The great unspoken rate shock: why “silent tightening” was never silent

Input

Modified

Silent tightening was not silent — it reshaped global credit through hidden market channels Geopolitical shocks shifted capital from venture funding to private credit, slowing growth The real policy failure is ignoring how financial plumbing redirects risk

In 2022, inflation, sanctions, and disruptions in supplies didn't just appear – they hit us hard. The policy discussion called the aftereffects silent tightening, describing shifts in balance sheets, higher term premiums, and banks cutting back on lending without the central bank officially raising rates. This description is too simple. When Russia drastically raised its policy rate to double digits, keeping it there for several years, it wasn't a minor adjustment. It was a forceful move that changed the movement of money across borders, the amount of money banks had in reserve, and how willing people were to take risks.

At the same time, venture capital disappeared from many markets, and private credit strategies grew as investors looked for returns while avoiding the ups and downs of public markets. This led to a big change in how credit was priced, which acted like traditional tightening. The difference was that it was unevenly distributed, not easily seen, and focused on the very parts of the system that support new ideas and growth. This article argues that calling it silent is wrong. The shock was clear to markets and companies; the problem was that it wasn't well explained to the public. The lesson for policymakers is clear: If tightening can hide in certain parts of the market, they need to change how they understand financial signs and who is affected by them.

Silent Tightening: A Systemic Shock Misunderstood

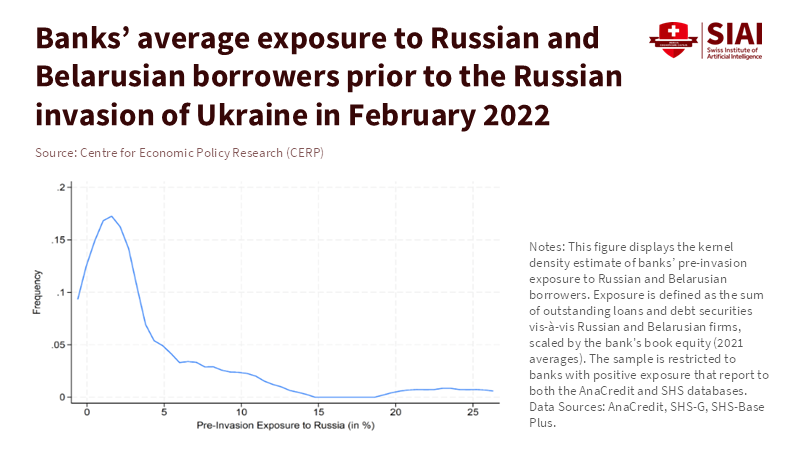

The term silent tightening suggests a small, gradual decrease in available money that regulators could handle privately. This understanding doesn't match what has actually happened over the past three years. In Russia, the main policy rate rose into the teens and briefly reached almost 21% before falling a bit. These aren't small changes; they're significant, volatile levels that directly affect international trade financing, relationships between banks in different countries, and how risk is assessed across Europe. The spikes in domestic rates changed the incentives for both local banks and their global partners, leading them to move credit away from riskier, long-term investments and toward short-term, higher-yield options. This wasn't just a Russian issue. It changed asset yields and liquidity premiums in European markets that were connected to Moscow through trade and investment.

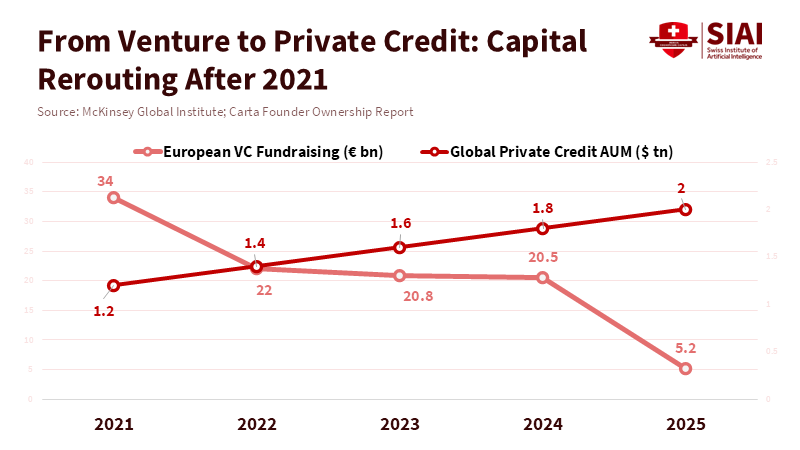

We can see this shift if we look beyond central banks' headlines. Venture capital, a key driver of growth for new businesses, experienced a decline for several years. The number of active venture capital investors and the number of deals they were doing decreased sharply after reaching highs in 2021, especially in Europe, where foreign investors pulled back. Companies that had depended on selling their stakes in later stages found those options were no longer available. Simultaneously, private credit options expanded. Institutional investors put money into direct lending and structured private credit as yields increased and risk premiums in public markets spiked. This wasn't by chance; it was a logical investor response to higher policy rates, stricter bank lending rules, and an uncertain future. The end result is like traditional monetary tightening – less risk-taking and slower credit for innovative companies – but it happened through market changes instead of a single policy announcement.

This pattern is important because silent tightening concentrates the pain and slows down recovery. Unlike a general rate increase that affects all consumption and investment equally, this kind of fragmentation moves financing away from sectors that need long-term or non-bank funding. These include high-tech research and development, scaling-up manufacturing, international service companies, and parts of the green transition. These sectors rely on long timeframes and easy ways to exit investments. When capital moves into private credit and defensive strategies, it replaces growth capital with loans that have to be paid back regularly and have strict conditions. Innovation continues, but it happens more slowly, more cautiously, with less potential for major gains, which harms the public interest – jobs, the spread of new technologies, and increased productivity.

How Geopolitics Changed Risk Pricing and Capital Flows

Geopolitical shocks exacerbated weaknesses in Europe's financial system. Initial supply shocks in energy and other materials caused inflation to rise. But the monetary responses that followed, including aggressive rate settings in some areas and uneven effects across borders, created secondary problems that are the real story for companies and banks. Higher rates outside the euro area, and risk-based adjustments within it, made some interbank lines more expensive or simply unavailable. This forced banks to shorten the terms of their loans, save more cash, and re-evaluate the cost of corporate credit. For borrowers who were already struggling, this cut off their lines of credit and caused capital to move into private credit formats that demanded faster cash returns or stricter conditions. These changes can be seen in fundraising data and in the increased amount of private debt assets being managed worldwide.

To understand how this works, consider an investor who used to fund a growth-stage round. With public valuations down and fewer opportunities to exit investments, the investor now has two bad options: hold onto old investments with uncertain returns or invest in private credit that provides regular cash flows and shorter, contractually predictable payouts. The economics favor strategies that protect capital and deliver short-term yield. This explains both the decrease in the number of active venture capital firms and the increase in private debt fundraising totals. In short, the same event that caused inflation also redirected the marginal dollar of global investment from equity-style risk to contractual credit.

This redirection is not equal. Europe's government and corporate balance sheets had high debt levels before the shock. Government debt in the euro area remained high, limiting the ability to absorb shocks. When fiscal space is limited, a decrease in private financing quickly translates into real economic problems. High debt burdens mean governments can't offset private cutbacks without long-term costs, so the repricing of private markets results in prolonged output loss rather than a quick, short-lived adjustment. The fiscal situation turns market fragmentation into a source of ongoing stagnation risk.

Changes for Educators, Administrators, and Policymakers

First, we need to monitor more broadly. Traditional indicators like headline policy rates, CPI, and interbank spreads are necessary but not enough. Regulators need system-wide dashboards that capture fundamental flows: venture financing volumes, private-credit assets under management, covenant tightness, cross-border correspondent exposures, and credit migrations across sectors. These are the channels that transform silent tightening into real economic pressure. Without them, authorities will misunderstand a tightening episode as minor or isolated when it is actually deep and systemic. Public agencies should require more transparency for large private-credit funds and require aggregated reporting of non-bank lending into critical sectors.

Second, fiscal policy needs to be smarter about how it channels funds. When private equity decreases and private credit increases, governments shouldn't try to outbid private lenders on coupons. Instead, they should design contingent instruments like revenue-based financing, matched public warrants, or targeted, time-limited guarantees that restore risk-bearing capacity without replacing private-sector discipline. For education and research institutions that are the source of innovation, this means creating bridge facilities and convertible support that maintains managerial autonomy while reducing the cost of scaling. Public investment should be catalytic, not paternal, and structured to attract patient capital during market stress. Evidence shows that when public instruments are well-targeted and time-bound, they prevent lasting damage without creating long-term dependency.

Third, central banks and supervisors need to treat fragmentation as a major macro-financial risk. This requires coordinated tools such as swap lines, targeted liquidity facilities, and explicit guidance on how national rate differences affect cross-border credit. Central banks should also broaden stress-test scenarios to include long-term shifts in funding composition rather than just level shocks to rates. Stress tests that assume capital simply bounces back after a rate shock don't reflect the reality that funding composition can change permanently if investor preferences and fund-structuring incentives adjust in response to extended uncertainty. Supervisors should therefore incorporate scenarios where equity-style risk capital shrinks and contractual credit grows, and measure the consequences for lending to innovation-intensive firms.

Being prepared for common criticisms can help improve this program. One likely argument is that private credit provides valuable financing and that growth shouldn't be protected from market forces. This is true. The goal isn't to block private-credit growth but to make its expansion visible and its macro consequences manageable. Another criticism will emphasize fiscal responsibility, arguing that governments don't have the resources for new guarantees. The response is that catalytic, temporary instruments can be designed with strict sunset clauses and loss-sharing rules. These instruments are less expensive than the long-term costs of lost businesses, missed technological advances, and persistent unemployment. Finally, some will argue that geopolitics is beyond policy control, which is partly true. However, policy can control how transparently and evenly the costs of geopolitical shocks are distributed. Transparency and pre-committed backstops reduce contagion and spread risk in a way that preserves dynamic sectors.

Turn the Whisper into Public Policy

The term silent tightening was more misleading than accurate. The shock that began with supply disruptions and sanctions has had clear effects: soaring rates in some areas, a decline in venture capital, a boom in private credit, and rising sovereign debt burdens. These outcomes won't disappear once the war ends; they will shape recovery paths for years to come. The correct response isn't to long for low rates but to change institutional practices. We need to monitor private-market flows more broadly, adopt fiscal instruments that encourage patient capital without creating moral hazards, and retool central-bank stress tests to capture shifts in funding composition. These changes won't be easy, but they are achievable. If policymakers address fragmentation as a data and design problem rather than as an inevitability, they can turn market repricing from a source of long-term stagnation into an opportunity to rebuild a more resilient and inclusive financial system. The silence was never the problem; the failure to pay attention was.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position of the Swiss Institute of Artificial Intelligence (SIAI) or its affiliates.

References

Bank of Russia. (2026). Key Rate. Bank of Russia press releases and official data.

European Central Bank. (2025). Economic Bulletin.

Eurostat. (2025). Government finance statistics; general government gross debt.

PitchBook. (2024–2025). European venture reports and data on active VC counts and deal volumes.

Preqin / RBA / IMF analyses (2023–2024). Private credit growth and assets under management.

Comment