The Impossible Orbit: Why orbital AI satellites are a coordination nightmare

Input

Modified

A million satellites would overwhelm orbital coordination long before technical limits are reached Collision risk, debris, and governance failures scale faster than engineering solutions Without strict global control, orbital AI becomes a systemic liability, not progress

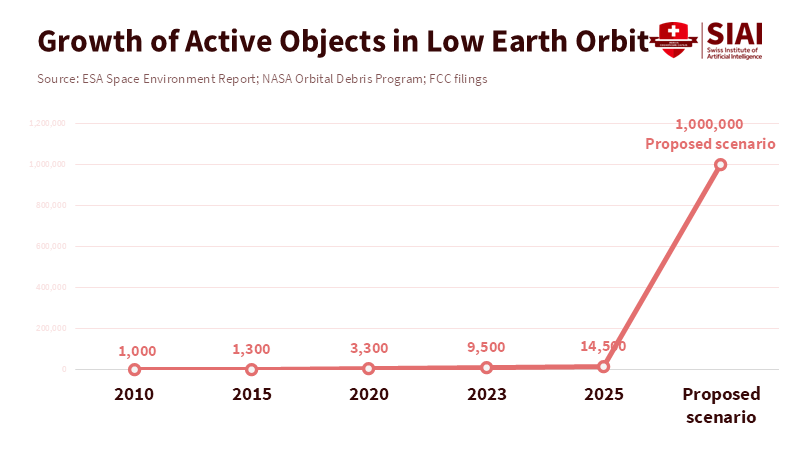

Elon Musk's idea of launching a million AI satellites brings up a serious issue. Right now, there are already about 14,000 to 15,000 working satellites and around 35,000 trackable objects orbiting Earth. Adding a million more would massively increase the amount of traffic in space, turning normal operations into a constant emergency. These AI satellites aren't just a new way to do computing; they also create a major risk. The chances of collisions, the amount of fuel needed, and the creation of space junk would all skyrocket, affecting everyone who operates in space. It's not enough to just look at the cost of each satellite or the potential for solar power. We have to remember that space is unique because of the high speeds of collisions, the difficulty of monitoring everything, and the huge costs associated with even small failure rates at this scale.

Too Many Satellites: The Risks of Density and Debris

The first big problem is the limited space in low Earth orbit (LEO), which is about 200 to 2,000 kilometers above the Earth. This area is already crowded with satellites in specific orbits. There are thousands of active satellites and tens of thousands of cataloged objects bigger than 10 centimeters. The chance of collisions doesn't just increase as you add more satellites; it increases much faster. That's because each new object increases the number of possible close encounters with other objects. When there are few satellites, these situations are rare and can be handled. But when there are many satellites, they become constant and create a continuous burden. If you want to put AI satellites in orbit, you have to be very careful. To stay safe, operators must be extra cautious when executing maneuvers, carry more fuel, and avoid risky experiments. This defeats the purpose of using cheap, mass-produced satellites, turning a potential cost-saving into a situation where caution is the priority.

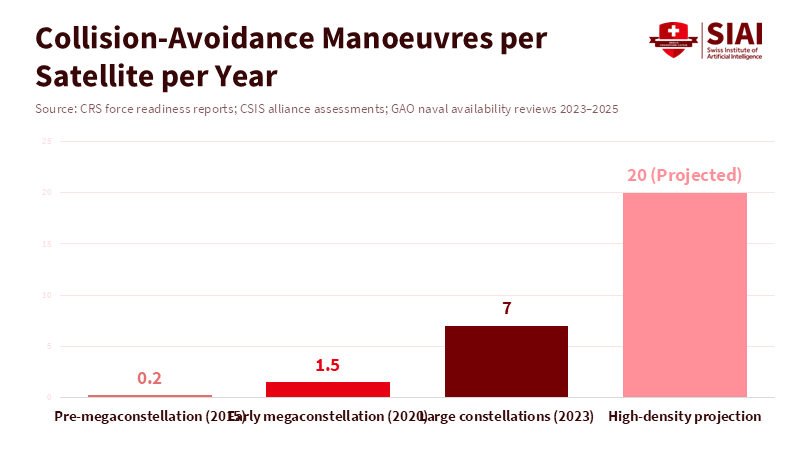

We're already seeing this happen. Reports indicate that large groups of satellites are undertaking avoidance actions much more frequently than they used to. These maneuvers consume fuel, which shortens the satellites' lifespans and necessitates earlier replacement. If avoidance actions become frequent, replacement launches must occur more often to maintain a stable number of satellites. Each launch adds risk and cost, increases pollution, and creates scheduling problems for everyone. So, a plan that assumes it won't cost much to coordinate everything is wrong. The cost of maneuvering, tracking, and replacing satellites increases with the number of satellites, quickly offsetting any savings from mass production.

Space debris renders these numbers a serious hazard. Any collision in orbit will break the hardware into thousands of pieces. Many of these pieces will be too small to track but still big enough to damage or destroy other satellites. Models show that increasing the number of objects in orbit increases the likelihood of collisions, triggering a chain reaction known as cascading fragmentation, or Kessler syndrome. To prevent this, you need highly reliable satellites, a means of removing debris on a large scale, or strict limits on the number of satellites. These options are expensive and technically difficult. In short, the physics of space doesn't scale well. A million satellites isn't just more; it's a completely different level of risk.

Satellite Failures, Fuel Costs, and Surveillance Issues

Building one AI satellite is hard enough, but building a million makes the whole system very fragile. Electronics in LEO must contend with radiation, sudden malfunctions, temperature changes, and impacts from tiny meteoroids. Protecting against these things adds weight and cost. Cooling systems for powerful AI processors in space need surface area and specific orientations, which interfere with maneuverability and communication links. The bottom line is that making each satellite strong increases its weight and reduces the number you can launch at once. Making each satellite simple increases the chances of failure. The number of satellites expected to fail is the product of the probability of failure and the number of satellites. So, even if the chance of each satellite failing is small, you'll still have a lot of failures when you have hundreds of thousands of satellites.

Logistics are another bottleneck. You can increase the number of launches, but launch windows, safety regulations, approvals, and supply chains aren't unlimited. If you launch 100 satellites per launch, you'll need about 10,000 launches to deploy a million satellites. Even if you launch 1,000 per launch, you'll still need about 1,000 launches. Either way, you'll need a long-term global launch program that spans years, along with a reliable service network for communication, tracking, and network access on Earth. Ground infrastructure is a frequently overlooked cost. While using optical links between satellites can reduce some of the burden, you still need reliable downlink infrastructure, spectrum coordination, and regulatory compliance. In reality, the ground network and launch frequency are just as important as each satellite's cost when determining whether the project is feasible.

Monitoring and sharing information are essential for avoiding collisions. Collision avoidance only works if everyone sees the same space and agrees on when to take action. If companies use their own tracking methods, they create blind spots for others and force them to be more careful. Open, shared data would reduce unnecessary maneuvers and improve safety, but it's politically sensitive. It requires trust between competitors and countries and elicits concerns about confidentiality and national security. Without a trusted organization to collect, standardize, and check tracking data, the default approach will be precautionary. This means more maneuvers, faster fuel consumption, and more regular replacements and launches. This is how poor information management turns an engineering difficulty into a systemic crisis.

Note: When reports provide ranges instead of single numbers, I've used reasonable averages and estimates. Deployment numbers (e.g., required launches) are presented as ranges to highlight potential bottlenecks. Information about maneuver counts and tracked objects comes from regulatory filings, reports, and independent tracking inventories to avoid exaggerating precision. The aim is to use the data to support the argument without making the numbers seem like definite predictions.

How to Manage AI Satellites Responsibly

If AI satellites are to become a reality, responsible management must be the priority. This starts with conditional authorization, not just one-time permits. Regulators should set limits on the number of satellites each operator may operate in each orbit, require short de-orbit times for satellites that are no longer operational, and require that satellites have sufficient fuel reserved for collision avoidance. These are rules based on outcomes that don't favor any particular technology but do limit risky deployments. They force operators to take responsibility for the risks they create.

The ability to enforce these rules is essential. Reliable data, independent tracking, and real penalties are needed to change people's actions. Insurance can help, but only if policies and premiums reflect the real risks. Otherwise, insurers won't be able to accurately price the probability of a cascade effect. Public investment can help where private markets don't, such as in shared tracking networks, open data platforms, and research regarding debris removal. But public investment must be tied to rules that prevent people from taking advantage of the system.

International cooperation is also crucial. Space is a shared resource, so what one country or company does affects everyone else. Agreements should define quick responses to possible collisions, require transparent notices before launches, and set rules for who has priority in avoidance situations. Developing and testing these agreements now reduces the chance that a failure could result in a cascade effect. The cheapest way to keep space safe isn't just better hardware; it's better rules, better information sharing, and reliable enforcement.

Taking a long-term view is important. Small fixes can't replace overall controls. Improvements in shielding, propulsion, and onboard systems are helpful, but they're not enough. Without limits, monitoring, and shared traffic management, deploying a million satellites could turn LEO into a dangerous area that increases costs and reduces capabilities for everyone.

In conclusion, adding a million new satellites to an already crowded orbital environment isn't just a small technical problem; it's a major decision with social, economic, and safety implications. AI satellites could provide significant computing power and new services, but only if their deployment is governed by strict regulations, reliable monitoring, shared awareness, and credible enforcement. Regulators should treat deployment permits as conditional approvals based on verifiable milestones. The industry should accept binding standards as the cost of accessing space on a large scale. Without these things, we're relying on perfect behavior and no solar storms to keep space usable, which is a dangerous gamble with a shared global resource. We need to act responsibly now.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

European Space Agency (2024) ESA Space Environment Report 2024. ESA.

Federal Communications Commission (2024) FCC fast-tracks SpaceX’s plan for 1 million satellites—and wants your thoughts. PCMag.

Gibney, E. (2026) SpaceX plans to launch one million satellites to power orbital AI data. Scientific American.

NASA Orbital Debris Program Office (2025) Orbital Debris Quarterly News, Vol. 29, Issue 3. NASA.

Sharwood, S. (2026) FCC opens Musk’s 1M-satellite data center plan for public comment. The Register.

Space.com (2024) Starlink satellites made tens of thousands of collision-avoidance manoeuvres — what that means for space safety. Space.com.

Comment