Section 702 Reform and the AI Race: Securing Privacy Without Losing the Future

Input

Modified

Section 702 reform must protect privacy and security AI competitiveness does not require unchecked surveillance Clear legal limits can strengthen trust and innovation

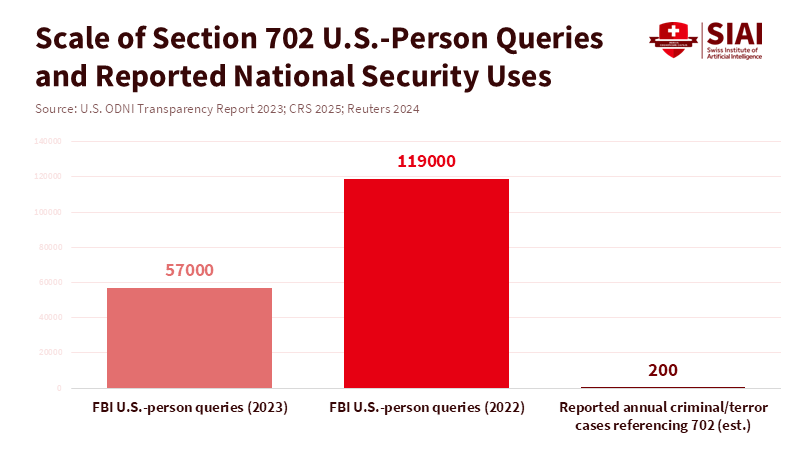

Reports from 2023 and watchdog groups indicate that U.S. government agencies conducted approximately 57,000 warrantless searches. These backdoor searches examined Americans' private messages stored in systems containing data gathered under Section 702 of the law. This number is important for two reasons. First, it shows that a law meant to target foreign people has been used on Americans. Second, the issue isn't just a small mistake, but a problem with the entire system. This number forces us to choose between two options. One, we can accept the government having broad search powers that aren't very secure legally if they make us safer. Alternatively, we can set legal limits that protect people's information while still allowing the government to do its security work. The choice is what we must decide when we weigh privacy, education, and the global race to develop AI. This decision should guide how we revise Section 702, rather than simply renewing the existing law.

Changing Section 702: National Security, Privacy, and AI Competition

In recent years, courts and oversight bodies have been examining Section 702 more closely. According to a 2025 decision by the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York, the FBI's warrantless searches of Section 702 databases were found to violate the Fourth Amendment. However, government agencies and some politicians argue that Section 702 provides them with important information and warnings that they cannot obtain in any other way. This might be true, which is why Congress is unsure about changing the law.

However, the law should be changed quickly for legal and moral reasons. People expect their privacy to be protected. The Fourth Amendment to the Constitution guarantees the right to privacy. The main problem is that, as the system works now, a lot of foreign information is collected and stored in searchable databases. People can then use tools to search these databases. This means that collecting foreign information turns into a way to search Americans' information without a warrant. So, changing Section 702 must do two things at once. It must stop people from doing routine searches of Americans' information without a warrant. It must also allow for quick, closely monitored searches in the event of an urgent threat. These two goals can be achieved. Instead of completely banning the law or renewing it without changes, we need to change specific parts of it.

The changes should be both technical and legal. For technical changes, government agencies can ensure they search only for specific items, keep a record of every search, and use computer programs to redact Americans' information unless they have a court order. According to a report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence, recent statutory reforms now require clearer rules on when warrants are required for searches involving Americans or things in America, as well as processes for quickly obtaining court approval for emergency searches. The report also notes that these changes intend to safeguard essential tools for national defense. It would also make searches subject to review and challenge in court. This is can make a big difference for schools, research centers, and education technology companies. If Section 702 is used loosely, it could put student data and research at risk. But, if the law is changed to have clear limits, it can protect privacy yet still allowing investigators to act when there is a crisis. The right changes can reduce legal risks and increase trust in the system.

Section 702 Reform and the AI Data Trade-Off

A report from the Office of the Director of National Intelligence noted a sharp decline in Section 702 searches of Americans' information, dropping from 57,094 in 2023 to 5,518 in 2024. Some people argue that having more data helps to create better AI. They worry that if privacy rules are too strict, it will slow down AI progress in America, while other countries have open access to data. This worry mixes up two different things. One is the secret information that intelligence agencies use. The other is the large, tagged datasets that companies use to create AI models.

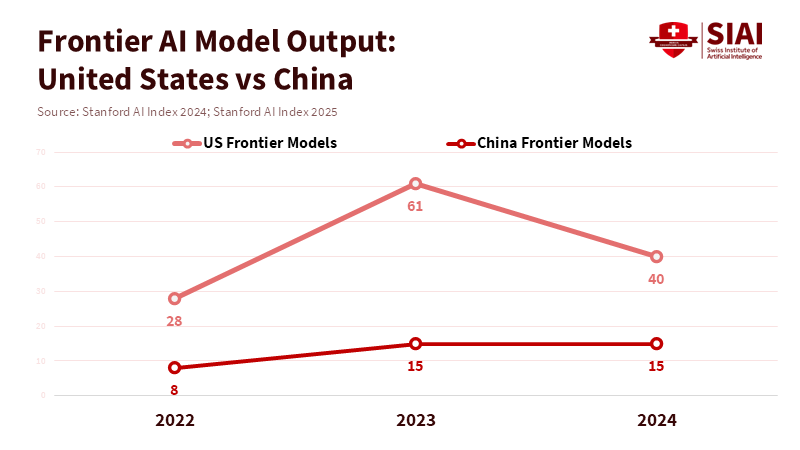

The AI Index at Stanford indicates that U.S. institutions produced many of the best AI models in 2023–24. According to the Stanford Artificial Intelligence Index Report 2025, the gap between the top-performing American and Chinese AI models narrowed significantly in 2024, with differences on key benchmarks dropping to just a few percentage points. However, this does not suggest that intelligence agency data is the main factor driving these improvements. It shows that factors such as computing power, engineering, open data, and policy choices all affect the quality of AI models. This is a competition among systems, not merely about one law.

For example, reports say that there were about 57,000 backdoor searches in 2023. Congress changed Section 702 in 2024. In 2025, courts questioned aspects of the searches' conduct. According to a report from the Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board, there are no definitive figures available on the number of cases Section 702 has helped, making it difficult to assess its exact impact. As a result, we cannot determine with certainty the extent to which Section 702 benefits commercial AI models. We can estimate that Section 702 might provide a modest boost to AI used for counterterrorism or cybersecurity. These boosts can be important in investigations where lives are at risk. However, they are less important for general-purpose language models used in educational tools. For those models, open datasets, artificial data, learning with others, and partnerships between universities and companies are much more important.

Policy should reflect these things. It would be a bad idea to ban entire types of data just because they were collected by an intelligence agency. This would harm university labs and startups that rely on lawful data to train AI models for educational applications. Instead, Congress can create legal frameworks for the use of data. These methods would enable the use of useful information for research and product development, provided it is anonymized, verified, or synthetic. This policy would enable educators and education technology companies to develop effective tools while protecting people's rights. Education leaders should request government funding to create secure public datasets and to secure student privacy when using AI models.

Changing Section 702: Policy Amendments That Protect Both Safeguarding and Innovation

A well-designed set of changes can clarify the law and protect innovation. First, require a warrant for any Section 702 search involving an American person or something in America. Allow a narrow exception for emergencies. Make sure the exception is quickly reviewed by a court. Second, ban the collection of information about people and close loopholes that allow agents to target communications solely because they mention an American person or topic. Third, set strict limits on how long data can be retained and automatically redact American information. Fourth, require that every search is recorded and that public reports are made so that Congress and the public can see what is happening over time. Finally, allow independent people to speak to the court that reviews foreign intelligence queries. This will give privacy a voice in secret proceedings.

These steps are not impossible. Modern logs and computer checks can record who did a search and why. Computer privacy tools can enable analysts to find statistical information without exposing raw messages. Emergency authorities can be made narrow and subject to court review. Changing the law doesn't mean government agencies have to stop working. It means they must operate under clear rules with technical safeguards. This change will lower legal risks. It will also strengthen the system. Government agencies that follow the law and command citizen trust will receive more support from technology companies and foreign partners.

Some people will worry that imposing limits will give our rivals an advantage. They worry that China will move faster because its data rules are less stringent and its government supports data collection. This fear is real, but it shouldn't stop us from making judicial reforms. The U.S. still leads in AI model creation, research, investment, and education. The AI Index at Stanford and other studies show that the U.S. made many more important AI models in 2023–24. The difference has become smaller, but the solution is not to remove legal limits on searches at home. The solution is to fund public data resources that protect privacy, support open research, and increase investment in engineering and computing power. These policy changes combine respect for civil rights with long-term competitiveness. For educators and administrators, the lesson is clear. Support legal transparency that protects students. Also, support public datasets and funding that allow students and researchers to stay the best in the world.

The large number of searches done without warrants is a warning. It shows that small, unclear fixes won't address the system's main problem. The way forward is to combine legal changes with technical reforms. Write a warrant rule for searches of American information. Close loopholes in information collection about people. Create logs and automatically hide American information. Fund public data resources for research and education that protect privacy. These moves will protect both national security and personal freedom. They will also protect the schools, labs, and startups that create the next generation of AI talent and tools. Careful changes to Section 702 are possible. And it should be.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Brennan Center for Justice (2023) Section 702 of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act: A resource page. New York: Brennan Center for Justice.

Cato Institute (2025) ‘Federal court rules FISA Section 702 “back door” searches unconstitutional’, Cato at Liberty Blog, 22 January.

Congressional Research Service (2025) FISA Section 702 and the 2024 Reforming Intelligence and Securing America Act. CRS Report R48592. Washington, DC: Congressional Research Service.

Electronic Frontier Foundation (2025) ‘Federal court rules backdoor searches of Section 702 data unconstitutional’, Deeplinks Blog, 22 January.

Lawfare (2026) ‘It’s time to renew Section 702 of FISA permanently’, Lawfare Blog, 4 February.

Reuters (2024) ‘US to ask court to renew domestic surveillance program before April expiration’, Reuters, 29 February.

Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (2024) AI Index Report 2024. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

Stanford Institute for Human-Centered Artificial Intelligence (2025) AI Index Report 2025. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

The Associated Press (2024) ‘Biden signs bill extending a key US surveillance program after divisions nearly forced it to lapse’, Associated Press, 20 April.

The Brookings Institution (2026) ‘A key intelligence law expires in April and the path for reauthorization is unclear’, Brookings, February.

The Verge (2025) ‘FBI’s warrantless “backdoor” searches ruled unconstitutional’, The Verge, 27 January.

CNN (2026) ‘FISA Section 702 renewal faces frustration in classified hearings’, CNN Politics, 9 February.

NextGov (2026) ‘White House to hold meeting on renewal of controversial surveillance authority’, NextGov, February.

Comment