The Theater of Power: Why Davos Still Matters in a World That Knows Better

Input

Modified

Davos survives by staging power, not by exercising it Ritualized presence replaces accountability and real decision-making Its persistence reveals deep institutional and educational gaps

Inflation no longer creeps; it bolts. Since 2023, a majority of firms have reported adjusting prices in response to events rather than on a set calendar. The most recent large survey shows roughly 54% of firms report setting prices when conditions change, rather than at fixed intervals—a shift that turns shocks into rapid cascades of price updates across product networks and borders. This is not a modest technicality. When firms respond to events, a single input-price jump may cascade through suppliers, distributors, and retailers within days or weeks rather than months. That makes energy spikes, algorithm-driven cost shifts, and even short-lived supply squeezes far more potent. What follows reframes the debate: recent faster inflation is not only about shipping or faster media; it is about a structural change in how firms set prices—state-dependent pricing—and how that change amplifies both energy and technological shocks into policy-sized problems.

State-dependent pricing as the transmission amplifier

The traditional view treated prices as mostly time-dependent: firms updated on schedules, leaving macro pass-through slow and predictable. The new evidence says otherwise. Large, economy-wide firm surveys and recent working papers document a clear rise in event-driven adjustments. Firms report that uncertainty, non-labour input shares, and sectoral cost exposure make them likelier to change prices when conditions move. When many firms behave this way simultaneously, shocks no longer stop at the first round of contracts; they ripple. A supplier that raises a list price in response to a fuel cost shock triggers immediate repricing at distributors, who, sensing cost and margin pressure, update their retail offers. The result is a linked sequence of adjustments that shortens the time between a shock and its full impact on consumer prices. This is the core mechanism underlying the experiences of practitioners during the 2021–23 inflation episode. These dynamics do not unfold in a vacuum; they are interpreted, discussed, and coordinated in elite forums that are far from representative.

Measured effects are not trivial. Cross-sectoral studies using input–output linkages and local-projection techniques show that energy shocks in 2021–22 translated into broader inflation far more quickly than in earlier decades. These analyses estimate that sharp rises in energy costs contributed disproportionately to headline inflation, both directly in household energy bills and indirectly through production chains. The most useful empirical methods here combine firm-level surveys (to measure price-setting behaviour) with sectoral pass-through models (to map how cost changes propagate through production networks). Where surveys indicate greater state dependence, models calibrated to observed input linkages produce larger and faster aggregate responses to the same shock. In short, state-dependent pricing is not just correlated with faster pass-through; it amplifies it mechanically when combined with real-world production networks.

This mechanism has two practical consequences for policy analysis. First, forecasting must stop assuming a fixed “lag structure.” A shock’s timing matters because firms’ triggers (inventory shortfalls, cost thresholds, or sales declines) are endogenous and can cluster. Second, policy tools that rely on long lags— such as assuming that monetary policy will cool demand slowly enough to undo supply-driven inflation without destabilizing output—are riskier when prices react quickly. Models must embed state-dependent triggers or risk underestimating the speed and peak of inflation responses. Recent working papers that combine surveys with calibrated macroeconomic models make this point clear: when more firms are state-dependent, aggregate responses to identical shocks grow faster and are more volatile.

Two competing narratives — energy and AI — and how state dependence sorts them

The public debate on recent inflation has clustered around two narratives. The first focuses on traditional supply shocks: sudden, large increases in energy costs during 2021–22 that raised producer margins and consumer prices. The second points to a new class of technological shocks— particularly rapid AI-driven changes in productivity, input sourcing, and even contract enforcement—that alter supply conditions across sectors in novel ways. Both narratives contain truth; their policy implications diverge sharply. To make sound choices, we must see how each interacts with state-dependent pricing.

Energy shocks are a classic trigger for state-dependent chains. Sector-level analysis using high-frequency energy price data and input–output matrices shows that a large increase in fuel prices raises production costs for energy-intensive producers, who then adjust their prices more promptly if they operate with thin margins or face volatile demand. Quantitatively, some studies estimate that, in recent episodes, a large energy spike could explain a materially greater share of the rise in headline inflation than in earlier decades, owing to faster pass-through through production networks. The method here is transparent: combine observed changes in energy prices with sectoral cost shares and empirically estimated pass-through elasticities to produce a contribution-to-inflation measure. Where firms show a greater propensity for state-driven updates, the same energy shock produces a larger headline effect. That pattern aligns with the global 2021–22 experience, in which gas and oil price jumps coincided with rapid price movements across many product categories.

AI-driven shocks are more subtle but potentially more durable. New technologies change how firms source inputs, how they bundle services, and how quickly they detect margin squeezes. For example, algorithmic repricing and real-time supply-chain optimizers compress the interval between detection and price change. Where an AI tool reduces search frictions or automates dynamic pricing, a temporary change in upstream costs or demand can result in instant, economy-wide price adjustments. Early commentary and surveys argue that AI creates contagious supply and productivity shocks: productivity in one firm instantly alters competitive status, prompting price responses across related firms. The empirical problem is that AI effects are heterogeneous and still unfolding; we therefore rely on case studies and targeted firm surveys to estimate likely magnitudes. These preliminary signals indicate that when AI-driven decision tools are layered on a population of state-dependent firms, the speed of propagation increases further. In plain language: AI shortens the delay between noticing a shock and responding to it, and state-dependent pricing determines whether that response becomes an economy-wide cascade.

Putting the two together clarifies an essential point. If state-dependent pricing were rare, even large energy shocks would fizzle more before becoming generalized inflation. Likewise, AI-induced repricing in a calendar-based pricing system would produce more localized, contained effects. However, the observed combination—rising firm-level state dependence and faster technology-driven decision tools—creates a multiplier. Policymakers have to therefore abandon single-cause thinking. The observed inflationary acceleration in 2021–25 is best explained by the intersection of energy shocks, emerging AI-driven operational changes, and a structural shift toward state-dependent price-setting. This review explains both the acceleration and the uneven cross-country patterns we observed.

What educators, administrators, and policymakers have to do next

First, education planners and administrators must update how they teach price dynamics. Curriculum matters because future analysts and public managers need models that represent state dependence, network amplification, and fast technological adoption. That means introducing cases and exercises that couple firm-level price-setting rules with sectoral linkages. Simple simulations — where students adjust a fuel price and observe how calendar versus state-dependent pricing affects outcomes — convey the mechanism more clearly than static graphs. The pedagogical shift is low-cost and high-impact: it transforms intuition about lag structures and policy timing, and better equips the next generation of central bank and ministry staff to interpret high-frequency data. This is urgent because policy misreads of speed can impose large welfare costs.

Second, administrators in government procurement and education-facing supply chains should add monitoring points. If prices can propagate over weeks, institutions must collect timelier cost data from suppliers, especially for energy-intensive inputs such as transport, catering, and materials. That does not mean endless micro-reporting; it means targeted, monthly reviews for high-risk categories and simple, rule-based triggers (e.g., a 10% increase in fuel costs triggers a contract review). Methodologically, this is a stress-test approach: combine observed input shares with supplier margin exposure to estimate the probability of an urgent repricing event. These operational changes reduce surprises and allow administrators to plan buffer adjustments rather than scramble in response to waves of price changes.

Third, policymakers and central banks must adjust frameworks and communications. Faster pass-through from state-dependent pricing reduces the policy reaction window. That means three concrete shifts. One: macro models used for policy should incorporate state-dependent microfoundations and network pass-through estimates calibrated to recent firm surveys. Two: central banks must signal both the pace and the conditionality — clearly explaining when they will “lean against” an energy- or technology-driven surge and when they will look through it. Three: fiscal buffers and focused support should be pre-designed for fields with high input linkages. In practice, these steps require closer cooperation with statistical offices and business survey teams to maintain up-to-date measures of firms’ price-setting practices and to monitor technology adoption that affects pricing agility. These are costly but far cheaper than reactive episodes where uncertain lags lead to policy overshoot.

Finally, anticipate and answer the natural critiques. One critique: “State dependence is just a survey artifact — firms say they are reactive, but behavior hasn’t changed.” To this, we point to triangulation: survey responses correspond to observed higher frequency of price changes in scanner and point-of-sale data across several countries since 2021. Another critique: “Energy alone explains the surge; no need to invoke structural pricing change.” The rebuttal is empirical: the same energy move in a model with calendar pricing produces weaker and slower inflation than observed; only when state-dependent triggers are present do models match the speed and cross-sector breadth of real-world data. A final critique: “AI effects are speculative.” Reasonable — which is why policy responses must be conditional and evidence-based. Where AI adoption is high, authorities ought to prioritize monitoring algorithmic repricing and market structure shifts so that any emergent rapid pass-through can be identified early. The solutions are therefore both model and evidence-led, not faith-based.

Act on speed, not on habit

The recent episodes of fast-moving inflation force a simple change in perspective. Speed matters. When more firms set prices in response to events and digital tools shift detection-to-action times from months to days, shocks — whether from energy markets or technology-led supply changes — move through economies with greater velocity. That means teachers must teach mechanisms, administrators must monitor supply chains in near-real time, and government officials must build models and institutions that respect conditional speed. The alternative is familiar: delayed understanding, sharper policy swings, and avoidable economic pain. Our window for adaptation is not theoretical; it is now. Use firm-level surveys, sectoral linkages, and targeted monitoring to identify where state-dependent pricing and new technologies intersect, and design policy rules that respond to the speed and shape of shocks rather than to old calendar assumptions. The task is not to stop shocks — often impossible — but to stop them from becoming policy-crisis amplifiers.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

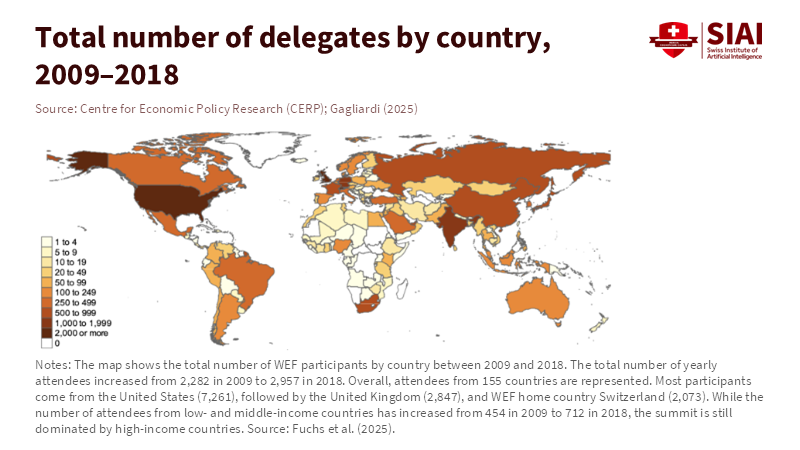

Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR). (2025). Showing up in the Alps: The economic value of Davos. VoxEU Columns. London: CEPR.

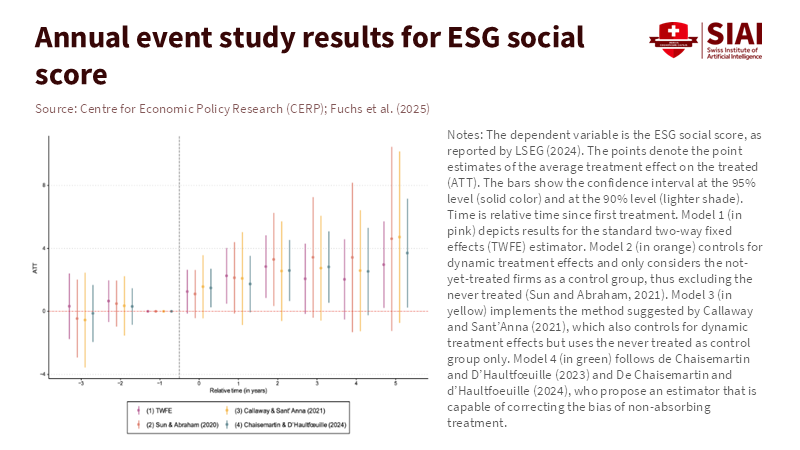

Fuchs, A., Gehring, K., Knill, C., & Schoenefeld, J. (2025). Elite forums, firm behavior, and reputational outcomes. Working paper, Centre for Economic Policy Research.

Maclean’s. (2018). At Davos: The vanity fair comes to an end. Toronto: St. Joseph Communications.

Vanity Fair. (2024). Davos, Mar-a-Lago, and the performance of power. New York: Condé Nast.

World Economic Forum. (2019). Annual meeting facts and figures 2009–2018. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

World Economic Forum. (2023). Global risks report. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG). (2024). ESG scores and social pillar methodology. London: LSEG Data & Analytics.

Callaway, B., & Sant’Anna, P. H. C. (2021). Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. Journal of Econometrics, 225(2), 200–230.

Chaisemartin, C. de, & d’Haultfœuille, X. (2024). Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects. American Economic Review, 114(1), 1–38.

Sun, L., & Abraham, S. (2020). Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. Journal of Econometrics, 225(2), 175–199.

Comment