Copyright’s Quiet Pivot: Why AI data governance — not fair use — will decide the next phase of legal rules

Published

Modified

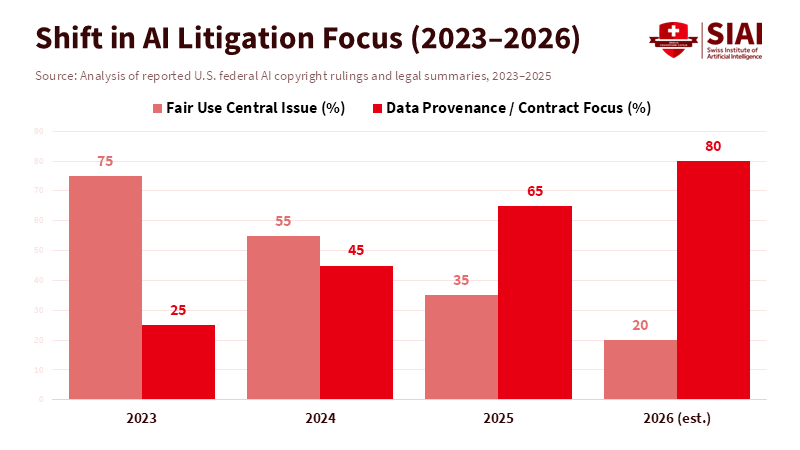

AI copyright disputes are shifting toward strict AI data governance and data provenance scrutiny Settlements and licensing deals now shape the legal landscape more than courtroom doctrine The future of AI regulation will depend on verifiable governance, not abstract fair-use theory

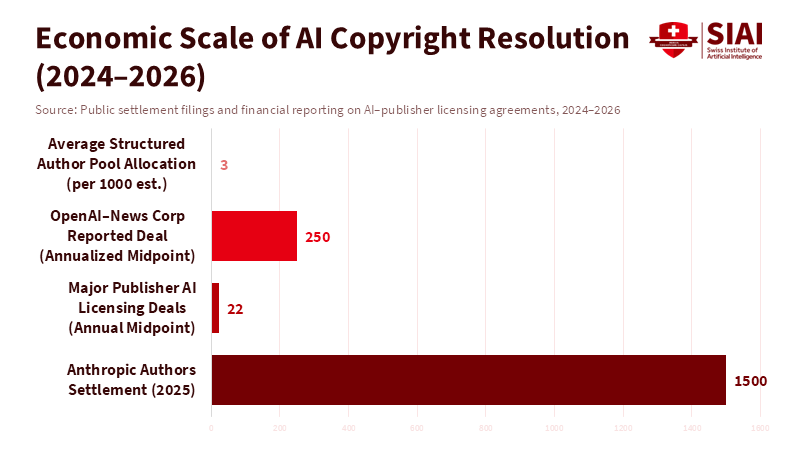

When authors and publishers went to court with AI developers, everyone thought we'd get clear answers about if it's okay to train AI using copyrighted stuff. But that's not how it's turning out. By late 2025, a big case didn't end with some fancy legal rule, but with a deal: a judge gave the thumbs up to a roughly $1.5 billion agreement between authors and an AI company. The issue was that the AI allegedly used about 465,000 books to train its models. That huge number tells us something important: not knowing the rules is costing people a lot. So, companies, publishers, and even the courts are starting to focus on something simple: can you prove where the data came from, how you got it, and that it's legit? They're not trying to make some grand statement about fair use. This isn't some legal trick. It's a big change in how we handle AI data, which is becoming the key to being responsible.

AI Data Management and the Changing Legal World

Previously, people thought copyright and AI were a simple yes-or-no question: is using copyrighted material to train AI fair, or is it against the law? That question sparked significant debate among experts and a few court opinions, but it didn't really help businesses figure things out. But in 2024 and 2025, courts began examining the same facts in a new way. Judges wanted real proof about where the data came from, what agreements covered it, whether anyone was using pirated materials, and whether you could trace what the AI produced back to specific copyrighted works. These aren't just abstract legal ideas; they're practical things companies can check. And that's important because companies can take action on this. They can maintain records, conduct audits, obtain licenses, and demonstrate the source of their data. They can't go back in time and change the Constitution. Companies with strong AI data management will face less legal risk and have a better reputation than those that don't.

According to AP News, some rights holders are now seeking to monetize through licensing agreements and business deals rather than relying solely on uncertain and lengthy court cases. And the market is reacting. By mid-2025 and into 2026, major publishers and news services were entering into business agreements with AI developers. These big deals showed everyone that there's money to be made. For AI developers who have billions on the line, paying to get data legally or at least showing they have a good reason to believe their data is legit is better than risking a court decision that cuts them off from important data. The legal fight is shifting from "Is this legal?" to "Can you prove where you got this?" And that's where AI data management comes in.

AI Data Management: Agreements, Licenses, and What the Market is Saying

The numbers are pretty amazing and tell us a lot. A settlement of approximately $1.5 billion in 2025, which was agreed upon rather than won in court, isn't just about getting paid back. It's a sign of what things are worth. It tells the people in charge of risk, the people on the board, and the people buying AI what it might cost if they don't follow the rules, and how valuable it is to have a data supply chain that you can trust. At the same time, large licensing deals between publishers and AI companies began to emerge, and the reported prices indicate that the market is rising. Major publishers are reportedly receiving millions of dollars each year for allowing AI companies to use their content, and one deal was reportedly worth $20–$25 million annually. These numbers aren't always clear, and many agreements aren't public, but the trend is evident: rights holders are getting money through contracts while the legal disputes are more about the specific facts of each case.

The courts are also helping this trend. Throughout 2025, several court decisions emphasized the details of how data was changed, accessed, and where it came from, rather than making broad general rules. In other words, the courts often didn't make a big statement about fair use, but they did make it clear that they wanted to see proof of how the data was obtained and used. This creates a predictable legal situation: if judges require proof of data origin, those who can provide it have greater leverage in negotiations, and those who can't are more likely to settle. For the people making the rules and for institutions, this means that you can prevent problems and measure how well you're doing. If a company keeps track of who gave them data, what agreements covered it, what changes were made, and how they verify that copyrighted material isn't being copied, they'll be in a better position to avoid expensive settlements or being told to stop.

AI Data Management for Schools and Organizations

If courts and the market agree that it's important to know where data comes from and to have clear agreements, then schools and universities need to make AI data management a top priority. Universities and educational companies are in a unique position: they create valuable training materials (such as lesson plans, research, and lecture recordings) and rely heavily on data from others. A good management plan should have at least three things. First, know what you have and where it came from: every dataset used in a model should be logged with basic information such as its source, licensing terms, capture date, and whether permission was granted. Second, have clear agreements: licensing and data-sharing agreements should state that model training is permitted and specify who gets credit, how funds will be shared, and how the data can be used. Third, be able to audit and control changes: schools should use reliable systems that record data changes and allow external auditors to verify that copyrighted content wasn't copied without permission.

These are real steps, not just good ideas. For example, a textbook company considering partnering with an AI company can determine whether offering a licensed feed for model training will generate more revenue than it costs to manage the rights. Similarly, a university developing its own AI tools can use models trained on data it can verify as clean, reducing its insurance costs, legal fees, and reputational risk. The government can help by supporting shared resources such as licensing marketplaces, standardized methods for recording data origins, and integrated audit tools. These shared resources lower costs and reduce the temptation to take advantage of the system while still protecting creators' rights. To put it simply, good AI data management is also good for the economy.

AI Data Management: Addressing Concerns and Establishing Norms

Some worry that settlements and private licensing will only benefit big companies and create a system in which only those who can pay get access, thereby limiting the flow of information. That's a valid concern. If only big publishers can profit from their archives, smaller creators might be left out, which could harm the public interest. But the alternative – a free-for-all where everyone grabs data without permission, leading to lawsuits – has its own problems: it erodes trust, causes unpredictable takedowns, and leads to models trained on unreliable data. The solution isn't one or the other. It needs to combine market contracts with public safeguards. That means being watchful for antitrust issues to prevent licensing that excludes others, supporting exemptions for research under clear rules, and requiring transparency so that outsiders can check whether models use licensed or unlicensed content.

Some people argue that management rules will be circumvented or become so costly that they slow innovation. The answer is to adjust based on the evidence. Simple, cheap ways to show where data came from – like a register of datasets that machines can read and a tiered licensing system – can get most of the benefits of compliance without a lot of red tape. When private markets don't provide broad access for research and education, public money can create curated, licensed datasets for non-commercial use. And the courts will still be important. Narrow rulings that focus on the facts of each case and emphasize where data came from aren't a replacement for laws, but they do influence how the market behaves. The combination of court oversight, negotiated contracts, and policy support makes it harder to claim ignorance as a defense and more appealing to build compliance into product design from the outset.

The $1.5 billion settlement is a crude measure that signals a more delicate situation: legal disputes over AI are shifting from abstract arguments to real-world actions. For creators, companies, and schools, the main question has become whether models can prove, with records and contracts, where their data came from and how it was handled. That's what AI data management provides. Policymakers should stop asking only whether training is fair in theory and start setting minimum standards for data provenance, funding shared licensing resources, and protecting non-commercial research channels. Schools should manage their archives, document them, and, when appropriate, monetize them under standard terms. Industry should use data formats that work together and independent audit systems. If we do this, the market will reward clarity. If we don't, we'll end up with costly settlements, broken norms, and a legal environment that discourages innovation rather than guides it. The challenge ahead isn't just legal or technical. It's a management problem that we can solve – if we create the systems to prove it.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Associated Press (2025) ‘Judge approves $1.5 billion copyright settlement between AI company Anthropic and authors’, Associated Press, 2025.

Debevoise & Plimpton LLP (2025) AI intellectual property disputes: The year in review. New York: Debevoise & Plimpton.

Digiday (2026) ‘A 2025 timeline of AI deals between publishers and tech’, Digiday, 2026.

Engadget (2025) ‘The New York Times and Amazon’s AI licensing deal is reportedly worth up to $25 million per year’, Engadget, 2025.

European Parliament (2025) Generative AI and copyright: Training, creation, regulation. Directorate-General for Citizens’ Rights, Justice and Institutional Affairs. Brussels: European Parliament.

IPWatchdog (2025) ‘Copyright and AI collide: Three key decisions on AI training and copyrighted content’, IPWatchdog, 2025.

JDSupra (2025) ‘Fair use or infringement? Recent court rulings on AI training’, JDSupra, 2025.

Meta Platforms, Inc. & Anthropic PBC litigation reporting (2025) ‘Meta and Anthropic win legal battles over AI training; the copyright war is far from over’, Yahoo Finance, 2025.

Pinsent Masons (2025) ‘Getty Images v Stability AI: Why the remaining copyright issues matter’, Pinsent Masons Out-Law, 2025.

Reuters (2024) ‘NY court rejects authors’ bid to block OpenAI cases from NYT, others’, Reuters, 2024.

Reuters (2024) ‘OpenAI strikes content deal with News Corp’, Reuters, 2024.

Skadden, Arps, Slate, Meagher & Flom LLP (2025) Fair use and AI training: Two recent decisions highlight fact-specific analysis. New York: Skadden.

TechPolicy Press (2025) ‘How the emerging market for AI training data is eroding big tech’s fair-use defense’, TechPolicy Press, 2025.

Comment