Under Glass: How Legal Battles and Platform Politics Rewired the mobile design regime

Input

Modified

Mobile design is now governed, not just created This regime shapes how learning technologies function in schools Policy can still redirect design toward education

Back in 2012, Apple won a case where a jury awarded it over a billion dollars. They said a competitor copied key parts of their phone's design. This wasn't just about the money; it changed the game about who could claim ownership of how phones looked and worked. The idea that judges could control how a phone looks and feels made waves in the phone, app store, and design industries. This is key to understanding how mobile design has become what it is today. Now, the rules about what users see and what educators have to deal with are set by laws, platform rules, and design guidelines, not just what's popular or technically possible. It's important to get this because schools, tech companies, and government officials aren't just picking between good and bad apps anymore. They're choosing which company's design ideas will affect students' attention, access, money flow, and learning.

The legal hinge that reshaped the mobile design system

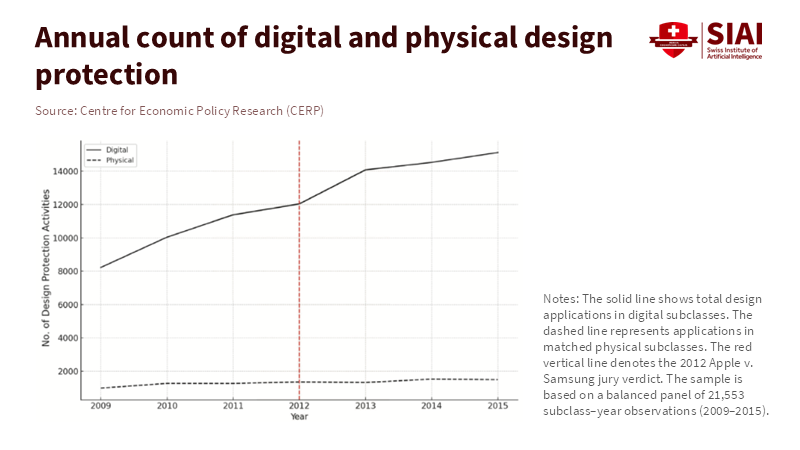

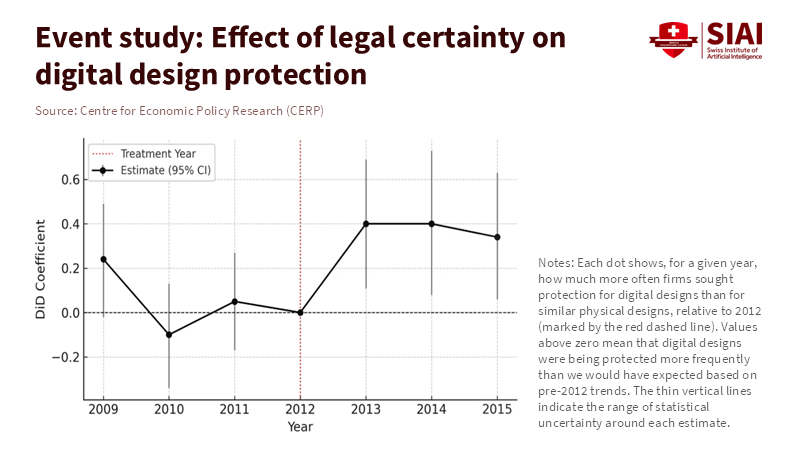

The 2012 legal case was a turning point for mobile design. It pushed things toward norms controlled by the platforms. This isn't just a crazy idea; it's how things are set up. The trial that led to the 2012 decision created a new system for who controls interface design. Big phone companies learned that how things looked and how people interacted with them weren't just about engineering. They were valuable things that could be defended, licensed, or fought over in court. Soon after, the two main systems, Apple and Google, began drafting their rules for how things should look and work. Apple's approach was based on system-wide guidance for human interfaces, while Google promoted a single visual style, which became Material Design, across all devices. These actions turned design into a means of governance. Platform owners could use software development kits (SDKs), developer guidelines, and reviews to enforce a consistent look and feel and a set of interaction methods. As a result, legal decisions, platform rules, and internal design systems interact to shape how experiences are created and how revenue is generated from them.

This control is real, not just symbolic. When design rules are part of the operating system and the store review process, small developers and educational companies are required to follow them. This brings up important questions for education. When a school system chooses a group of devices or an app system, it's not just picking the hardware. It's accepting a whole package of interaction norms, business models, and platform support. These packages affect what's easy to create and what's technically expensive or not encouraged. The legal fight in 2012 helped accelerate the shift from open, scattered user interface (UI) methods to a system in which platforms control design choices on a large scale.

Platform economics and design discipline

Two related facts about the economy show why the design system matters beyond looks. First, Android and iOS split the device market, but not the money. Android has the largest number of devices worldwide, whereas Apple's platform generates more revenue per user from in-app purchases. Second, the app economy is big and growing. In-app purchases alone accounted for approximately $150 billion in 2024. These numbers aren't neutral. A design system that prefers explicit rules and a managed store helps companies and app developers to design once for a large, high-spending system. It also favors platform-native designs, making things easier and keeping people using the apps. For educators and edtech entrepreneurs, this means that where students are digitally, whether on Android or iOS, affects costs, available features, and even the types of assessments possible.

Note that market share figures for mobile operating systems are based on global tracking sources (StatCounter series through early 2026) and indicate that Android accounts for about 70% of active devices worldwide, while iOS accounts for about 29%. App economy totals are based on Sensor Tower’s market data for 2023–2024 and its 2025 report on in-app purchases. These models use panel data and store information to make widely used estimates. If national differences and smaller device sales matter for buying decisions, local data should be used. My explanation below draws on these international standards to derive conclusions applicable to most education systems.

These economic reasons help explain why many people feel that iOS apps are more polished and consistent. At the same time, Android users say their platform often has features sooner or offers more variety. This difference is real and built into the systems. Apple's stricter management of hardware and a managed developer review process leads to a smaller set of interface styles. Google's Material Design aimed to bring consistency throughout various hardware by giving developers a shared language. Both involve giving up something: either the freedom to innovate or the consistent ease of use. For schools, this means that a tightly controlled design system reduces differences and support needs but can also trap them into using one company's interaction styles and business terms.

Design systems, cognitive load, and classrooms

When students are involved, design choices matter. Mental workload theory has long shown that extra complexity in teaching harms learning. Complex interfaces create an extra load. Research from instructional design and user experience (UX) studies indicates that higher cognitive demand in interfaces is associated with poorer performance and less learning. When apps follow clear, easy-to-use patterns, like clear signs, predictable navigation, and minimal distractions, students are able to focus on the content instead of figuring out how the app works. On the other hand, when a school district allows a mix of apps built on different platform styles, teachers spend more time troubleshooting and less time teaching. The mobile design system affects cognitive ease at scale.

The classroom effect is stronger because device groups are often different. Decisions about whether to prefer one operating system for tablets or to allow students to bring their own devices affect teacher workload, access to assistive technologies, and training costs. Monitoring shows substantial differences in how students use devices at school and how these relate to their attention and achievement. Rooms in which phones and tablets are poorly managed tend to show lower performance in key subjects. Concerns about the design system are real. They appear in attention, fairness, and the cost of implementing digital learning. Administrators who don't adhere to platform-level design rules may impose additional work on teachers, reducing their time for teaching.

Policy levers inside the mobile design system

If the system is already built into operating systems and store economics, policy options aren't about changing platform power overnight. They're about directing the incentives and buying power available to public systems. First, buying rules should include ease-of-use and availability criteria, informed by cognitive demand research and platform-specific design styles. Contracts that reward apps for predictable navigation, clear error messages, and simple information will shift developers' focus. Second, reliable lists of compatible tools, managed by education authorities, should list approved UI styles and basic modules that vendors must use to be eligible for funding or placement in school stores. Third, training should focus on helping teachers connect teaching activities with the interaction styles common on the chosen platform. Otherwise, even great curriculum software will not work as well. These are small, doable changes that shift the mobile design system toward learning results rather than advertising reach.

These actions lock in platform dependence or stop innovation. But policy can be designed to avoid these problems. Buying rules can require modular application programming interfaces (APIs) and exportable data formats, enabling schools to switch vendors without losing student work. Grant programs can support design toolkits that work across platforms, translating instructional techniques into both iOS and Android styles. Finally, regulatory review, which is already happening with questions about app store fees and competition, can be aligned with educational goals to push platforms toward more transparent review practices. The key idea is that the education sector doesn't have to accept the mobile design system as inevitable. It can shape the system through specifications, management, and focused support.

In conclusion, the legal turning point in 2012 helps explain why the look and feel of mobile learning is now managed as a public asset by private platforms. This control over design has real effects on classrooms. It guides attention, shapes accessibility, and changes costs for districts, vendors, and families. We must treat the mobile design system as a policy area, not just a matter of taste. Practical steps, like buying tied to ease-of-use criteria, managed lists, teacher training focused on platform styles, and open data needs, can protect learning while keeping innovation alive. Education systems must take action. They must specify what constitutes good interaction design, support the conversion of teaching methods into platform-aligned modules, and ensure transparency in store management. If we don't, design choices made in company meetings and courtrooms will continue to shape who learns what, how well, and for whom.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Apple Inc. (2013) iOS 7 with completely redesigned user interface. Apple Newsroom.

Centre for Economic Policy Research (n.d.) The future under glass. VoxEU Columns.

Google (2014) Material Design. Google Design.

MacRumors Forums (2024) I never thought I’d see the day Android looks better than iOS. MacRumors.

OECD (2024) Students, digital devices and success. OECD Publishing.

Sensor Tower (2025) State of Mobile 2025. Sensor Tower Research.

StatCounter Global Stats (2024–2025) Mobile operating system market share worldwide. StatCounter.

Sweller, J. (1988) ‘Cognitive load during problem solving: Effects on learning’, Cognitive Science, 12(2), pp. 257–285.

The Guardian (2012) Apple v Samsung verdict and its implications for design patents. The Guardian.

Comment