When Cheap Imports Break: Why Trade Resilience Must Replace Naïve Efficiency

Input

Modified

Trade resilience has real economic value in a volatile world Protection can act as temporary insurance, but productivity is the stronger long-term hedge Policy must price trade risk honestly and invest in domestic capacity

Global food markets don't just bend; they break. Back in 2022, the Food and Agriculture Organization's (FAO) global food price index soared to an all-time high. As a result, millions more people faced hunger. This wasn't just a random jump; it was a clear sign of problems with concentrated supplies and fragile supply lines. That year, we learned a hard lesson: cheap imports seem great until the system that brings them to you shuts down.

The solution is simple, but it might sting a bit. We need to stop thinking of trade as something that always favors the lowest price. Instead, we should see strong trade systems as a valuable thing—like an insurance policy. It can be worth it to have some temporary protections, extend targeted support, and keep money flowing into growing our own food production.

Suppose we look at it this way, actions that might have seemed like steps backward or a waste of money can make sense if they lower the chances of really bad shortages. This changes the conversation: protecting ourselves can be a good backup plan, but getting better at producing our own food is the best way to avoid problems in the first place. So, for teachers, leaders, and those who make the rules, the message is clear: what we teach, where we put our money, and how we handle trade should all be about creating strong, reliable food systems, not merely chasing the lowest prices.

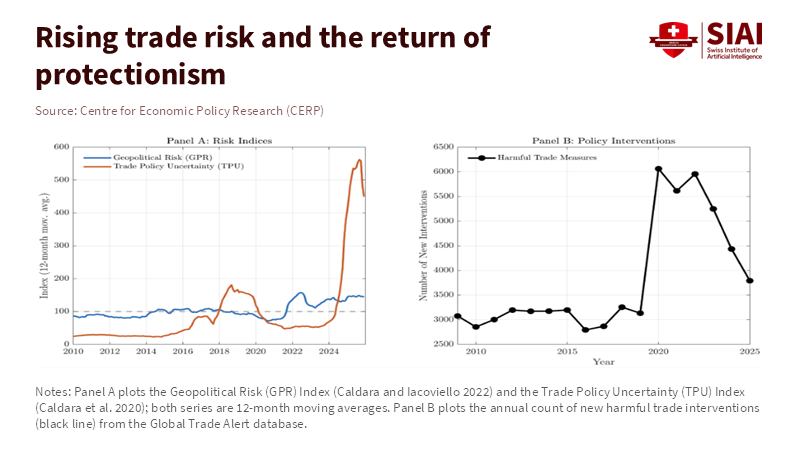

Trade Risk Has Changed the Rules of Global Food Markets

Trade works best when you can count on getting goods from other countries and selling your own products easily. If that goes wrong, many common solutions don't work anymore. Markets are good at pricing in normal risks, but they struggle when there are big, widespread disruptions. Companies can obtain insurance or identify alternative suppliers, but this can be expensive and may not fully protect them when the whole world is affected.

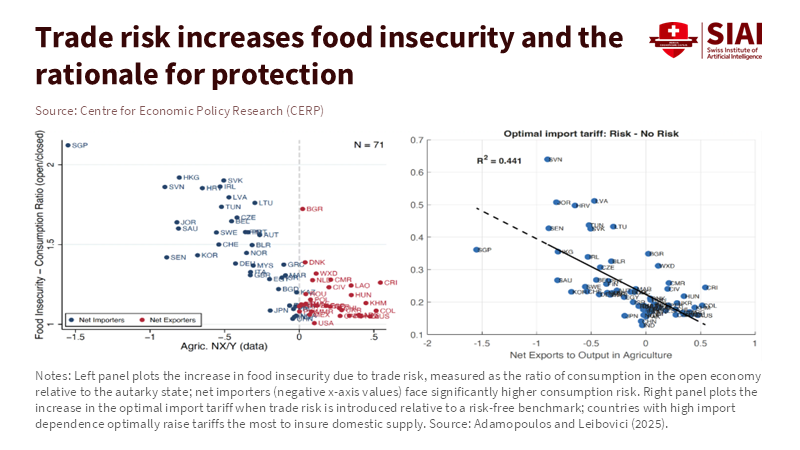

Most importantly, when things go wrong, businesses often don't fully realize how much it costs society when there isn't enough food—things like people not getting enough to eat, kids missing school, and a less educated workforce. Because these things affect everyone, the government needs to step in, even if it looks like they're just protecting local industries. The real question is whether the cost of protecting ourselves is less than the cost of dealing with a major, long-term food shortage.

The events of the last few years make this very clear. When major exporting countries halted or reduced shipments, the countries that relied on those imports experienced significant swings in food prices and, at times, serious shortages. In 2022 and 2023, several events occurred simultaneously—droughts, export restrictions, and a major disruption to Black Sea exports due to political issues. This all led to big jumps in the prices of grains and cooking oils.

These price increases hurt countries that import a lot of food the most, especially those that didn't have a lot of extra money to help lower the cost of imports or cushion the blow of problems at home. It's not just that things got more expensive; it also puts kids at risk of not getting enough schooling and healthcare, which hurts their future. According to the World Bank, projections show that up to 950 million people could be severely food insecure through 2030 if prompt action is not taken. Ignoring these mounting global risks and treating them as minor issues that can be solved with simple contracts underestimates the seriousness of the problem.

When Markets Underprice Risk: The Case for Temporary Protection

If trade is risky, then having some protections in place makes sense. Things like taxes on imports, minimum price rules, and support for local farmers can help boost our own food production. This might seem inefficient, but it functions as a safety net. It works like this: by making it more appealing to produce food at home, the government increases the amount of food available locally. This lowers the chance that a problem with foreign supplies will turn into a famine at home.

However, this safety net comes at a cost. Taxes on imports can raise consumer prices and slow economic change. Worse, if countries focus too much on protection rather than on improving their own production, they might never catch up in terms of crop yields or in modernizing their systems. This would leave them always at risk of higher costs.

Recent events show that this is happening. After the disruptions of 2020–2023, many governments used border controls and support for farmers to lessen the immediate pain. At the same time, things like non-tax rules and regulations have become more common and have a big impact on the economy, similar to high taxes on imports. The UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) estimates that some of these rules can be akin to facing a 20% or higher tax.

This explains why countries that import large amounts of food often have stronger agricultural protections than those that export food. It's not because they want to; it's because they feel they need to protect themselves more. Still, people in charge need to know the difference between sensible, temporary protection and becoming reliant on it forever. The most effective way is to use short-term border controls carefully. Pair them with emergency reserves or vouchers for those who need them, and have a clear plan for changes that boost productivity so you don't need as much protection in the future.

Productivity Is the Strongest Form of Trade Resilience

Protecting ourselves with taxes on imports is a second-best option. The best way to protect ourselves is to become more productive at home. Better crop yields, improved storage, faster roads in rural areas, and stronger supply lines mean we don't have to rely as much on food that travels long, risky routes. These improvements also increase incomes and the government's ability to respond, making it cheaper and easier to provide public support in the future. Best of all, productivity gains last and create other good things like more jobs, better nutrition, and better schooling. They turn a constant policy cost into a one-time investment that keeps paying off.

Between 2023 and 2025, we saw mixed results. Global grain stocks and production recovered in some years after the 2022 shock, but problems at ports and sudden changes in trade flows created fresh uncertainty in 2023–24. UNCTAD noted renewed pressure on freight rates and shipping reliability from disruptions around the Red Sea and other chokepoints. These upheavals make local storage and flexible supply lines even more important. Smart investments include: better crop types that reduce seasonal shortages; systems that reduce food loss after harvest; and adaptable purchasing systems that can use local surpluses when import routes close. These aren't fancy solutions. They're practical, long-term, and support the market. They also reduce the necessity of protection, because a more productive local sector can meet more demand without taxes on imports.

Designing Policy for Trade Resilience at Home and Abroad

If we agree that strong trade systems are important, then the plan should focus on three things: trade policies that evaluate risk, public money targeted at building strength, and investments in people that make productivity gains last. For teachers and leaders—who design what we learn, provide support services, and train workers—the task is clear. What we teach needs to include how to assess risks in supply chains for future managers and public workers. Agricultural colleges should focus more on storage science, supply lines, and purchasing management. Public leaders must learn to value projects that build capacity not just for increasing crop yields but for the safety net they create for everyone.

When it comes to money, governments should have clear emergency funds and adaptable safety nets. If prompt protection is used, it should be temporary and linked to investments that measurably increase capacity. This means pairing short-term taxes on imports or import limits with targeted investments in irrigation, seed systems, rural roads, and grain storage. For donors and development banks, the focus should be on funding projects that raise the long-term level of domestic supply rather than providing constant subsidies that create dependency. The idea that this approach is secretly protectionist misses the point. The goal isn't to hide forever but to have a temporary cushion while productivity takes hold. These choices are about good policy design, not just following ideology.

Some might argue that protection makes agriculture political and encourages corruption. Others might say that investing in productivity is slow and might not prevent immediate shortages. There's truth to both. Protection can be taken over by special interests. To prevent this, measures must be rule-based, open, and have a set end date. Public finance institutions should link support to clear project goals that clearly increase capacity, not just to preserving price floors. On the second point, temporary measures are just that: temporary. Emergency reserves, targeted cash payments, and conditional taxes can protect the most at risk while productivity improvements—which take longer to implement—move forward. The real mistake is to rely on either one alone. Having protection without a plan for productivity makes things inefficient. Focusing on productivity without any safety net leaves people at risk of terrible outcomes.

A further challenge is the global political economy. Rich-country subsidies and market distortions still affect global prices and can discourage developing countries from diversifying. That's why a global partnership is essential. Global emergency plans for food aid, trade rules that avoid unnecessary export limits, and greater transparency in shipping and inventory data would reduce risk for everyone. The World Trade Organization (WTO) and related institutions play a role here, as do data platforms that enable importers to see risks in real time. The point isn't to be completely self-sufficient. It's about being strategically strong: use trade when it's reliable, and plan for when it's not.

Going back to where we started: the market price of a cheap import hides the cost of insuring against problems in trade. That cost is paid in missed school, poor health, and lost futures. We can either cover it quietly with occasional protective measures or be open about it and invest in ways that reduce the need for protection. The practical plan is threefold: teach future managers in both the public and private sectors about supply-chain risk and resilience; invest public money in productivity that reduces risk; and allow measured, temporary insurance tools when markets don't fully cover systemic risk. This entails moving beyond simply praising or blaming and instead focusing on design: use protection as a short-term safety net, fund productivity as the permanent fix, and link both to clear, verifiable measures that can be checked by citizens and donors. Strong trade systems aren't just a nice idea. They're a way of choosing which risks we're willing to take and which we pass on to future generations. Make that choice clear, and policies will be honest, effective, and humane.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Consilium (2023) Ukrainian grain exports explained. Council of the European Union.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2023) Food Price Index. Rome: FAO.

Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) (2024) World Food Situation: Global cereal supply and demand brief. Rome: FAO.

UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2023) Hidden exposures: Domestic supply chains spread foreign trade risks. Geneva: UNCTAD.

UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) (2024) Review of Maritime Transport 2024. Geneva: UNCTAD.

World Bank (2023) Food Security Update, October–November 2023. Washington, DC: World Bank.

World Trade Organization (WTO) (2023) Report on G20 trade and investment measures. Geneva: WTO.

Baqaee, D., Farhi, E., Maggiori, M. and Tirole, J. (2024) Trade risk and optimal trade policy: Lessons from food security. CEPR VoxEU Column.

Carvalho, V.M., Nirei, M., Saito, Y.U., and Tahbaz-Salehi, A. (2023) Supply chain disruptions and the propagation of trade shocks. CEPR VoxEU Column.

OECD and FAO (2023) OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2023–2032. Paris: OECD Publishing.

Comment