India Growth Momentum and the Global Power Shift

Input

Modified

India growth momentum is strong, but its durability depends on education reform Investment gains will fade unless skills systems scale with industry demand The real test is whether growth becomes long-term capability

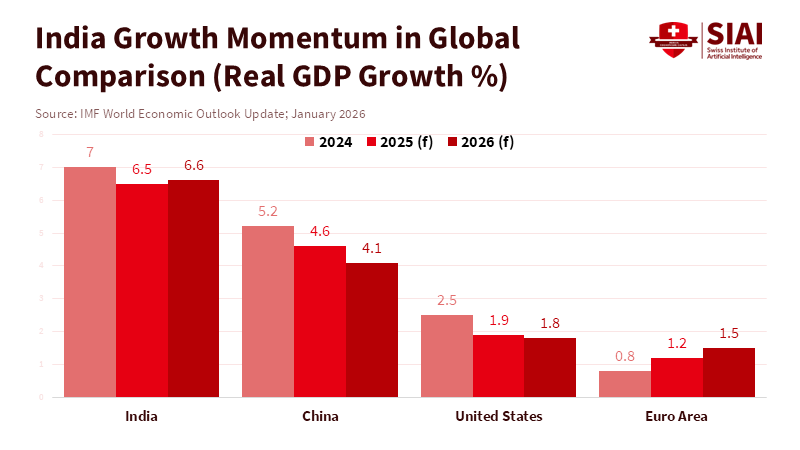

India is in a sweet spot. By 2026, it's projected to account for about 16% of the world's real GDP increase. That's a big enough chunk to change how we see global economic growth, but also small enough that choices made by Indian leaders still matter a lot. This isn't just luck. A combination of things – people wanting to buy stuff, companies investing more, and government policies focused on boosting specific industries – has given India real, lasting economic energy, not just temporary upticks. China's economy, on the other hand, is slowing down and dealing with debt, which makes it easier for India to become a key player. However, India still has its own weak spots and challenges. For those in education and government, here's the key point: This economic boom is real, but it will only benefit everyone if education, job training, and the financial system improve quickly. India has some advantages right now in terms of trade, government spending, and its young population. If it wastes these opportunities, the impressive economic numbers won't translate into real improvements in jobs, productivity, or people's ability to move up the social ladder.

What the numbers tell us about India's growth

India’s strong economic performance isn’t a one-time thing. Forecasters from both the Indian government and international organizations agree that India will be among the fastest-growing major economies in the next few years. They predict annual GDP growth of around 6.5% to 7%, depending on how you calculate it. This growth is driven by several factors: consumer spending, government investment in infrastructure, and increased investment by companies. A report from the IMF notes that India’s solid economic performance offers a key opportunity for structural reforms designed to support its aspirations to become an advanced economy by 2047. Government spending on infrastructure and programs to encourage manufacturing is boosting manufacturing and logistics. Also, people are buying more things now that the pandemic is behind us.

There are two important facts behind these numbers that educators should pay attention to. First, India has a young population – the average age is around 30. This means there's a big opportunity to improve education and skills on a large scale. Second, surveys of companies and regions show that employers are having trouble finding people with mid-level technical and management skills, even though there are plenty of entry-level workers. The message is clear: the economy is creating jobs, but not always the kinds of jobs that are needed. If schools, training programs, and certification systems don't adapt quickly, companies will either hire workers from other countries or automate jobs that trained Indian workers can fill. For example, reports from the World Bank and the Indian government show that investments and manufacturing growth will only lead to higher productivity if more students complete vocational and college programs and find jobs in their fields. Policy documents suggest that placement rates need to increase by 20–30% over the next five years.

India's growth: opportunities and limits

India has a big advantage because of its large internal market. This protects it from global economic disturbances and enables manufacturers to focus on selling to Indian customers rather than relying on exports. Government programs to encourage manufacturing, investments in transportation, and increased use of digital technology have already led to more factory investment and exports in a number of industries. These policies make it possible for India to catch up with other Asian countries in terms of productivity much faster than previously expected.

However, there are also real limitations. Greater investment from both the public and private sectors needs to be matched by improved education, faster job training, and easier access to financing for small businesses. If not, the new factories and infrastructure will either remain unused or create predominantly low-wage, low-skilled jobs.

The education system is important. Because India is so big, even small improvements in graduation rates, teacher quality, and job-relevant curriculum could produce millions more skilled workers each year. But there are still problems: coordination between national programs and local schools is uneven, certification systems for short training courses aren't recognized nationwide, and funding for lifelong learning remains low. The government needs to do three things at the same time: expand access to high-quality, accredited technical education, integrate on-the-job learning and short-term credentials into degree programs, and create a national program to help companies pay for apprenticeships. These aren't magic solutions, but they're critical points at which changes to curriculum and government spending can turn economic growth into real improvements in the job market.

What should educators and administrators do?

We need to act quickly but also be realistic about what's possible. First, government agencies should make it easier to transfer short-term job-training credentials nationwide and ensure they're recognized by employers within 1.5 years. This requires a national credential database, closer cooperation with employer groups, and a faster approval process for training programs related to manufacturing and infrastructure projects. Second, funding for job training programs must focus on results: instead of just funding programs, pay them based on how many people find and keep jobs for at least six months to a year. Third, colleges and universities should be rewarded for updating their curricula to align with the skills employers need, not just for increasing enrollment. These changes will shift the focus from simply handing out certificates to actually building skills.

Administrators should also be aware that growth won't be uniform across all areas. Coastal areas and industrial centers will likely see the most manufacturing growth, while other regions will benefit more from services and construction. This means that national programs need to be adapted to local conditions, taking into account the local industries, language needs, and transportation challenges. Finally, access to money is important: small and medium-sized businesses will be the main employers of new graduates. The government should increase credit lines specifically for companies that hire apprentices and provide loan guarantees for training investments. This reduces the risk for employers and creates a clear path from training to employment. A report by Swati Dhingra and Stephen Machin finds that workers with a job guarantee were better protected against job losses and earnings declines during economic downturns.

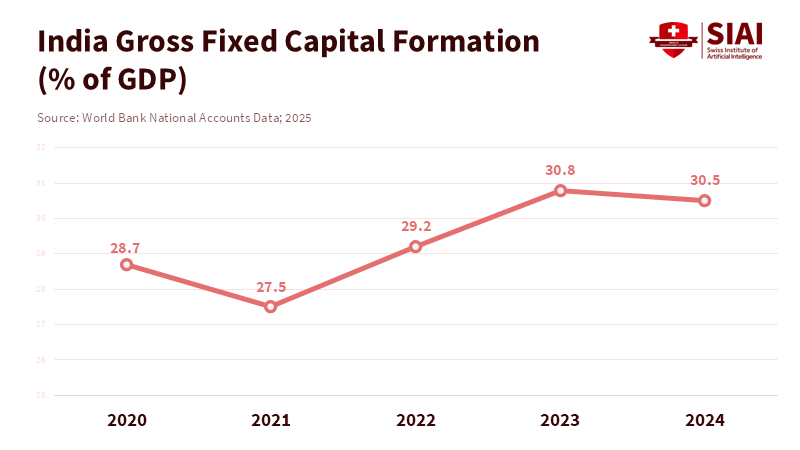

Responding to common concerns

Some people will say that India's growth is fragile because a weak Chinese economy could reduce global demand or interrupt supply chains. This is a valid concern: China's economic problems could lower demand for goods and services. However, there's also an upside. According to the World Bank, as companies look to diversify their supply chains away from a slowing China, India stands to benefit if it improves its logistics sector, reduces the cost of doing business, and keeps stable policies, since well-organized logistics are key to making India a more attractive manufacturing destination. The argument that India's growth is primarily driven by consumer spending rather than long-term investment overlooks the recent, measurable increase in investment and the government policies intended to encourage it. Investment now accounts for close to 30% of India's GDP, and investment growth has been positive in recent quarters. These figures indicate that investment is catching up with consumer spending.

Another concern is that there's a mismatch between the skills people have and the skills employers need, and that automation will eliminate jobs. This is a real risk, but the right policies can reduce it. Short-term training programs focused on skills that are difficult to automate (such as problem-solving, supervision, and maintenance) can help employees retain their jobs as companies become more digital. Also, if companies invest in training alongside automation, technology can increase productivity and wages for trained workers rather than replace them.

India's economic growth is not simply a set of numbers; it's also a choice. The strong economic forecasts, rising investment, growing foreign investment, and favorable demographics create an opportunity to translate economic strength into broad social improvements. But the numbers alone aren't enough. The key will be the quality of education, the speed and design of job-training programs, and the government's willingness to tie funding to measurable employment outcomes. For educators and administrators, this means changing incentives and making sure that training programs lead to real jobs. For decision-makers, it means treating education as infrastructure: a public good that increases the payoff of every dollar invested. If we get this right, India's rise will be more than just a statistic; it will be a lasting transformation for millions of workers and for the global economy. If we don't, the economic picture will look good on the surface but won't have lasting benefits. The choice is ours.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bloomberg News (2025) The true cost of China’s falling prices. Bloomberg.

International Monetary Fund (2026) World Economic Outlook Update, January 2026. Washington, DC: IMF.

Ministry of Commerce and Industry, Government of India (2025) FDI inflow trends and sectoral performance 2024–25. New Delhi: Government of India.

Ministry of Finance, Government of India (2026) Economic Survey 2025–26. New Delhi: Government of India.

PopulationPyramid.net (2025) India population data and demographic structure. Available demographic database.

Visual Capitalist (2026) Who is powering global economic growth in 2026? Visual Capitalist.

World Bank (2025a) India Country Economic Memorandum. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Bank (2025b) China Economic Update, June 2025. Washington, DC: World Bank.

East Asia Forum (2026) India’s economy carries its momentum into 2026. East Asia Forum.