The Cost of Policy Uncertainty: Why Waiting Breaks Growth

Input

Modified

Delayed investment is the hidden tax of policy uncertainty across all economies Unclear rules turn rational caution into long-term growth loss Predictable policy is not cosmetic reform; it is a core economic growth tool

When policies become risky, companies and people do what you'd expect: they hold off. In the first three months of 2025, the U.S. Economic Policy Uncertainty index jumped dramatically, about 68% higher than recent peaks. Models suggest that such a jump can cut GDP growth by more than 1% over the next couple of years. This isn't just theory; it's a real cost that affects decisions, causing delayed investments, higher borrowing costs, hiring freezes, and less innovation. These delays add up, turning temporary hesitation into lasting damage to how much we can produce. The bottom line is clear: when policies are hard to predict, growth slows, not just in struggling countries but in developed ones as well.

Policy uncertainty and investment: the global pattern

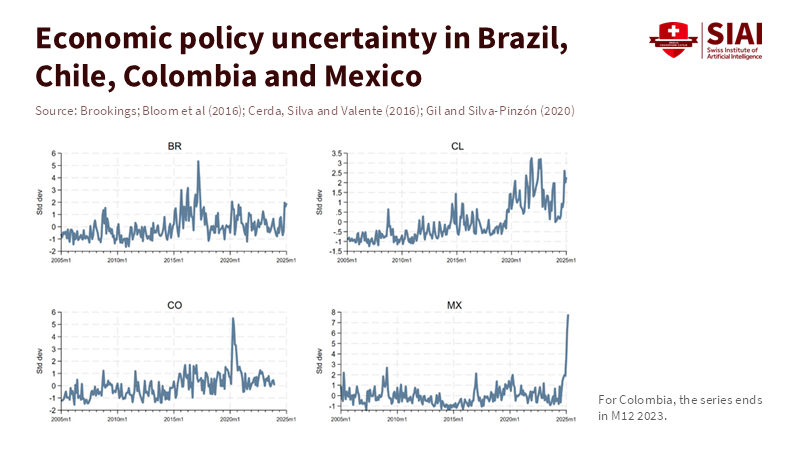

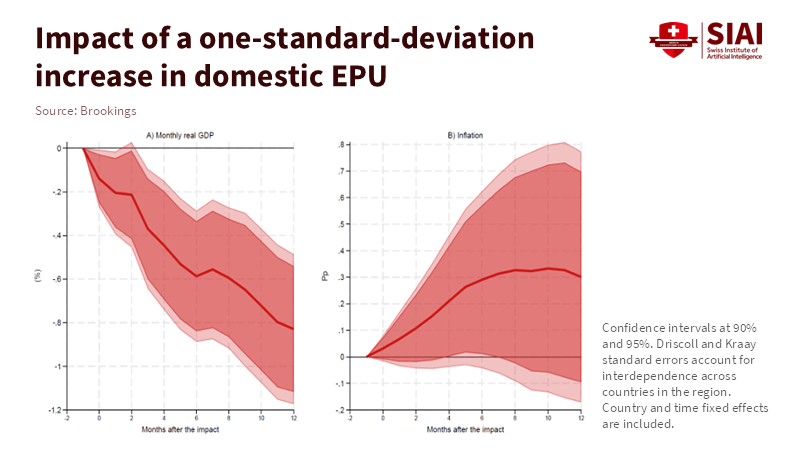

The proof from Latin America is much clearer than it was five years ago. Recent studies show that local economic policy uncertainty creates financial problems right away and, in the medium term, causes output to shrink. Stock markets become unstable, borrowing costs rise, and exchange rates fall soon after a policy surprise. Then, as companies rethink their future earnings, they cut back or cancel investment plans. These problems happen everywhere trade and money connect countries. Latin America is just one example. An analysis of four major Latin American economies shows that local uncertainty shocks behave like supply-side shocks: output falls, and inflation rises, affecting both the financial and real economies. It is the immediate financial reaction, combined with the later drop in real demand, that turns a short-term policy event into a lasting downturn.

Pakistan shows the same thing on a company level. Studies of companies show that high economic policy uncertainty reduces investment efficiency and lowers borrowing and spending. When companies face unclear tax rules, unstable regulations, or sudden policy changes, they not only have higher borrowing costs but also don't know what their future earnings will be. So, they wait. In Pakistan, repeated political surprises and policy swings have led companies to focus on short-term survival rather than investing in long-term capacity and R&D. This aligns with findings from larger studies: uncertainty deters investment in future production capacity.

These similarities are important because they reveal a common mistake in policy discussions: treating policy uncertainty as a small, local, or short-lived problem. It's not. It's a broad problem that affects all decision-making. When regulatory results are harder to guess, companies both at home and abroad would rather wait and see what happens. That's not an irrational choice. It's a normal reaction to a situation where the rules can be changed. The problem worsens when financial markets are weak or when borrowing costs jump quickly in response to political events. Simply put: uncertainty hurts more when there's less of a safety net. That's why the same weakness appears in different places—from Santiago to Karachi to U.S. manufacturing—whenever policy becomes unclear.

How delayed decisions become structural drag

One project being put off might not be a big deal, but lots of projects being put off are. When companies keep delaying spending, the amount they can produce goes down. People don't get hired. Training and innovation get put on hold. This turns a short-term drop in demand into a permanent loss of production potential. An analysis of the euro area that used models to look at what would happen if policy uncertainty returned to pre-pandemic levels found that investment is especially sensitive: if uncertainty went down in a lasting way, investment growth could rise by about 2.8 percentage points in some situations, while if uncertainty went up, investment would drop much more than consumption. These aren't small changes; they add up to slower overall growth. It’s simple: uncertainty makes it harder to start investments that can't be undone, so companies wait, which, overall, lowers the amount of capital created and the amount we produce in the future.

Financial problems make the drag worse and faster. High policy uncertainty tends to raise borrowing costs. Lenders want more money for holding assets that are affected by unclear policies. Stock markets expect worse policy outcomes, which lower stock prices and make stock-financed investment harder. Currency swings can greatly increase borrowing costs for companies that owe money in other currencies, raising the expected cost of projects that rely on imported equipment or stable exchange rates. In the U.S., models show that a one-standard-deviation increase in policy uncertainty can lower GDP growth and employment by about 1 percentage point over 6 to 8 quarters, and larger shocks cause much larger problems. That action—quick financial changes followed by slow changes in the real economy—is what turns hesitation into lasting damage.

Policy uncertainty also affects education and skills. Companies that delay spending also often delay training their workers. Training budgets get cut or put off. When schools and training programs depend on businesses for help or funding, less corporate investment hurts those programs. This is how uncertainty affects training: fewer apprenticeships, less on-the-job training, and less demand from businesses for the skills that schools provide. The result is a mismatch between the skills people have and the skills companies need, and a slower spread of new technologies that increase output—both of which contribute to lasting output loss. The cause is direct enough that clear policies should be seen as a key part of building skills.

What should educators and policymakers do about the cost of policy uncertainty? If uncertainty acts like a hidden tax on future growth, we need to do two things: reduce the uncertainty we can avoid and build stronger defenses against the shocks we can't. For policymakers, the first step is to promise clear, rule-based policymaking whenever possible. That includes clearer schedules for laws, advance-notice review processes, and stable paths for changing regulations in major industries. Central banks and government leaders should carefully communicate their plans. Estimates for Europe show that lowering policy uncertainty back to pre-pandemic levels would raise GDP by about 1.2% and raise investment more than consumption. Those are big benefits for making things more predictable. Smaller changes in purchasing rules, how capital is taxed, and how grants are awarded can have big effects by reducing the specific concerns that make investors nervous.s.

Leaders in education need to turn general policy clarity into real-world practices. School and university leaders should plan for three time frames: maintaining stability now, keeping programs running in the medium term, and aligning with the job market's needs in the long term. Steps include budgeting for training programs over several years, including contract clauses that protect course continuity when funding changes, and partnering with employer groups rather than single sponsors. When public funding is unstable, schools should find alternative sources of income and work with regional groups to soften the effects of shocks. These efforts make investments in skills less dependent on each political cycle and help protect the technical ability that the economy needs to recover. The goal isn't to protect schools from politics; it's to lower the cost of political changes so that one election or regulatory change doesn't ruin training for a generation.

Lastly, for companies and investors, the policy is clear: consider policy risk when making decisions and protect against risk whenever possible. That includes using contracts with clauses that adjust for regulatory changes, using multiple suppliers to avoid being too exposed to single policy situations, and keeping cash on hand to allow projects to continue through short-term problems. Government programs that encourage investment should reward commitments that last through normal political cycles, such as multi-year grants and tax credits tied to results rather than promises and guarantees that lower the risk of long-term investments. The findings from Pakistan and Latin America show that policy clarity matters on a small scale: when business planners can see a likely policy path, they commit; when they can't, they wait.

Treat predictability as policy

We started with a simple idea: spikes in policy uncertainty aren't just interesting to academics. They have real costs. A sudden shock to uncertainty in 2025 looked like a big deal, and models show it would hurt growth and employment. Across Latin America, Pakistan, and Europe, the same pattern emerges: financial problems arise immediately, and investment and education suffer later. This is the high cost of policy uncertainty. The policy lesson is just as clear. Being able to predict the future isn't just a nice-to-have for officials. It's a way to help with growth. Governments should use clear, rule-based processes and stable procedures for changing major regulations. Education leaders need to strengthen continuity plans and explore alternative funding sources and business partnerships. Companies should consider policy risk and take steps to protect against it. Doing these things makes waiting less appealing. It turns projects that are on hold into real capacity and delayed training into timely skills. The result is higher investment, stronger job markets, and steadier growth. Think of predictability as a policy tool and act so that future decisions don't have to wait for today's politics.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Aguilar, A., Guerra, R., Müller, C., & Tombini, A. (2026). The macro-financial impact of economic policy uncertainty in Latin America. BIS Working Papers No 1324. Bank for International Settlements.

Baker, S. R., Bloom, N., & Davis, S. J. (2016). Measuring Economic Policy Uncertainty. The Quarterly Journal of Economics. (Referenced in EU analysis.)

European Commission. (2024, November 15). The cost of uncertainty – new estimates. Autumn 2024 Economic Forecast: A gradual rebound in an adverse environment. Directorate-General for Economic and Financial Affairs.

Hussain, S. (2023). Economic Policy Uncertainty and Firm Value: Impact on the Pakistan Stock Exchange. Sustainability. (Firm-level evidence on Pakistan and investment responses).

Kliesen, K. L. (2025, April 7). Uncertainty Shocks Can Trigger Recessionary Conditions. St. Louis Fed, On the Economy blog. (EPU shock magnitudes and nonlinear GDP effects.)

Comment