in certain industries. These discounts are now manifesting as greater stock market volatility in supplier nations, stricter lending standards for affected industries, and ongoing scrutiny of capital-intensive sectors.

From trade shock to financial contagion

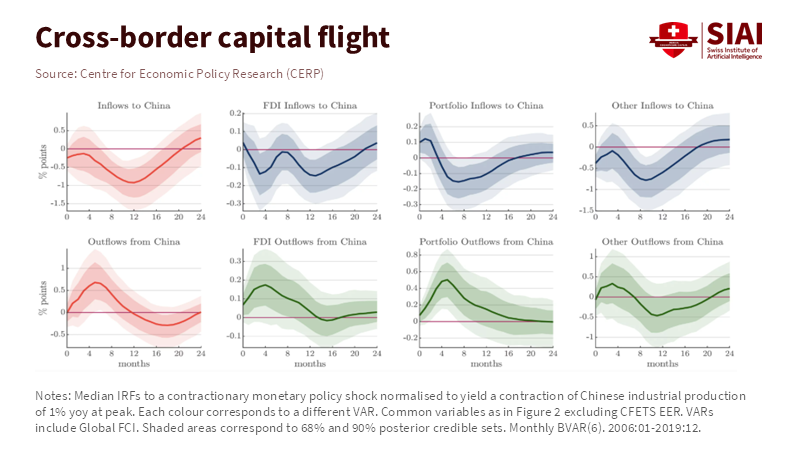

The China deflation spillover starts with trade and commodity prices and then moves into finance. There are several channels for this, and they're becoming more obvious. Companies that rely on demand from China are seeing their earnings downgraded, which reduces their stock market value and increases their corporate bond spreads. Banks with significant exposure to these companies face a higher risk of bad loans, raising concerns about the stability of economic systems in countries with close trade ties. At the same time, China's deflationary pressure reduces global demand for commodities, which puts pressure on producer countries and their government bond spreads. Capital flows react: when profit expectations are revised downward, investors pull out of riskier assets, which influences currency moves and yield differences that can spread into funding markets. Recent research shows that economic disturbances coming from China – whether in the form of monetary easing, credit changes, or demand collapses – are now causing noticeable shifts in global commodity prices, regional bond spreads, and stock indices. These studies show that China's economic disturbances have larger effects compared to shocks from other large emerging economies.

Financial transmission reinforces trade spillovers, amplifying global volatility.

One important and often overlooked aspect is cross-border balance sheet exposure. Many international firms and banks have significant exposure to Chinese production and demand through supply chains, receivables, and inventory financing. When Chinese factory prices fall, and inventories build up, the speed of accounts receivable and inventories slows down, tying up working capital and putting pressure on short-term funding markets. The immediate reaction can be widespread: increased use of credit lines, higher demand for short-term cash, and mark-to-market losses on corporate debt. For regional banks and non-bank financial institutions, these situations increase the risk of not being able to refinance their debts. In 2023–25, changes in Chinese factory output and factory prices correlated with higher volatility in certain regional stock markets and with widening credit spreads in economies that export commodities. This correlation doesn't prove that one causes the other, but it corresponds to structural channels – trade exposure, commodity demand, and balance sheet connections – that could plausibly transmit the shock. Policymakers who focus only on consumer prices are missing the deeper, slower-moving trends that threaten financial soundness outside China.

Policy responses for a deflationary global shock

If China's domestic deflation can turn into international financial stress, then we need to review our policy approach. First, financial regulators in countries with strong trade ties should include trade-related deflation scenarios in their stress tests. This means simulating sustained downward pressure on tradable goods prices, combined with continued production capacity in exporting nations supported by subsidies. Banks and other lenders should assess how well their balance sheets can cope with increased draws on receivables and slower inventory turnover, which can restrict short-term funding. Second, trade and competition policies need to do more than manage market access. They need to consider the financial effects of subsidies that compress prices. Tariffs and quotas are not precise tools and can lead to fragmentation, but targeted, rules-based solutions – clear subsidy notification, enforceable rules, and dispute resolution processes – are needed to fairly revalue risk and avoid hasty, destabilizing measures.

Third, international coordination is important because unilateral actions, such as tightening monetary policy or imposing tariffs, are likely to backfire by reducing global demand. If China is the center of global manufacturing, a disorganized reaction by its trading partners could worsen global weakness. This means central banks and finance ministries should broaden the range of scenarios in their joint modeling and consider preemptively providing financial support to sectors at risk from price shocks linked to China. Lastly, China's domestic policy affects the rest of the world. If China favors subsidies that maintain production capacity over reforms that increase household income and spending, global price weakness will continue. On the other hand, credible steps toward rebalancing – strengthening social safety nets, reducing reliance on investment-led growth, and managing targeted industrial support within a narrow timeframe – would accelerate price normalization and reduce global financial spillovers.

Some may argue that cheap imports benefit consumers and that markets should adjust without policy intervention. There's some truth to that – lower consumer prices do increase real incomes. But the distribution and timing of these effects matter. Short-term consumer gains can hide long-term disinvestment and job losses in trading partners. Financial stress can emerge in areas not protected by nominal consumption gains. Others might argue that China's size makes its policies a domestic matter. Yet, economic interconnectedness means domestic choices have international consequences. The right approach harmonizes respect for national sovereignty with cooperative schemes to manage systemic spillovers.

China's role as the center of global manufacturing makes its domestic price path a global issue. Constant weakness in factory prices, amplified by industrial subsidies, has evolved from a trade issue into a financial one. Lower margins, strain on balance sheets, portfolio reallocations, and higher volatility abroad. Accepting the China deflation spillover is not about protectionism. It's about responsible risk management and international cooperation. For regulators, the task is practical: expand stress tests to include trade-related deflation scenarios, map corporate and banking exposures to Chinese production chains, and coordinate financial support and regulatory responses across borders. For trade and fiscal policymakers, the task is structural: rebalance incentives so that subsidy policy doesn't permanently distort global prices. If we do this, we'll not only reduce the risk of international financial contagion but also restore clearer price signals for businesses and markets. The opening statistic still matters: when one country provides nearly a third of global manufacturing output, its price dynamics are no longer domestic – they're systemic. Naming the China deflation spillover enables us to address it. The policy test ahead is whether our institutions can understand the situation and adapt before price weakness becomes a wider financial vulnerability.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Abdel-Latif, H. (2025) Spillovers from large emerging economies. IMF Working Paper. International Monetary Fund.

BIS (2024) Global liquidity: drivers and spillovers. Annual Economic Report. Bank for International Settlements.

Capital Economics (2026) Deflation at home, disruption abroad: China’s growth model is a lose-lose. Capital Economics Research Note.

IMF (2024) World economic outlook: navigating global divergences. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

IMF (2025) Global financial stability report: financial shocks and cross-border transmission. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund.

Miranda-Agrippino, S. and Rey, H. (2020) ‘U.S. monetary policy and the global financial cycle’, Review of Economic Studies, 87(6), pp. 2754–2776.

OECD (2025) Industrial subsidies and global market distortions. Paris: Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development.

Rotunno, L. and Ruta, M. (2024) Trade and subsidy spillovers in global value chains. IMF Working Paper. International Monetary Fund.

The Diplomat (2025) Unlike Japan’s lost decade, China’s deflation risk is going global. The Diplomat Magazine.

World Bank (2025) China economic update: navigating deflationary pressures. Washington, DC: World Bank.

Zhou, C., Hoffmann, M. and Straub, L. (2023) ‘Mapping the contours of Chinese policy transmission at home and abroad’, VoxEU / CEPR Policy Portal.

Comment