Wiping or Fighting? Why the China economic footprint is now the battlefield — and what education must do about it

Input

Modified

This is no longer a race to catch up, but a push to reduce strategic dependence on China Supply chains and education systems are now instruments of geopolitical power Resilience will depend on how quickly institutions adapt skills, policy, and procurement

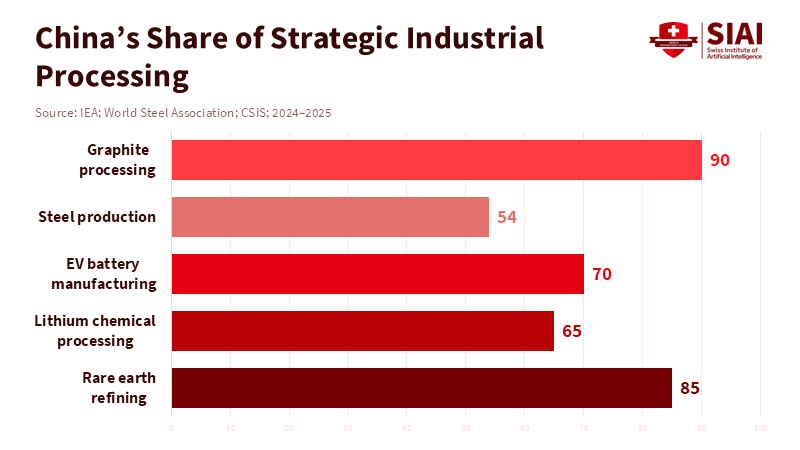

China’s control over a handful of industries is not an abstract risk; it is a measurable chokehold. Today, one supplier — China — refines roughly 80–95% of key rare-earth and battery-processing inputs that support everything from electric cars to guided munitions, while Chinese firms produce more than half of global steel and roughly two-thirds of the world’s electric-vehicle batteries. That concentration turns trade policy into strategic policy. If Washington and its allies truly mean to “push back,” we need to stop calling this a race to “catch up.” This is a suite of deliberate measures to shrink, reroute, or neutralize China's economic reach—from tariffs and allied mineral blocs to industrial countermeasures. The question for teachers and policymakers is not rhetorical; it is: how do we retool our systems so that curricula, research funding, procurement, and workforce pipelines reflect a context in which supply chains are strategic and contested?

China's economic role: reframing the debate from competition to contest

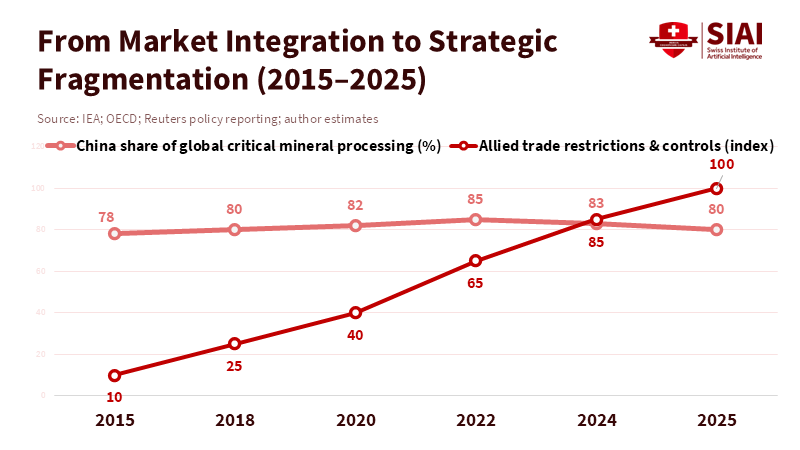

The usual frame treats U.S.–China policy as a race in which America must “catch up” to an industrial leader. That frame assumes benign competition: better technology, more investment, faster adoption. However, recent policy moves indicate a different logic—one of containment through disruption. Rather than merely accelerating domestic capacity, the United States and partner governments are explicitly seeking to erode the structural levers that have given China dominant market positions: concentrated processing, subsidized excess capacity, and integrated export networks. Calling this “fighting” or “wiping out” is blunt. Yet the language matters because it redirects policy: from domestic subsidies and innovation prizes to coordinated supply-chain reconfiguration, trade pacts for critical minerals, and targeted tariff diplomacy. Reframing the moment this way makes clear that the policy toolset must be wider than R&D and venture funding; it must include industrial diplomacy, shared stockpiles, and education systems designed to prepare workers and institutions for a geopolitical economy.

This reconsideration matters now because the vulnerabilities are concrete and time-sensitive. Independent energy and industrial analyses show that a small number of refining hubs control the lion’s share of processing for cobalt, graphite, and rare earths, while Chinese firms dominate EV battery and parts manufacturing. Those facts make supply chains brittle: a policy shock, export restriction, or sustained subsidy war can quickly shift markets and prices, with real effects on manufacturing, research timelines, and administrative budgets. If the goal is to reduce strategic dependence, governments cannot wait for market corrections; they must treat education and workforce policy as instruments of national resilience. That requires rethinking what vocational programs teach, how universities align engineering research with supply diversification, and how procurement decisions incentivize the use of alternative sources.

China's economic effect: the industrial shock — subsidies, oversupply, and the price of cheap goods

For two decades, many Western firms welcomed low-priced inputs and abundant finished goods. That bargain had a cost: it concealed the subsidy-driven expansion behind the low prices. Steel and chemical markets offer a clear example. Global sector reports indicate that state-supported capacity and export surges created long-term oversupply, depressed local prices, and cyclical dislocations that hollowed out competitors’ capital bases. The result is not only fewer firms in competitor countries but also the loss of specialized industrial know-how that cannot be rebuilt overnight. When a national champion undercuts global rivals through prices that do not reflect full production costs, the downstream effect is both economic and pedagogical: local training programs shrink, apprenticeship slots vanish, and university–industry partnerships wither.

The policy response from the United States in recent years has included steep tariffs, reciprocal duties, and negotiation of tariff rollbacks only after strong pressure and market dislocations. Tariffs aim to raise the cost of dependency and to buy time for domestic capacity-building. But tariffs come with trade-offs: consumers and some manufacturers pay higher prices in the short term, and front-loading of imports can distort data and policy timing. Still, the point is strategic. If a large exporting power can reshape global markets with subsidy-backed oversupply, then allies must either replicate costly industries or erect barriers and cooperative systems that limit that power. That is exactly what recent allied moves on tariffs, negotiated tariff reductions, and industrial diplomacy seek to do: constrain the net effect of price-driven dominance while creating space — politically and economically — for alternative suppliers and for investment in skills and industrial ecosystems.

China's economic reach: rare earths, critical minerals, and the allied counterpunch

Rare earths and other critical minerals are the clearest illustration of leverage. For many critical inputs, China historically has owned most of the refining and magnet manufacturing, creating a chokepoint where raw-material diversity meant little unless refining diversity matched it. That structural imbalance incentivizes policies that go beyond tariffs and target the supply chain’s weak link: processing and value-added manufacturing. The last eighteen months have seen explicit policy responses: international discussions to create preferential trade arrangements, coordinated stockpiles, and proposals for price floors to make non-China extraction financially viable. Those are not market nudges; they are industrial strategy in plain sight.

The consequences for practice are immediate. A government or university evaluating procurement can no longer treat “lowest bid” as an unconstrained metric. Procurement becomes a tool of resilience, with ESG and geographic diversification weighted equally alongside price. For educators, that changes the demand signal. Engineering programs should teach materials processing beyond lab-scale extraction. Business schools must add supply-chain geopolitics to logistics and procurement courses. Community colleges need to expand short-cycle training in minerals processing, battery assembly, and remanufacturing. These are not abstract curriculum tweaks. They are the human-capital side of an allied strategy aimed at blunting a single-country chokehold on inputs that power modern defense systems, green technologies, and export industries.

China's economic role: what policymakers, administrators, and educators have to do next

Treat the next five years as a policy window. First, policymaking: coordinate with allies to underwrite the riskier stage of supply-chain diversification — refining and secondary processing — through joint guarantees, targeted public investment, and shared stockpiles. The objective is not to replace China overnight; it is to create credible alternatives and remove monopoly rents arising from narrow supply chains. Second, procurement and administrative practice must evolve. Public-sector purchasing can be used to seed demand for non-China inputs, and conditional contracts can build market confidence among private investors. Third, education and training must be intentionally aligned with these planned objectives. That means funding certificate programs in mineral processing, supporting university–industry consortia for alternative magnet and battery chemistries, and embedding geopolitics in business and engineering curricula so graduates understand both technical restrictions and national-security implications.

Anticipating the main critiques strengthens this program. Critics will say that these moves risk protectionism or raise consumer prices. They are correct that short-term costs will rise; tariffs and strategic investments are not free. But the alternative is a longer-term dependency that leaves economies exposed to supply shocks, export restrictions, or strategic coercion. Another critique is that industrial policy is inefficient. Evidence from coordinated allied initiatives suggests that when governments combine demand signals with transparent, time-bound support — rather than open-ended subsidies — they mobilize private capital and accelerate independent capacity with less fiscal drag. Finally, some will argue that diversification cannot be done at scale quickly enough. That too is correct; hence the need to structure policy as a staged campaign: immediate resilience measures (stockpiles, procurement), medium-term capacity building (refining and recycling), and long-term industrial ecosystems (education, R&D, and regulatory coordination).

From analysis to assignment

If we accept that the current policy thrust is not simply a race to catch up but a vigorous campaign to reduce China's economic role, then the policy problem becomes clearer and more urgent. We are asking educational systems to do a different job: not simply to supply more STEM graduates, but to supply the right skills at the right scale and the right institutional partnerships to support tactical supply diversification. That requires explicit mission alignment across ministries, funders, and campus leaders. It requires investing in short-cycle credentials, expanding applied research on alternative chemistries and processing, and retooling procurement to de-risk new suppliers. The opening statistic — that a handful of processors control the supply of the minerals critical to modern industry — should end debate and start planning. Governments must now treat curricula, funding, and procurement as levers of national resilience. Do that, and the “battle” over footprints becomes less about confrontation and more about durability: durable supply chains, durable jobs, and durable institutions that can weather geopolitical shifts without sacrificing growth or the educational mission.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

International Energy Agency. Global Critical Minerals Outlook 2025 (Executive Summary). 2025.

International Energy Agency. Global EV Outlook 2024: Trends in electric cars. 2024.

OECD. A level playing field is needed for a brighter outlook in the global steel industry: OECD Steel Outlook 2025. 2025.

Reuters. “US proposes critical minerals trade bloc aimed at weakening China’s grip on critical minerals.” Feb 4, 2026.

Reuters. “Sustainable Switch: US and EU stockpile critical minerals.” Feb 6, 2026.

CSIS. “The Consequences of China’s New Rare Earths Export Restrictions.” 2025.

ITIF. “How Innovative Is China in the Electric Vehicle and Battery Industries?” 2024.

Tax Foundation. “Trump Tariffs: The Economic Impact of the Trump Trade War.” 2026 (policy analysis).

World Steel Association. World Steel in Figures 2024. 2024.

Steel Forum / GFSEC. “Global excess capacity and employment in steel.” Report (PDF). 2025.

China Briefing. “China’s Rare Earth Elements: What Businesses Need to Know.” 2025.

AP News. “Fact Focus: Trump says tariffs have created an economic miracle. The facts tell a different story.” 2026.

Comment